DON’T LOOK NOW. A masterful horror movie and truly terrifying experience

The feeling of engaging with a remarkable work that captivates from the very first minutes is undoubtedly a rare experience, especially for a horror film. But in the case of this adaptation of Daphne Du Maurier’s prose, there is something more.

While I can savor Roeg’s directorial artistry, his bold choices in narration and editing, the closer to the finale of Don’t Look Now, the more significant fear engulfs me. I know only too well what awaits at the end of this journey – the revelation experienced by the main character, and with it, ourselves. It’s not a moment of excitement or catharsis. Instead, it’s an example of helplessness. Not just the moment of unveiling the mystery but the way expectations are confronted with the relentless reality.

After the unexpected death of their young daughter, John and Laura Baxter leave rainy England for the equally gloomy city of Venice. John oversees the restoration of a church, while his wife tries to recover from the tragedy. By chance, they encounter two Scottish tourists, sisters, one of whom is blind and possesses mediumistic abilities. She claims to have seen their deceased daughter, happy and smiling, which rekindles hope and the will to live in Laura. John, on the other hand, is less convinced and suspects some foul play from the women. However, they soon inform him that he, too, has supernatural abilities, and to make matters worse, he is in mortal danger if he remains in Venice.

Don’t Look Now is based on a story by Du Maurier, whose works were previously adapted by Alfred Hitchcock in films like Rebecca (1940) and The Birds (1963). Comparing the two directors, it’s challenging to find more contrasting styles – Hitchcock’s classical approach to storytelling and masterful suspense building contrasts with Roeg’s loose narrative structure. With Hitchcock, the psychology of characters and meticulously crafted sequences leading to a climax serve to generate tension. With Roeg, specific stylistic choices, a strong emphasis on each shot, sound, and editing, determine how we perceive the story and its characters.

Horror lies precisely in the interplay between what we see, the successive images forming an unsettling mosaic of doubt and dread, and the interpretation of events, understanding the author’s discourse.

The same holds true in Roeg’s later film, Bad Timing (1980), which is by no means a sci-fi or horror movie but equally terrifying, offering a brutal dissection of human desire. In both cases, the climax leads to a shocking revelation that prompts us to reconsider the meaning and course of the entire narrative.

Returning to Du Maurier’s original story, Roeg takes only the basic plot, shedding the exceptionally unsympathetic characterization of John and the highly ironic tone. The meaning of the title of Don’t Look Now is left open to the viewer’s interpretation. What Roeg infuses into his film, however, transforms this simple narrative into a genuinely moving impression where the difficult-to-define fear of the unknown and the sense of loss are redefined.

The foundation for this redefinition is laid in the very first scene of Don’t Look Now, an absent element in Du Maurier’s book: the description of the Baxter’s daughter’s death. Instead, Roeg presents signals foreshadowing the tragedy. As John reviews slides of a church at home, he comes across one that features the silhouette of someone in a red raincoat similar to what his daughter is wearing as she plays near the pond. When he accidentally spills water on the slide, he witnesses something peculiar: the figure in the photo starts to bleed, and a stain of blood gradually covers, even destroys the rest of the image. Shortly after, John hastily rushes out of the house towards the pond, as if sensing that something terrible has happened. He retrieves his daughter’s lifeless body from the water, attempts to resuscitate her, but to no avail. The drama of the helpless father overshadows what the director had revealed a few seconds earlier – John’s ability to foresee the death of his little Christine.

But were we really witnessing that? The protagonist of Don’t Look Now doesn’t later dwell on these strange omens, and he responds to the sisters’ explanation that he’s clairvoyant in a mocking way, making it clear how he feels about mystical matters. Surprisingly, we have no trouble accepting his point of view, not just because Donald Sutherland, who plays John, successfully combines cold rationalism and authoritative demeanor with the warmth and concerns of a man who wants to shield himself and his wife from further pain. His reluctance towards the sisters doesn’t solely stem from disbelief in the supernatural but appears to be more rooted in his conviction that they want to exploit the Baxter’s personal tragedy for their own purposes.

Roeg is keen on making the viewer’s perspective align with John’s, cleverly manipulating our judgment of the two elderly women. In their first meeting with Laura, the camera films not only these characters but also numerous mirrored reflections of the women, implying the ambiguity of the whole situation. The emotional intensity of the moment when John’s wife finds out that one of the sisters saw Christine is suppressed by the detached approach of the other woman, who coldly explains her sister’s mediumistic abilities to Laura. How can we explain the scene of both elderly women’s hysterical laughter, completely unrelated to any other part of the film? Is it just a projection in John’s mind, interpreting the seemingly harmless-looking women in this manner, or is it an authentic depiction of their true nature? But then again, is there anything inherently wrong with the laughter itself?

The setting of Don’t Look Now, Venice, becomes the ideal location for extraordinary and ominous events. The submerged city, serving as a tourist attraction, appears here as a labyrinth, not only due to its numerous canals and bridges connecting alleyways where it’s easy to get lost. Roeg doesn’t resort to the motif of the foreigner who doesn’t speak the language – John speaks Italian fairly well, but there’s still a barrier in his interactions with the Venetians, regardless of whether it’s the cardinal collaborating on the church’s renovation, the police inspector he turns to for help, or random inhabitants.

Yet the idea of a labyrinth is further associated with the director’s style, composing seemingly disparate frames, interweaving temporally distant and often contrasting moments (the iconic love scene between Sutherland and Christie is juxtaposed with scenes of their characters getting ready to leave the hotel). He doesn’t make it easy for the viewer to find a straightforward definition for what they’re watching. Roeg has every right to experiment with the ambiguity of the film’s initial situation, placing it within the horror genre but deliberately avoiding typical genre resolutions and effects.

Regardless of whether the characters are genuinely caught in supernatural events or not, the whole sense of the uncanny presents itself as something very earthbound, though non-specific.

It’s no wonder that John cannot find a balance between his rationalism and the successive signals undermining this order. Although he possesses all the elements enabling him to make an accurate judgment of the situation, he unwittingly steers toward another tragedy, or perhaps the same one all over again.

From the description above, one might conclude that Don’t Look Now is a film whose success depends entirely on Roeg, which is somewhat misleading. The actors also perfectly fit the atmosphere of looming uncertainty and the drama of people trying to forget their misfortune. I’ve already mentioned Sutherland, and Julie Christie is captivating not only with her ethereal beauty. There are moments when her character, Laura, appears absent, seemingly participating in the conversation but in reality still mentally returning to her daughter’s death. The sadness on the actress’s face conveys more than Du Maurier’s description of her character in the short story, contrasting with Sutherland’s peculiar features (those slightly bulging eyes, curly hair, mustache, and towering stature). The debut film score by Pino Donaggio enchants with romantic compositions that bring to mind his later collaboration with Brian De Palma, while Anthony B. Richmond’s BAFTA-winning cinematography does justice to Venice, portraying it as a city of great beauty but also a place impenetrable and menacing. Setting the story in the off-season makes it look like a faded postcard in the cold daylight. Only red seems to be the lone vibrant color, and at the same time, one that has little to do with life.

Lastly, I need to write a few words about the fear that Don’t Look Now evokes in me during every viewing.

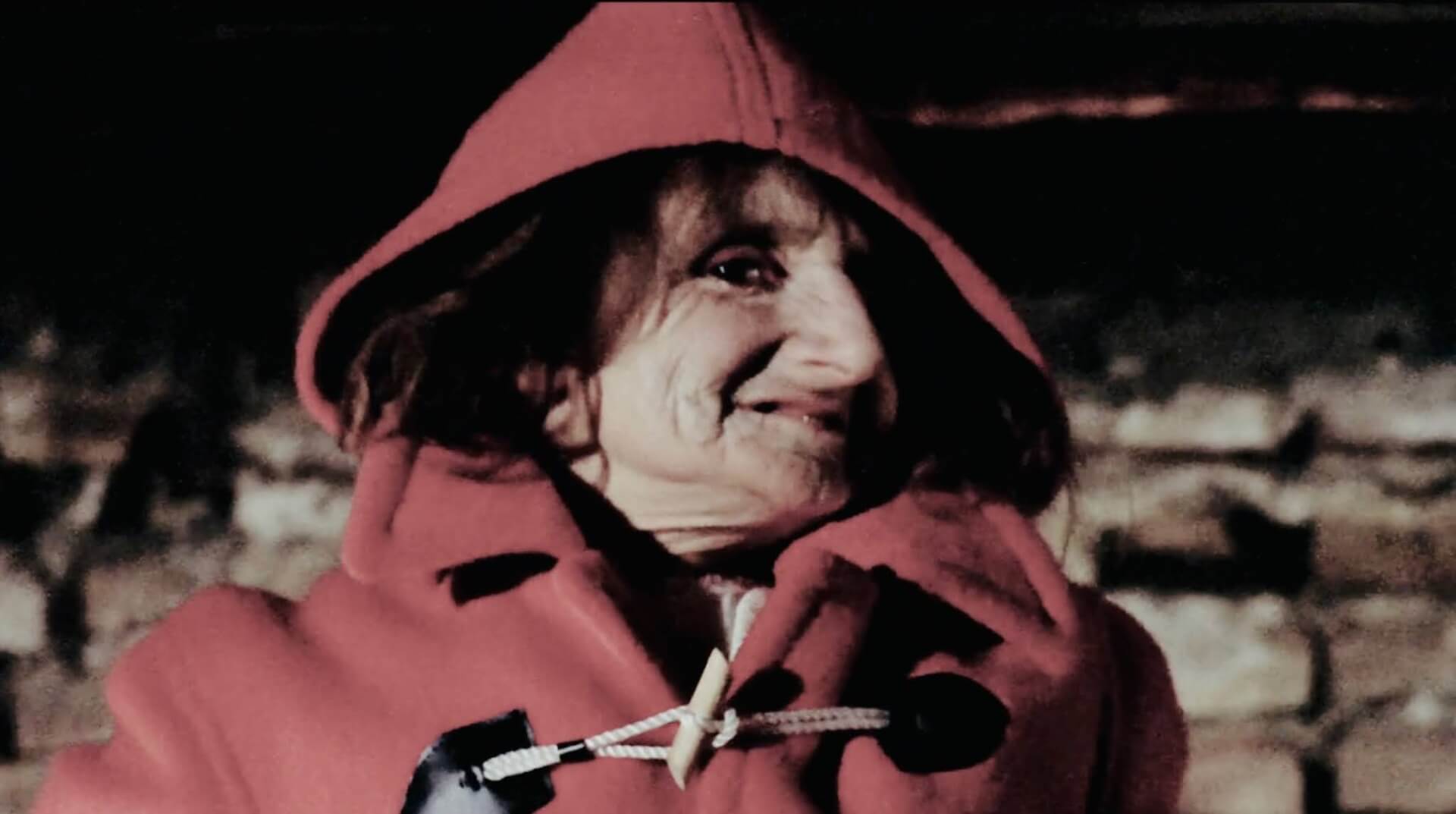

I don’t want to do it because I have to recall the final scene – John Baxter chases a figure that he perhaps already considers the specter of his deceased daughter. When she turns toward the camera, terror takes hold of me, although the memory of the first viewing prompts me to be somewhat more specific about the state in which the ending left me. It was paralysis, a sudden shock that passed through my body, destroyed my defenses, and reached me unexpectedly. On the one hand, it’s related to the unpredictability and grotesqueness of the image; on the other hand, it’s connected to a cosmic injustice and a logic so cold and relentless that it borders on particularly bitter irony. But Roeg doesn’t want us to laugh or terrify us in the typical manner of horror creators. Instead, he leaves us in a state close to catatonia, from which we emerge with great difficulty. Until the next screening.