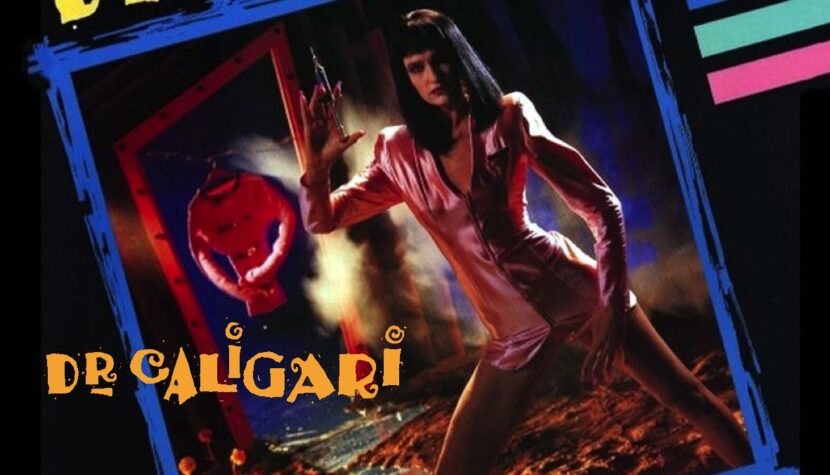

DR. CALIGARI. Psychodelic, expressionistic sci-fi horror

Dubbed (somewhat exaggeratively) as pornographic, it’s more about an obsession with sexuality than actually showing it. Everything is presented in makeshift, yet incredibly imaginative sets. The convention of B-movies meets pre-war horror and takes it to a pastel cabinet of oddities straight from the 1980s.

Stephen Sayadian’s 1989 film has elements of both a sequel and a new version of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but ultimately it’s just a lighthearted variation on the theme. Here, the titular character is… a woman (Madeleine Reynal), the granddaughter of the original Caligari. She runs the Caligari Insane Asylum (C.I.A.), a facility for the insane, where she continues the family tradition in her own way.

The patients in the facility are subjected to electroshock therapy and dangerous experiments. Dr. Caligari psychologically abuses them during therapy sessions and also tries to combine the traits of cannibals and nymphomaniacs. All this is in an attempt to find a way to transfer the preserved brain of the original Caligari into the body of Dr. Caligari. However, before this can happen, another patient arrives at her institution – Eleanor Van Houten (Laura Albert). The woman is a nymphomaniac with nightmares and suggestive hallucinations. Consequently, she can’t distinguish reality from fiction. Her concerned husband, Lester (Gene Zerna), arranges a visit to Dr. Caligari and decides to place his wife in her insane asylum. The course and consequences of therapy will turn out to be surprising for everyone.

The entire film was shot in a studio, and the set design is as artificial as possible. Almost all the rooms in Dr. Caligari’s facility don’t even have walls, and if they do, they are part of the set. Most often, the background is a black, undefined space contrasting with the flashy colors of the doors and furniture. Their asymmetrical shapes are reminiscent – not coincidentally – of German expressionism, of which the most famous representative in cinema is indeed The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari from 1920. There, the entire depicted world was distorted because it was the vision of a madman.

In the 1989 film, expressionist mannerisms were borrowed to set up the interior of the insane asylum. Distorted doors to the patients’ cells, furniture in the doctor’s office, or decorations in the background – the entire set design is dominated by geometric shapes and sharp edges. It’s not black and white (like in the pre-war film) but vivid and colorful. And such a combination is surprisingly successful, especially when combined with pastel, pink, and yellow costumes stylized as medical attire, appropriate for the patients and staff of the insane asylum.

Like a monster stitched together from completely different genres, Dr. Caligari surprisingly presents itself cohesively. One can quickly get used to the flashy style and evidently exaggerated acting (stylized to mimic silent film acting); this artificiality even has its charm, especially after all these years. Dr. Caligari is primarily about form, and the story isn’t the most important aspect here, but the events presented more or less come together. Interestingly, the film can be successfully interpreted as a satire on a society fixated on sex. A blunt, almost prophetic commentary on today’s state of affairs is a scene where the nymphomaniac protagonist masturbates in front of the television, with the screen showing open female lips and a waving tongue. Even David Cronenberg himself wouldn’t be ashamed of it.