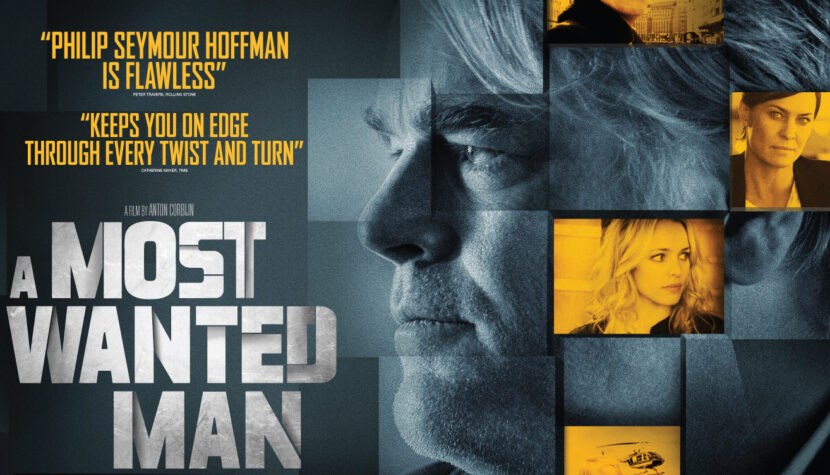

A MOST WANTED MAN. Blood-freezing thriller with excellent Hoffman

Issa Karpov (Grigori Dobrygin), a half-Chechen, half-Russian Muslim affiliated with various terrorist organizations, illegally makes his way to Hamburg. He arrives to claim the inheritance of his deceased father, which is stored in the bank of Thomas Brue (Willem Dafoe). The amount Issa can claim is significant, though not explicitly stated in the film, but known to be at least eight digits. Immediately, he attracts the attention of the anti-terrorism unit led by Gunther Bachmann (Philip Seymour Hoffman). They begin to monitor him, track his movements, investigate his connections to past attacks, and try to predict the purpose of his presence in Europe. When vast amounts of money are involved, powerful institutions must get involved. Issa’s appearance in the German city sets off a chain of events.

After some time, the Americans also take an interest in Karpov – as they are primarily the ones fighting terrorism. This time, the CIA is represented by Robin Wright, repeating her performance from House of Cards. In the role of Martha Sullivan, she is equally calculated, heartless, cool, dignified, and ruthless. It is an intriguing and well-written character, but even more outstanding is Philip Seymour Hoffman. A Most Wanted Man

Director Anton Corbijn and screenwriter Andrew Bovell unfold a complex network of dependencies, connections, and interests. There is a very clear hierarchy in this world, and the creators guide us through it: from anonymous small-time crooks, we ascend to the top. The director navigates this territory skillfully, indicating each character’s competencies, who is trying to surpass them, and who is balancing on their boundaries – as brilliantly played by Hoffman’s Gunther Bachmann. On one hand, he is a careerist, on the other, he has a bit of an idealist in him. It’s quite a paradoxical personality mix, but surprisingly, it works very well in this film. Gunther was sent to Hamburg because one of his investigations in Beirut ended in significant failure. In Germany, on much safer ground, he is supposed to take a break. Sit on the bench for a while because the game for the highest stakes is already overwhelming him.

Therefore, Karpov’s case becomes a lifeline for his career, a chance for rehabilitation. An opportunity to return in a grand style. However, he doesn’t forget to be humanitarian; he always remembers that it’s not just about professional success – hundreds of human lives are on the other side of the scale. Bachmann is a difficult-to-decipher character, intricately written. Corbijn and Bovell managed to create a fascinating character based on John le Carré’s book, of course. This is even more commendable as they never delve into his private or personal life; we always look at him from a certain distance – a man defined by the work he does, shaped by it. There is probably nothing else beyond it. Bachmann is practically never alone. He constantly holds a cigarette in his mouth and keeps a flask in one of his suit pockets. These are the only props for this character. We don’t peek into his past; we don’t see pictures of daughters in his wallet, we don’t know about an ex-wife. I speculate, but I think his life couldn’t have been any different. Superficially, he’s just another overweight alcoholic, another tired middle-aged man.

Yet, Gunther Bachmann has the face and silhouette of Philip Seymour Hoffman, who once again injects an unprecedented amount of charisma into the character he plays, giving it a tired yet intelligent look. His audible breath, so often distinct, makes us feel like we are truly witnessing a complete creation. The actor perfected his character down to the last detail. Hoffman is practically never off the screen; he completely dominates over all other characters. This allows him to nuance his character very well and play on many of our emotions. Bachmann is a multi-dimensional, unpredictable character. Hoffman perfectly expresses all its complexity – not only on the purely human – biological level (although that is a significant achievement as well). Because his Bachmann is primarily a “political animal.” Only through his work does he have a reason to live. It’s a character that one can explore for a long time, break down into its basic elements, and one that you want to return to – see again and get to know more closely.

Bachmann encapsulates all the doubts that may plague a person dealing with terrorism in the 21st century, trying to understand it. It’s not as if we, Europeans and Americans – people of the West, are helpless victims, and only we have the right to judge the attacking Others. In Seymour Hoffman’s interpretation, Bachmann changes his attitude several times, modifies his policy. He is an incredibly aware person of his role and the consequences of potential decisions. Therefore, the ending of A Most Wanted Man is so painful. It does not bring a satisfying resolution; despite numerous attempts, someone will always suffer. Corbijn invites the viewer to discuss, raises several questions. In the end, when the great actor steps off the screen, we are left with several unresolved issues and a lot of doubts. This is always a sign of good cinema.

Everything works very well in A Most Wanted Man. The plot unfolds slowly – it needs to be sipped calmly and slowly to be best enjoyed. Technically, the film is perfectly balanced and consistent. Corbijn doesn’t try to be as much of an aesthete as he did in Control or The American. This time, the script takes precedence. The cinematographer avoids creating metaphors and comparisons – the dialogue is the most important. The cold autumn color palette gives the film a suitable character, well corresponding to the calculated and heartless politics of the emerging organizations, and the cold corridors, interrogation rooms, and gray offices where crucial decisions are made.

We should detach A Most Wanted Man from the context of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s tragic death. Not because this character draws so much attention, not because the character he played attracts looks. It’s just another excellent creation in his legacy. Perhaps slightly inferior to Capote, maybe a bit better than Moneyball. It’s still an unreachable level for many. These adjectives don’t really matter because the art of acting significantly escapes a simple assessment – it affects the viewer on different registers.

A Most Wanted Man reminds me that cinema lost an actor who gave films an extraordinary depth – enriching them with a rarely encountered and incredibly precious aroma. I know that we will start missing him quickly. I think all cinema enthusiasts will add a completely different meaning to the title of this film than proposed by the film’s plot.