ASTEROID CITY. Wes Anderson’s intriguing philosophical journey

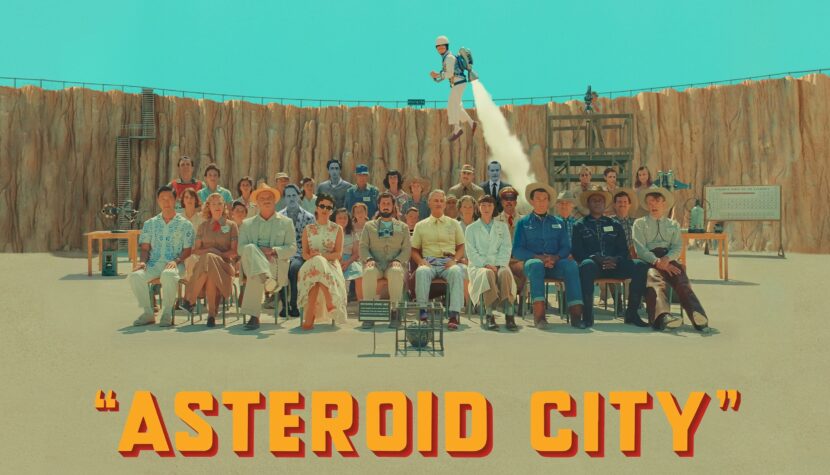

Wes Anderson is currently at perhaps the most intriguing moment of his career, one in which, after years of steadily building his reputation, he seems to be slowly saturating the wider audience. Each new announced project competes with one another in terms of the number of big-name actors involved in its production (in the case of Asteroid City, they barely fit on the poster). The symmetry of frames has not only become the director’s trademark but an aesthetic decision automatically associated with him. The pastel color palette floods the Instagram accounts of teenagers enamored with the scenic beauty of emotional burnout. On the other hand, the consistently developed style is beginning to make viewers squirm in their seats; the first accusations of the director closing himself off in a loop of repetition and selling out his ambitious soul for the sake of production are starting to surface.

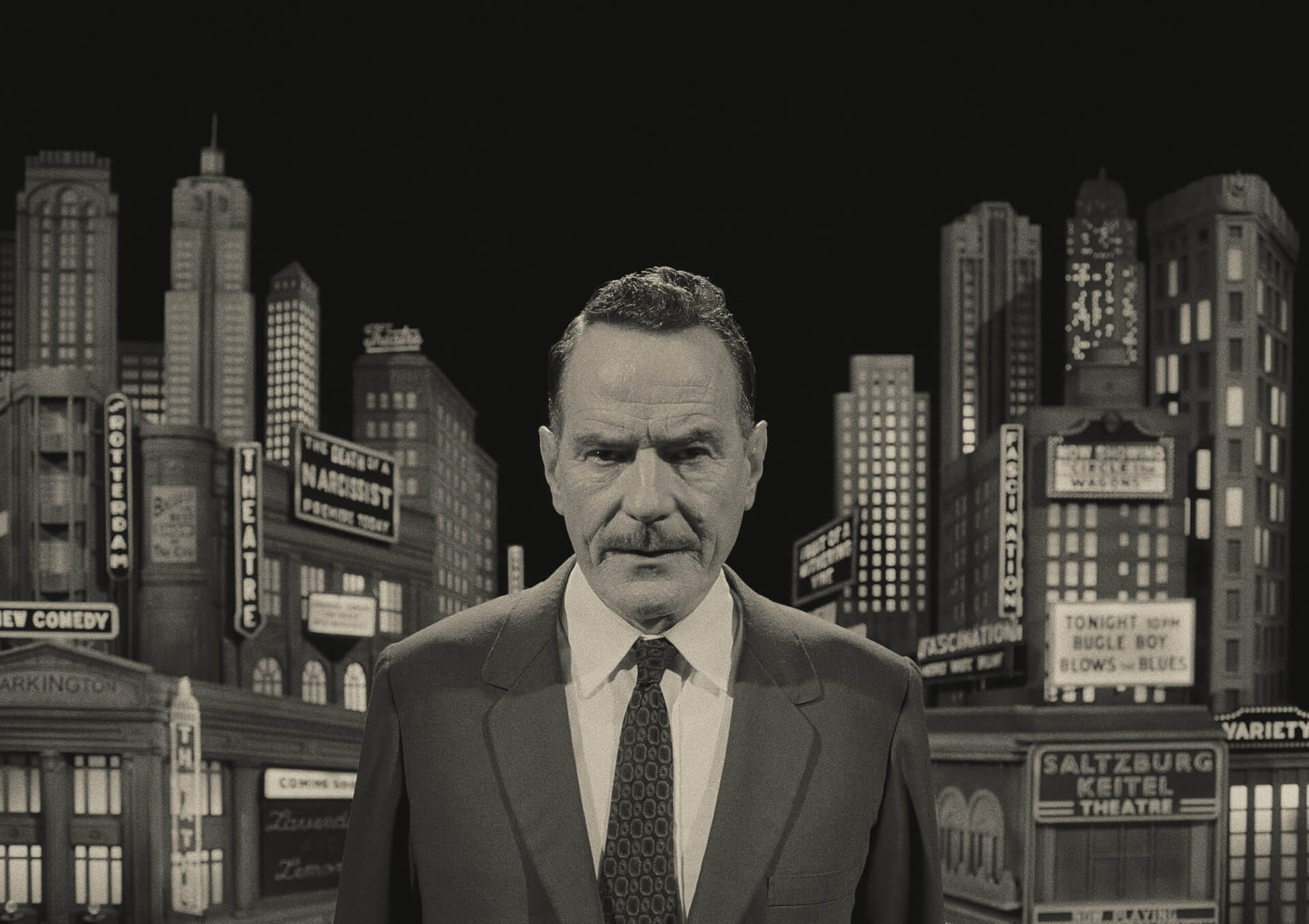

However, French Dispatch brought a thematic breakthrough. Anderson’s characteristic creation of a world finally became a pretext for what had subconsciously interested the creator all along – the beauty of storytelling, even more important than the story itself. In a film from two years ago, the camera entered the viewer’s imagination, transferring impressions of readers onto the film; adapting not the text of the columns themselves but the experiences, projected by our brain, into moving images that appear to us somewhere under the dome while browsing through journalistic texts. Asteroid City will deepen this newfound love for narrative matter. The TV presenter in a tight black and white frame will announce the upcoming performance. The actor will step out of character, the scene will be cut, and the director will share with us his production doubts. The fundamental tale of the cosmic nature of “life in a moment” will be preceded by a visual division into acts and scenes borrowed from dramatic text in the form of static panels. The script’s “what” will become the consequence of the director’s “how.”

This doesn’t mean, by any means, that the plot has become secondary for Anderson; it rather appears as a direct consequence of the complexity of the depicted world. The titular Asteroid City is a red cardboard wasteland, within which there is a row of automatons, an auto repair shop, a run-down hostel, and a research station. Everything is surrounded by a sandy nothingness stretching to the horizon. We get to know a group of characters by chance on their journey; most either live in the imaginary “town” or bring their children there for the annual prestigious science competition. Among the newcomers: a jaded film star (Scarlett Johansson), a widower (Jason Schwartzman) hiding his late wife’s ashes in a blue Tupperware box from his children, and his emotionally distant father-in-law (Tom Hanks). Among the more or less temporary residents: an eccentric hostel and everything-automaton owner (Steve Carell), an unfulfilled director of the research center (Tilda Swinton), and a military battalion commander (Jeffrey Wright) stationed in the town, who oscillates between soldierly dryness and a romantic nature. Each with their own micro-story of unfulfilled life; each with an emotional scar covering the remnants of their distinctive personality. Within the desert plain of Asteroid City, every unique eccentric is paradoxically similar to one another; the same microscopic gymnastics of resigned faces, the same vacant gaze scrutinizing their exhausted souls.

From this spiritual kinship, Anderson derives the motivation to build relationships, to briefly participate in the solitude of life. The actress will engage in an ambiguous romance with the widower, his son, a promising genius, will finally find understanding among a group of equally promising geniuses. Asteroid City, forced by the course of the story into a pandemic-familiar isolation, will undergo an unexpected stop on the way. Both the actual journey, conducted from an unclear point A to an even less clear point B, and metaphorically, a broader, life-related journey. The hostel in the middle of the wasteland will become a starting point for human existence, consumed by the rush to erase manifestations of self-reflection. Finally, there will be a moment to breathe, to have conversations that have not been had before, to speak about perpetually unspoken topics, and sometimes even those never realized, determining the lives of this pastel-clad group of eccentrics.

Everything in this reinterpreted company of livelier than usual scientific equations and formulas. “Gravity is probably my favorite law of physics,” one of the young geniuses will say at some point, and it seems like it’s not just him. The attraction of Earth – body also functions in the orbit of body – body when solitary atoms with various histories and bizarre physiognomies begin to gravitate towards the Other in their emotional alienation. Contact becomes a priority; both to understand the Other and more often, to finally expose oneself to the world. In this context, even a somewhat bewildered extraterrestrial landing on Earth for a moment will immediately get lost in the complexity of human interpersonal physics. Anderson’s “Other” is both an inaccessible, silent judge and, in its stoicism, a perfect listener, a receiver of others’ textures of worries. Therefore, all meetings on the red desert will be important primarily on an individual, introspective level. This also translates into the peculiar space of Asteroid City; simultaneously divided into distinct acts by narrative time, and in its essence, somewhat timeless. Attempts to build relationships will never move forward. The same absurd police chase of a car adorned with a fiery body will drive through the city streets three times. The California quail will always search for insects in the same clump of grass.

Allow me, dear reader, to explain myself. Writing about Asteroid City using imperfect verbs is not just a rhetorical flourish – it’s simply challenging to do it differently. Wes Anderson constructs a narrative reality based on a world that is still waiting for something, a world counting down the days to the ultimate escape from itself. In the end; a world hoping for a final metaphysical transformation, covering the conventionality of reality, revealing the truth hidden behind the cardboard rock or plastic façade. Of course, none of this will ever happen. But the existential curiosity about what lies beneath the colored paper with the Pantel logo is perhaps the most intriguing philosophical inquiry that Anderson has ever embarked upon.