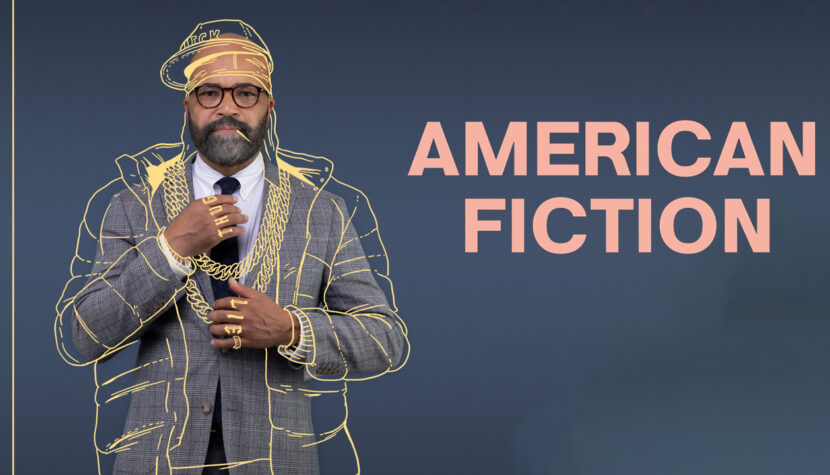

AMERICAN FICTION. Why “Green Book” should never have won an Oscar [REVIEW]

We meet Thelonious “Monk” Ellison at a rather unfortunate moment. Due to regular disputes with students, the protagonist is sent on an unpaid “academic leave”. As if that weren’t enough, his latest novel – a contemporary version of Aeschylus’ Persians – can’t find a publisher (wonder why?). Things aren’t any better in his personal life: his mother begins to show the first signs of Alzheimer’s, his sister, who held the family together, dies, and his brother, with the mentality of a liberated teenager, embarks on an exhibitionistic odyssey after his wife catches him in bed with his lover. Monk (the pseudonym presumably derived from the surname of the famous jazz musician Thelonious Monk) vents his accumulated frustration in the only way he knows how: through his pen. Furiously striking the keys of his laptop, he creates a parody of black literature – a stereotypical tale of life in the ghetto, ending with the obligatory death of the main character at the hands of a white policeman.

Based on Percival Everett’s book, “American Fiction” is primarily a satire of the American publishing market. It’s sharp, merciless, and, most importantly, humorous. Many groups are targeted here, but primarily white, liberal publishers and populist black authors. The former publish the latter’s novels to alleviate the guilt stemming from the times of slavery. The latter write to meet the needs of the former – to catch up with current trends dictated by – surprisingly – white readers. It’s a perpetual cycle, driven by guilt and market demand. Monk desperately tries to swim against the current by creating novels featuring black intellectuals breaking away from ghetto stereotypes, much like James Baldwin did in the past. However, his efforts are doomed to fail – Americans simply don’t want to read something like that. Monk’s parody, titled “My Pafology” (later renamed to “Fuck”), becomes a middle finger aimed at the entire publishing-reading process. The problem is, the market takes the book completely seriously, and it instantly becomes a bestseller, nominated for major literary awards – no one sees the camouflaged irony. By declaring war on the system, the protagonist is inadvertently absorbed by it.

In perhaps the best scene of the film, Monk engages in a philosophical discussion with Sintara Golden, the author of popular novels set in the black underworld. “Aren’t you tired of it? Black victims? Black rappers? Black slaves? Blacks killed by police? All those pathetic narratives about black people in tragic life situations who manage to retain shreds of dignity before death? I’m not saying such situations don’t happen, but aren’t we something more?” Monk’s problem, which he narrates, seems even more evident in cinema. Just look at the Oscars – what films with black protagonists can count on recognition by Academy members? Let’s just look at examples from the last decade or so: “Mudbound”, “12 Years a Slave”, “Hidden Figures”, “The Help”, “Green Book”, and the short film “Two Distant Strangers”. Regardless of their varying quality, what do these films have in common? “The white savior trope.” Only “Django Unchained” and “Get Out” break this pattern with postmodern irony, and “Moonlight”, where the main theme is identity, features solely black characters.

If this type of cinema is appreciated, it’s always at the expense of others, often more valuable positions. A scandalous situation occurred in 2019 when the Oscar for Best Picture went to the creators of “Green Book”. Spike Lee and Jordan Peele, present at the ceremony, didn’t hide their bitterness about this decision, openly refusing to clap. Indeed, narratively speaking, “Green Book” was a huge step backward concerning representations of black people. A film made by white filmmakers, replicating the “white savior” pattern, consulted only with the family of the white protagonist (Nick Vallelonga, son of the character played by Viggo Mortensen, served as a producer on set) – no one bothered to contact Dr. Donald Shirley’s relatives before starting the filming. So, an anti-racist film with racist roots won the Oscar – satisfying the American audience’s demand for mainstream social cinema. It’s against this kind of art that the main character of “American Fiction” protests. The triumph of the Farrellys’ work is even more painful, especially considering that “Black Panther” was also nominated that year, a film of much higher quality, directed by a black filmmaker, addressing a similar, albeit more complex, topic.

Returning to Jefferson’s debut film: precise, thought-provoking (as you’ve probably noticed by now) satire intertwines with a rather clichéd family plotline. It’s a strange combination, giving the viewer a schizophrenic feeling of watching two different movies at once. While Jefferson is ruthless and tactless in portraying the intricacies of the publishing market, he suddenly becomes sensitive and understanding in Monk’s personal scenes. “American Fiction” then transforms into a crowd-pleasing tale of a fractured family coming together, and it becomes quite clear why the film won the Audience Award at the Toronto Film Festival last year (five years earlier, “Green Book” won the same award, thus initiating its Oscar campaign).

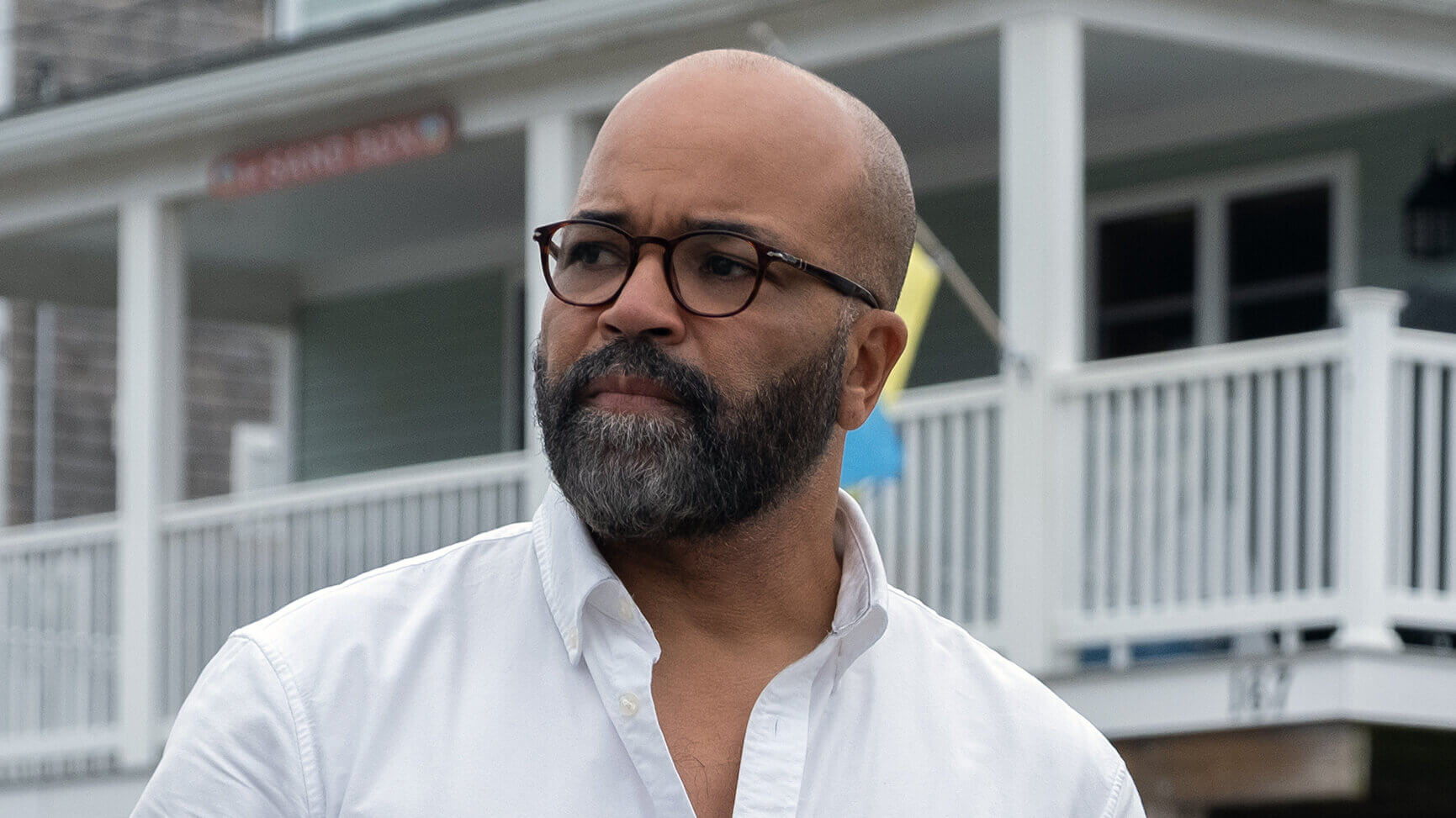

Despite being torn between two extremes, the screenplay still appears, alongside the outstanding performance of Jeffrey Wright, as one of the brightest points of “American Fiction.” Cord Jefferson came into the world of cinema from the world of television series. Before making his directorial debut, he was known as a prominent screenwriter, working on “The Good Place,” “Succession,” “Watchmen,” and “The Good Place.” His experience in television pays off: “American Fiction” sparkles with funny, incredibly intelligent dialogues that drive the action, leaving no room for a breather. However, the film fares worse in terms of direction: visually, there’s hardly anything interesting here. Each shot is flat and staged without much thought. As a result, Jefferson’s debut sometimes feels like… a full-length episode of a series, where the story is told dryly and without any further purpose.

However, in the final scenes, the debutant rises to the heights of directorial ingenuity, staging three different endings based on Monk’s own experiences. The white director chooses the one where the police kill the main character during a literary awards ceremony. Exiting the hangar on the film studio lot, Monk notices a black extra dressed as a slave. The men greet each other with a subtle nod of the head. This small gesture expresses a lot: I see it primarily as silent acceptance of the rules of the game. A game where satisfying others’ needs and expectations will always be valued more than authentic self-expression.