WHAT? The World in Chaos: Polanski’s Risqué Comedy Decrypted

The absurd is that which has no purpose… Cut off from its religious and metaphysical roots, humanity is lost; all human actions become irrational, futile, “suppressed”. Eugene Ionesco Notes et Contre-Notes

In an alienated world, we lose our bearings; everything becomes absurd. In this context, the grotesque is a game with the absurd (Ein Spiel mit dem Absurd) and at the same time an attempt to master and tame it. Polanski’s films often begin in an atmosphere of complete freedom, cheerful spontaneity. However, the viewer engaging in the game with the creator is drawn into the intrigue, deprived of independence, and the carelessly summoned phantoms fill them with horror. No one can break free. Horror combined with comedy is the essence of grotesqueness. What?

The screenplay of the little-known film What? from 1973, like most of his greatest works, was written by Roman Polanski together with Gerard Brach. A certain crafted common style is revealed here in a characteristic way. However, in no other work by Polanski does the absurd penetrate so deeply into the fabric of the piece. Loosely connected episodes, detachment from everyday logic, the lack of cause-and-effect relationships between events, playing with normal perception, absurd dialogues that do not lead to understanding between characters—all of this causes disorientation in the viewer. The effect of the uncanny and the strange arises from abstracting fragments of reality from their usual environment and context and juxtaposing them in a manner devoid of natural order and logic. From this arbitrary or accidental combination of incongruous realities emerges a new reality resembling a hallucinatory vision of the surrealists. A surrealist would call this reality la surréalité. It is a kind of absolute reality, called “superreality” by André Breton, which arises from the merging of two seemingly incompatible states, like a dream and wakefulness. It is not a reality with a purely psychic, mental existential status; it remains rather inseparably linked to external reality. It connects with a certain point in the mind where life and death, the real and the imagined, the past and the future, the communicable and the incommunicable, the above and the below, cease to be perceived as contradictory.

Surrealist works, if we consider them a projection of individual subconsciousness, do not yield to unambiguous interpretative efforts to determine their meaning. By their nature, they are ambiguous and evoke many different associations. They provoke rather a playful interaction with the audience, a game that aims to prompt the imagination and mind of the viewer to co-create the superreality.

In the case of a film work, the viewer then accepts without reservations the fluid transitions of one phenomenon into another, the questioning of logical motivations, and the weakening of temporal and spatial relationships. A viewer assessing the film What? according to the principles of traditional aesthetics finds themselves in a situation akin to the protagonist, Nancy. It is a situation of being lost and unable to find meaning in the observed reality, ultimately leading to a state of being besieged by a hostile world.

Nancy of What? navigates the increasingly branching meanders of reality but does not get closer to her journey’s goal. Similar to the protagonist of both of Lewis Carroll’s novels: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, Nancy gets caught up in a whirlwind of strange events and entangles herself in all the surrounding oddities. The curiosity and perspective of Alice looking down the rabbit hole lead to a transition to a world balancing on the edge of wakefulness and dreams, governed by the logic of dreams. Nancy, fleeing from persistent men, jumps into a mini cable car, which takes her to a picturesque villa overlooking the sea—and from that moment she enters a reality governed by its own laws, situated on the edge of reality.

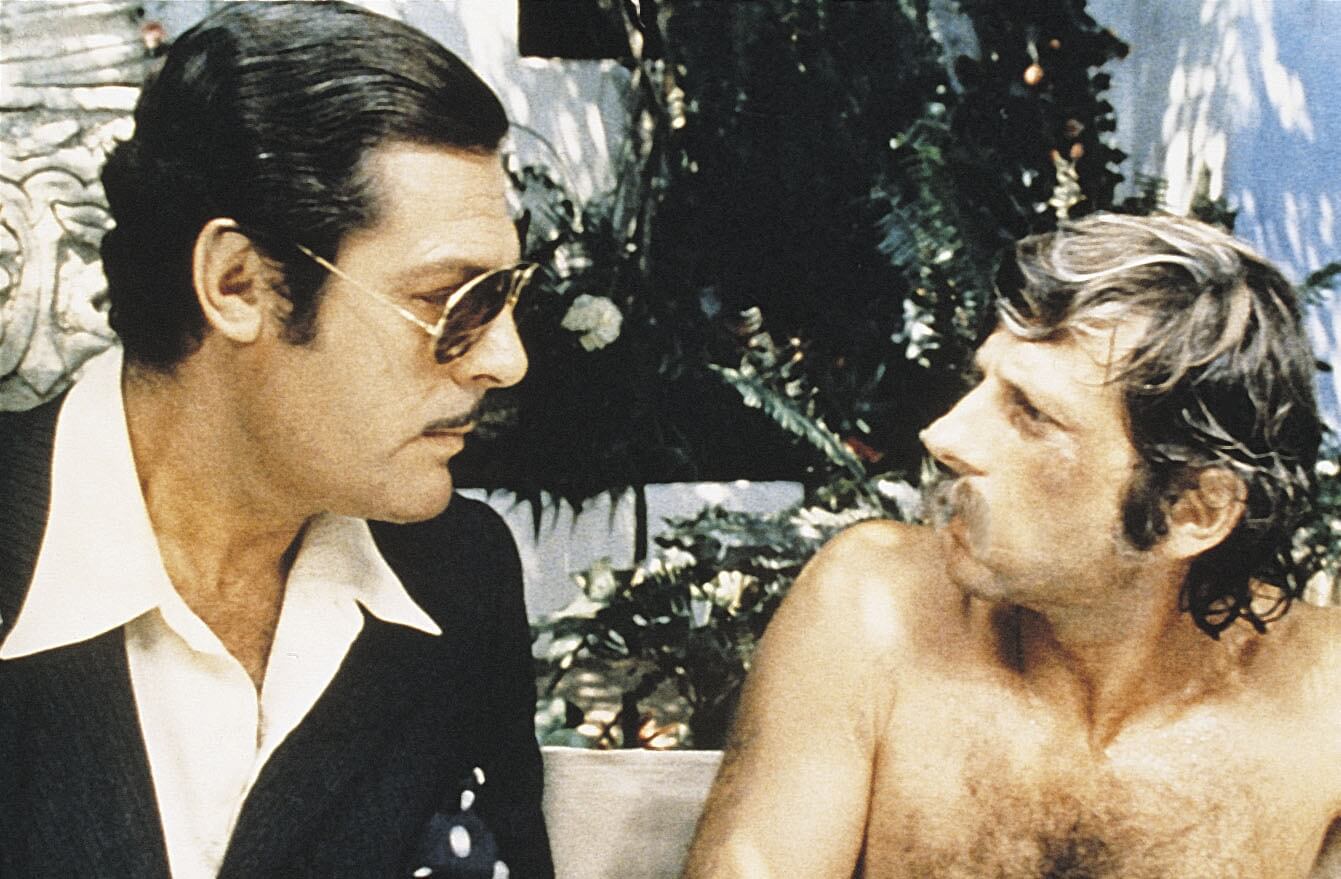

A servant takes her for a guest and, with the greatest obviousness, locates her in one of the rooms. Over the next two days, the girl will participate in unbelievable events in which the house’s residents will also take part. Nancy, constantly exposed to their traps, will become the object of erotic desires. The villa, full of bizarre characters, is guarded by a diabolic dog, which, like Cerberus, guards the entrance to this Edenic garden. Among the house’s peculiar inhabitants stands out Alex (Marcello Mastroianni), a life-weary playboy. Nancy also meets a former pimp with a humorous nickname, Coco Halfwit, a dreamer named Jimmy who compensates for his sexual frustrations with excellent cooking, the erotomaniac Tony and his nymphomaniac girlfriend Lollipop. The gallery of strange characters also includes a lesbian couple and the piano-playing house manager Giovanni. To this unusual company joins the aggressive and perverse Mosquito (Roman Polanski), who tries to shock everyone with continuous harpoon shooting. Later, an even more peculiar priest appears, along with a middle-aged American couple and the house owner, Noblart, an old and wealthy art collector. The panopticon of oddities is completed by his caretaker, the Nietzsche-reading German nurse Gertrude.

Nancy, with all her innocent naivety, gets entangled in many love adventures. The thematic plane is presented satirically, through comedy reminiscent of burlesque. The creation of the naive protagonist, who, along with the viewer (or reader), enters an unknown world, belongs to a proven narrative convention that Polanski used in his film. Nancy is a female counterpart to Voltaire’s Candide; like him, she is experienced by the world. She also resembles Justine from de Sade, an innocence constantly exposed to perversion.

In What? Polanski creates a comic version of a known and popular plot scheme. Contemporary sexual fashions are mocked; the director presents a wide range of erotic preferences in a distorted mirror. The most common relationship is the sadomasochistic one. Former playboy Alex invites Nancy to his room in the tower, where, wrapped in a tiger skin, he will demand to be subdued. The sadistic side of his nature is revealed during an excursion to a small island, where he digs up a chest, dons the stored 19th-century police uniform, and subjects Nancy to an increasingly threatening interrogation, which is a pretext to tie her to a branch and whip her. Also notable is the reduction of Nancy as a sexual object to the level of an animal. Fleeing from the final chase—the hunt by the villa’s residents—Nancy hides in a doghouse. An artist who unexpectedly and without purpose paints Nancy’s leg blue treats her entirely like an object.

What seems to be a trivial anecdote, variations on erotic themes hide more serious motifs of human objectification, the entrapment of an innocent being in a hostile world, and the impossibility of genuine contact between people. Each of these motifs, however, is marked by Polanski’s specific humor. Horror and comedy coexist here, as in the grotesque. The lack of communication between the film’s characters is expressed in dialogues conducted always in the convention of pure nonsense and employing absurd humor.

Already at the beginning of the film, there is a scene where Nancy, right after arriving at the villa, admires a painting by the Irish artist Francis Bacon (a depiction of Pope Innocent—a free reinterpretation of one of Velazquez’s paintings). The girl looks at the painting and, with expertise, declares: Bacon, which the housemaid understands as a desire to eat ham and replies that the kitchen is unfortunately closed. Sometimes the dialogue shifts into a collision of separate monologues, as in the scene where Nancy asks the men painting the wall in the tower about Alex’s whereabouts, and they respond: You could have just said you wanted a different color.

In What? Polanski primarily realizes the playful function of a game with the viewer. He uses a full range of techniques and styles. The viewer may be amused, for example, by the inappropriateness of situations and character behaviors, such as when Alex, dressed in a police uniform, demands Nancy’s passport and driver’s license while she is completely naked. The comic effect is created by ironically used alienation effects (Verfremdungseffekte), like in the scene where Nancy lies on a moonlit beach, and in the background, Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata plays. Polanski often uses film techniques borrowed from comedy of errors. He also employs slapstick, as when Nancy opens a door in the middle of the night from which an enormous amount of cleaning supplies fall out with a crash while searching for her bedroom. The protagonist is constantly looking for some missing piece of her clothing, with objects continually disappearing around her.

The absurd constituting the plot layer, in the sphere of dialogues and character actions, is accompanied by the absurdification of Polanski’s characteristic tropes from typical entertainment cinema, particularly the unusual use of the surprise effect. The presented reality is a multitude of unforeseen events, constant surprises, and logically unconnected incidents. The whole world is crazy, one might say along with one of the characters What?. Analyzed in terms of realism and probability, the world shown in the film would have pathological features. The dispersed narrative could correspond to disjointed thinking, and the absurd humor would signify a hebephrenic joy of life. Nancy’s behavior, full of naivety, would suggest a neurotic regression to a state of childhood.

The film can only be analyzed on the plane of absurd play with the viewer, as this is the only status—the cinematic playfulness—that the creator assigns to it. This precludes any psychological interpretations from the outset. The director even mocks all such interpretations a priori, playing with well-known and widely accepted Freudian symbols that function as stereotypes of collective imagination. The film’s iconography is largely created by these very stereotypes. In What?, there is no image devoid of symbols of feminine eroticism (wardrobe, chest, room, sea), masculine eroticism (tower, harpoon, knife), or symbols of sexual union (swinging on a swing, Nancy and Alex riding a water bike together).

Polanski deliberately directs the viewer’s attention to these symbols, choosing a phallic shape even for an insignificant scenic element like a lamp. Another effect used by the creator is the humorous animization of objects, such as a pen that ‘disappears’ on its own, being swallowed by a hole in the wall. The director’s ironic approach to potential psychoanalytic interpretations of his film also influences the shape of the dialogues. Mosquito—the man with the harpoon (played by Polanski himself, another example of detached humor)—introduces himself to Nancy as follows: They call me Mosquito because I have a mighty stinger. Want to see? You probably think it has something to do with sex? Information about Alex’s difficult childhood and incomprehensible complexes is conveyed in a similarly playful tone.

If we do not succumb to the director’s suggestions and accept the legitimacy of psychoanalytic interpretation, Nancy’s final departure would point to the theme of death (according to Freud, departure means death in a dream). It is significant that Nancy’s journey through the strange and alien world is accompanied by Schubert’s String Quartet in D Minor with variations on the theme Death and the Maiden. One of the last sequences of the film, depicting the death of the villa’s owner, Noblart, is also adorned with a musical punchline, a fragment of this very Schubert quartet. However, this death is presented in the film in a farcical convention (as grotesque also treats this theme) and must be taken within the context of an absurd joke.

The music used illustratively also contributes to disrupting the illusion of the plot, emphasizing the artificiality and conventionality of the film world by naming and ‘signing’ certain images. The director directly intervenes in the fabric of the work, juxtaposing shots of the moonlit beach with Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata and the mentioned Schubert piece with appropriate images. The Brechtian alienation effect is also achieved through the direct intervention of the demiurge director in both the sound and visual layers—the latter through the ironic treatment of Freudian symbols.

In this way, the creator emphasizes the autotelic function of the film text (the work refers to itself). An interesting phenomenon of mutual reflection between the film’s structure and dialogue indicates another way of realizing this function. For the first time in Polanski’s work, the effect of déjà vu is so directly defined in the conversation between Nancy and Giovanni at the piano. The information in the dialogue corresponds with the main principle of shaping the film’s structure—constant repetitions of individual elements. Noblart’s deathbed confession, expressing doubt about the unquestionability of the real existence of the only empirically accessible reality, and the final gesture indicating the conventionality of the film’s plot have a similar provenance. They stem from a specific relationship between the demiurge artist and the surrounding real world, a relationship based on ontological and epistemological doubt.

In the final shot, the main film characters define themselves: We’re just acting in a film, it’s just a film.

Alex – What? What film? What?

Nancy – What? That’s the title of this film.

In the final sequence, which forms a frame binding the film together, there is a return to the realistic convention similar to that of the first sequence. Consequently, at this very point in the film, the expression of the perverse play with the viewer, the autotelic destruction of the film illusion, gains deeper significance, suggesting the illusory nature of the only reality accessible to our senses.

The motif of the absurd game between reality and its reflection in art permeates all layers of the film, becoming a structural theme of What?. It finds expression even in the naive form of Nancy’s diary notes, which comment but do not explain the meaning of the events happening, just as the demiurge artist cannot explain anything to the viewer.

In the film’s dialogues, we find allusions to the works of Nietzsche, Heraclitus, and the Bible. The paintings of Géricault, Bacon, and van Gogh, the music of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, quotes from the works of Buñuel, Fellini, and Welles influence the shape of Polanski’s cinematic vision but do not constitute new meanings in the film.

The villa owner, Noblart, is an art collector. Even his name humorously refers to this theme (noble art). His entire life, as he says, he preferred reflection over reality; before his death, he concluded that he prefers reality over its reflection in paintings. Yet reality continuously eludes his reason, worse—even his senses. Noblart confides to Nancy before his death: Take that armchair, for instance. Believe me, there are moments when it seems to me that I’ve never seen it, and even worse—sometimes I doubt whether it even exists at all. (…) Day by day, I ask myself the same simple questions and find that I know the answer to them less and less often. In fact, I understand nothing anymore.

Let us juxtapose these words with Polanski’s oft-quoted confession: The older I get, the more I am certain that nothing is certain, and the less certain I am of certain things. Associating the film What? with the personal diary of its creator might go too far, but one thing is certain. For the first time in Polanski’s work, confessional and autotelic motifs have manifested themselves so directly.

Words: Malgorzata Kulisiewicz