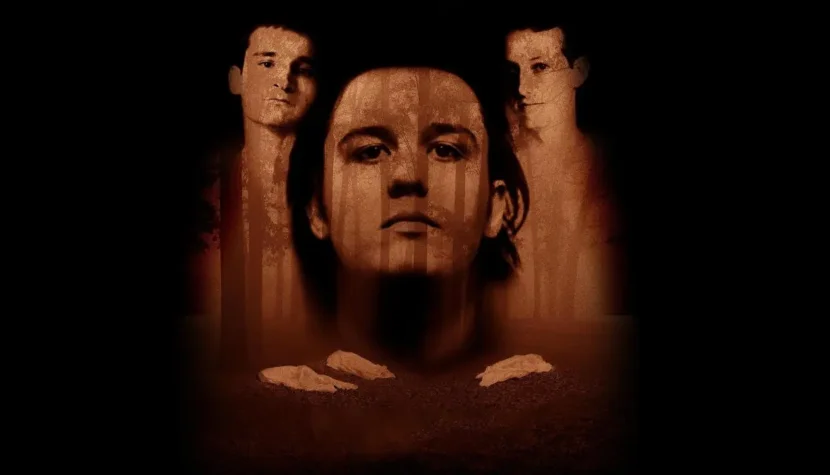

THE WEST MEMPHIS THREE and the Satanic Hysteria Explained

But let’s start at the beginning.

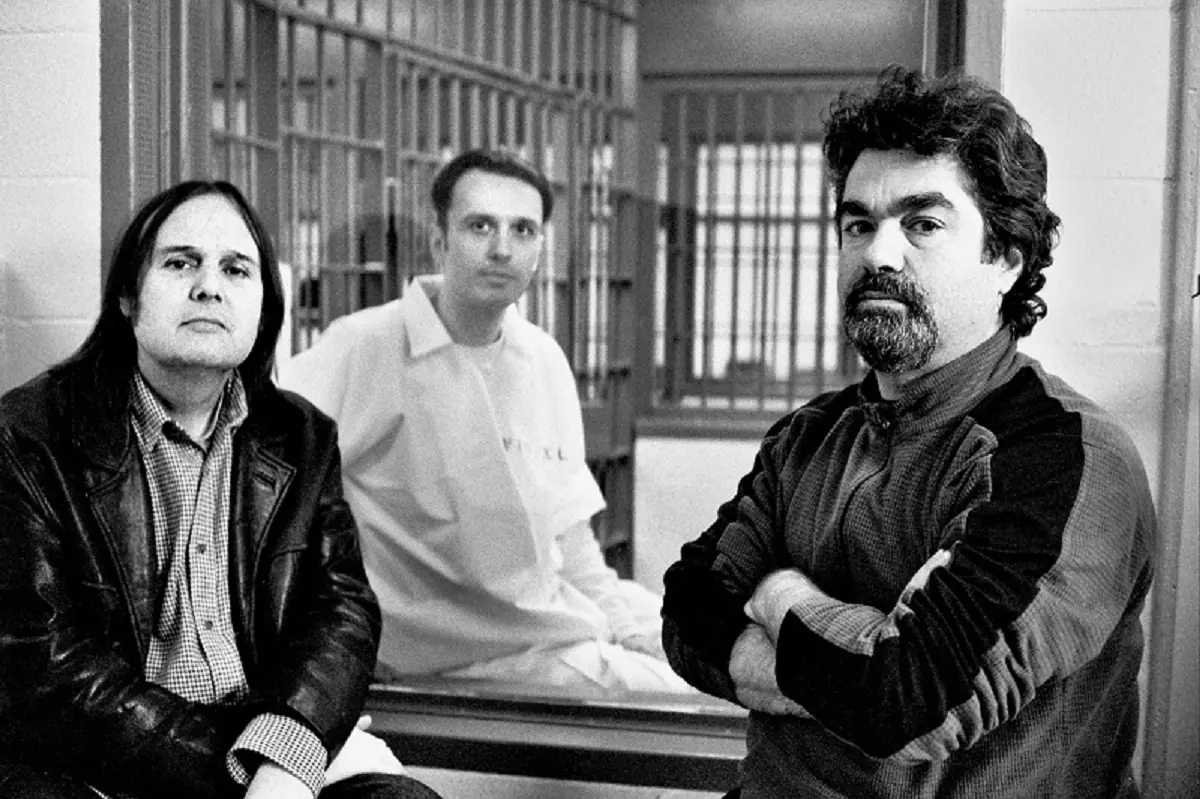

In the late 1990s, there was probably no one in the United States who hadn’t at least briefly encountered the case of the West Memphis Three. This was due to the incredible popularity of the documentary film produced by HBO, Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills, directed by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, who were involved in the case almost from the start, continuously gathering material. The following two parts, Paradise Lost: Revelations and Paradise Lost: Purgatory, continue the story, accompanying the WM3 over the years and thus becoming the only such historical record of a witch hunt and miscarriages of justice. The trilogy was summarized by the 2012 documentary West of Memphis, produced by Peter Jackson and directed by Amy J. Berg, as well as — in a way — the feature film The Devil’s Knot, based on the book by investigative journalist from Arkansas, Mary Leveritt, of the same title. Colin Firth and Reese Witherspoon starred in the lead roles.

But let’s start at the beginning

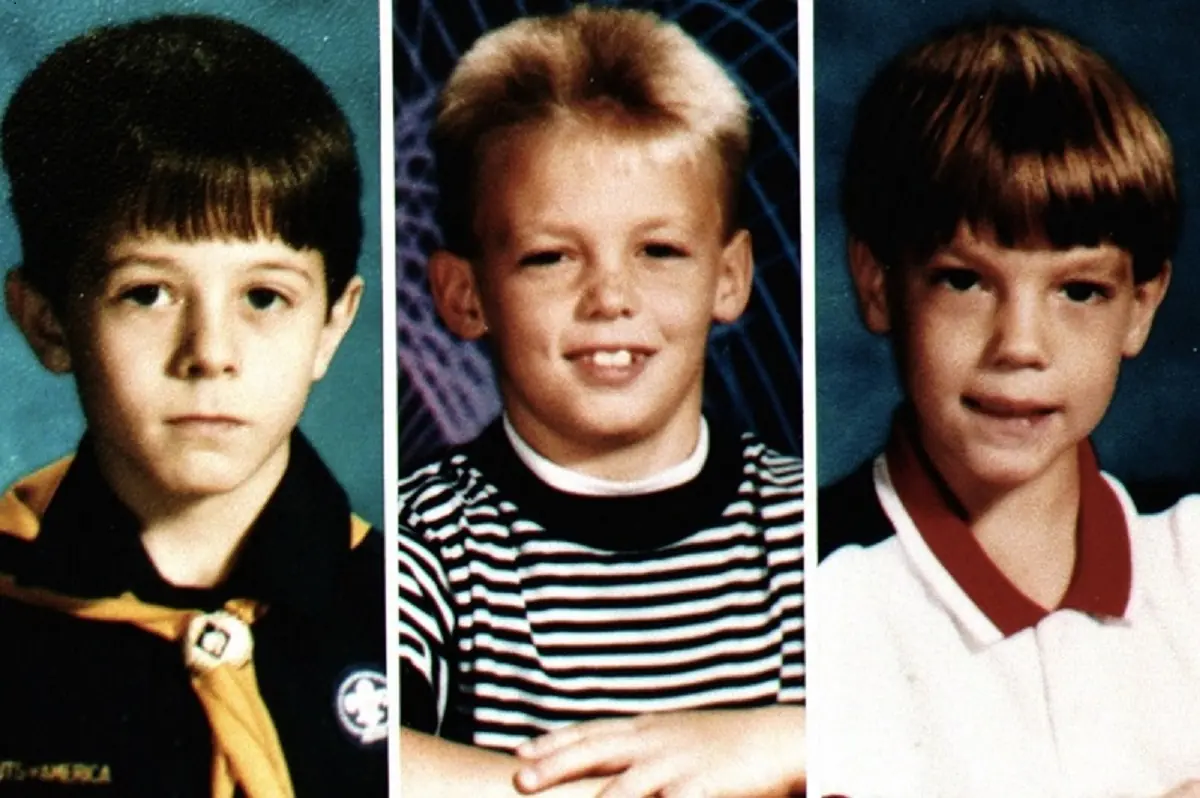

On May 5, 1993, in West Memphis, Arkansas, Pam Hobbs reluctantly allowed her eight-year-old son, Stevie Branch, to leave the house. The boy insisted, wanting to show off his new bicycle to his best friend, Michael Moore. Pam relented but instructed Stevie to return by 4:30 p.m. Shortly after the boys left, their peer, Christopher Byers, knocked on the door. Pam told him that they had already left, and excited, he turned around and ran to catch up with them.

Hours passed, and Pam had to go to work. She was angry that Stevie hadn’t kept his promise, but didn’t think too much about it. Her husband, Stevie’s stepfather and the father of her other child, daughter Amanda, drove Pam to work and picked her up after her shift. It was then that the terrified woman learned that her son had not returned, and no one knew what had happened to him and his friends.

Many years later, three neighbors independently testified that it was Terry Hobbs, Stevie’s stepfather, who was the last person seen with the boys. At 6:30 p.m., he was standing on the doorstep and shouting at the children playing nearby, telling them to come back immediately. Hobbs denied seeing Stevie, Michael, or Chris. Initial searches yielded no results. It wasn’t until the following day, during a new search, that officer Steve Jones noticed a child’s shoe on the surface of a muddy inlet leading to a drainage ditch. He alerted his colleagues and began searching more thoroughly. Soon after, three naked, mutilated bodies were recovered from the water. The boys had been tied up with their own shoelaces, covered in wounds, and one of them had been castrated. Preliminary examinations suggested that the boys had been sexually assaulted, beaten, and tortured. According to a later coroner’s report, Byers died from the injuries he sustained, while Branch and Moore drowned.

West Memphis was stunned and terrified. It was hard to imagine a more brutal and perverse crime. A perpetrator was needed, and needed quickly. Several suspects emerged: Chris Morgan and Brian Holland, a local ice cream vendor and a local drug addict; an unidentified Black man, whom the manager of a local restaurant had seen “confused and bleeding” in a women’s restroom on the evening after the boys’ disappearance. Perhaps everything would have unfolded differently if it hadn’t been 1993, when the nationwide hysteria surrounding the so-called Satanic Ritual Abuse (SRA) had not yet subsided, especially in smaller towns. Satanic cult signs were being seen everywhere, police officers were attending courses on occult murders and ritualistic victims, and anyone could become a suspect.

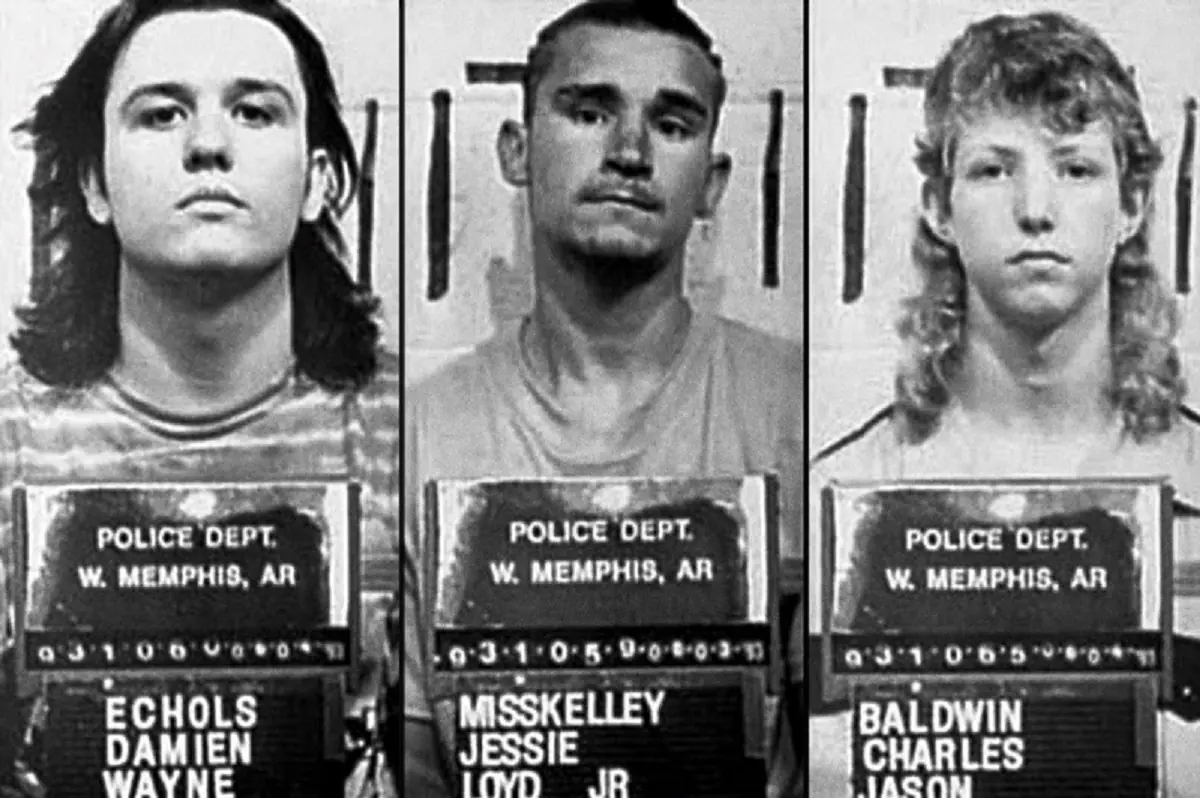

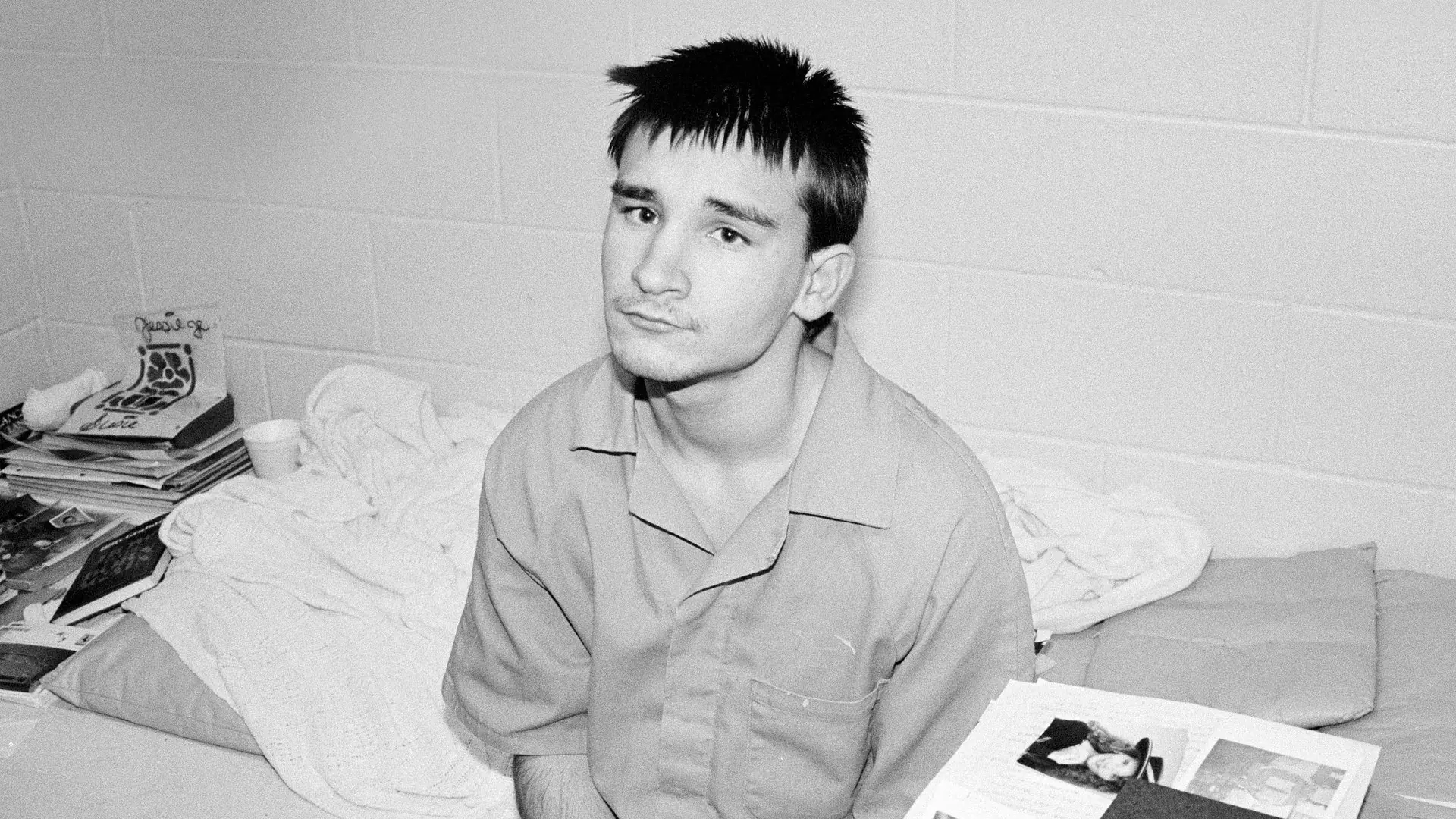

It was almost expected, as the residents of West Memphis thought. Wasn’t there talk of animal carcasses found in the woods the previous summer? Hadn’t someone spray-painted graffiti of a pentagram on a wall? The investigation turned its focus to Jessie Misskelley, Jason Baldwin, and most notably Damien Echols, the most suspicious of them all. Seventeen-year-old Jessie, with an IQ of 72, on the borderline of intellectual disability, was known in the area for his quick temper and tendency to get into fights. He knew Jason and Damien from school and the neighborhood, but they weren’t particularly close. However, it was from him that the police began their crusade, rightly predicting that he would be the easiest to break. After fourteen hours of continuous interrogation, Jessie was ready to say anything to make it stop. He confessed that he, along with Jason and Damien, had attacked the boys. He claimed to have seen Damien cut their bodies and drink their blood. He claimed to have seen them being raped, choked, and tortured. He said he stopped one of them who tried to escape. Sounds clear enough, right?

There was, however, a problem. Jessie could not provide any correct details. It was around noon. The boys had not gone to school. “Think,” the interrogator smoothly interjected, “was it already dark?” “Ah, so it was later.” “Five o’clock?” “No, too early.” “So maybe six? Or seven?” Jessie could not recognize the boys in photos until he was clearly told who was who. He confused facts and the sequence of events. He repeated like a parrot everything the police officers suggested. He recounted the entire story in the form that was circulating in rumors and newspapers at the time. Often sensational details, which later turned out to be unfounded in reality. But that was enough to arrest Jason and Damien. Jason was sixteen at the time, but he looked no older than fourteen. Small, quiet, and shy. It was quickly assumed that he certainly wasn’t the instigator, but rather would do whatever Damien asked him to.

Eighteen-year-old Damien Echols had a rather bad reputation in this conservative, religious neighborhood. It wasn’t so much due to petty offenses like vandalism or shoplifting, because that could happen to anyone. The issue lay elsewhere: one only had to look into his eyes to see that he was the embodiment of evil and had no soul. Damien dressed in black. He admitted to being a follower of Wicca. He had black hair, a pale face, and listened to heavy music. He cut his arms with a razor blade. He was simply odd, an outsider, a rebel, surrounded by “followers” (a pregnant girlfriend, his sister, Jason Baldwin), making him a perfect fit as a charismatic leader of a “cult.” Before Damien even testified, the entire neighborhood—starting from the parents of the victims to the judge—was convinced that he had surely sacrificed the boys to the devil, drinking their blood to gain strength and power. Or something along those lines. There were small obstacles, which, however, proved easy to overcome: Jessie retracting his statement, alibis provided by witnesses, the lack of physical evidence linking the accused to the crime scene, and the absence of any (other than occult) motive.

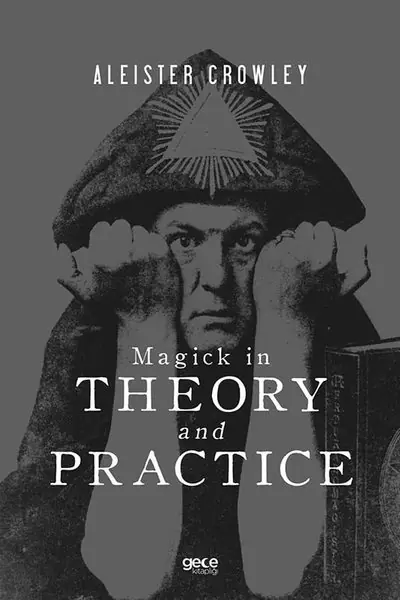

To testify for the prosecution, an expert was called, a man with a degree earned from correspondence courses, who took on the Herculean task of finding connections between the crime’s modus operandi and the occult. He informed the shocked jury that May 6 was the date of the full moon, during which Wiccans celebrate Esbats, and that on the night of April 30/May 1 was Beltane, a Wiccan festival. The expert did not mention that Wicca has absolutely nothing to do with the devil, as it does not acknowledge his existence. Instead, he focused on the symbolism of the number three and the three victims. As evidence in the case, he presented Echols’ Book of Shadows with a pentagram on the first page and books on magic, in which Echols allegedly highlighted passages related to human sacrifices and drinking blood. Damien didn’t help himself much, displaying an attitude that observers interpreted as dismissive. He claimed that he bought the books secondhand and that the markings had been there before. Most likely, someone had been preparing a paper, because there were also notes and dates in the margins. However, the prosecutor had one more arrow in his quiver. Did Damien know who Aleister Crowley was? Yes, he did. Didn’t Crowley claim in his writings that blood and human sacrifices were sources of the greatest power? Crowley also claimed he was a god, Echols retorted, adding that he was not a follower of Thelema. Then why, pressed the prosecutor, did he write this note, this particular evidence?

I was practicing writing names in different alphabets

And whose names were these?

Mine, Jason’s, my son’s… and Aleister Crowley’s.

A collective gasp swept through the courtroom.

I open Magick in Theory and Practice (yes, I own a copy), and it turns out that Crowley used his own name to present the key to his incredibly complex alphabet. If I were to attempt linguistic experiments, I’d probably start with his surname too. We won’t delve into this intricate issue, it’s just a side note. I’ll add that it is nearly impossible to engage with neopaganism in any form (which Echols openly acknowledged) and not encounter Crowley sooner or later. Wicca is a religion of self-improvement and the constant pursuit of knowledge, but an openness to knowledge is not evidence of a crime.

After the expert and Crowley, the final nail in the coffin came from the coroner’s testimony. He spared no graphic details as he described exactly how the boys were tortured and tormented, how Chris Byers was castrated, and how each wound and incision was made. And although the prosecution had a few more witnesses (most of whom had either retracted their statements over the years or openly admitted to lying), these three elements were likely sufficient.

|

Jessie Misskelley was sentenced to life imprisonment for first-degree murder and two consecutive 20-year terms for second-degree murder. Jason Baldwin was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Damien Echols was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Jessie Misskelley was sentenced to life imprisonment for first-degree murder and two consecutive 20-year terms for second-degree murder. Jason Baldwin was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Damien Echols was found guilty and sentenced to death.

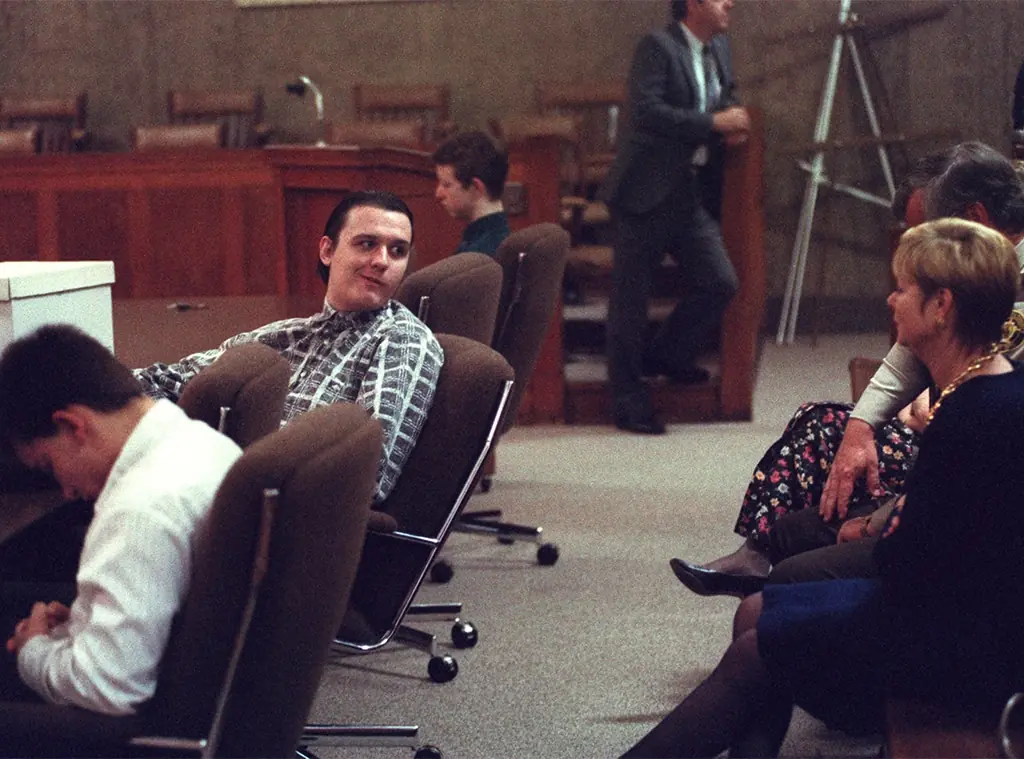

The camera closely follows the faces of the two boys as the verdict is announced. Jason is not surprised. While Damien is the philosophical type, his best friend, despite his young age, has the mind of an analyst. Even after Jessie’s verdict was announced a few weeks earlier, Jason had no illusions about his chances. The prosecution and his own defense attorney tried multiple times to convince him to testify against Damien in exchange for a chance at freedom. Each time, he firmly refused.

That would be a lie. And my mother raised me to despise lying.

Damien, on the other hand, looks like a person who has just received a strong blow to the head and hasn’t yet fully realized what has happened. He quickly blinks to regain his composure and maintains a stone-faced expression, his trademark throughout the trial. When asked if he wants to comment on the verdict, he shakes his head. Jason, however, firmly says, “I am innocent.”

The directors of Paradise Lost will say that his mind couldn’t grasp the translation of “I didn’t do it” into “I’ve been convicted.” He assumed that innocence guaranteed safety under the law. In his closing statement, the prosecutor described Echols as “a man without a soul.” This hurt him so deeply that, even twenty years later, he would still remember those words.

The prosecution and the media built an image of Damien Echols as the sociopathic leader of a cult, blindly followed by Jason. But the Damien we see in these early days — still a child, an awkward teenager with problems, playing tough for the cameras, yet clearly scared — is far from that image. He’s a person who worries about his friend, worries about the families of the murdered boys, fondly recalls the pets he cared for, does not flirt or manipulate. He’s a man who would later speak in incredibly moving and sincere words about his love for his wife, Lori, whom he met while in prison. A man who exchanged hundreds of warm, affectionate, open letters with her. Above all, he is a man who had no motive, if we dismiss the satanic nonsense without basis in reality. Either Damien Echols was born the best actor to ever walk this earth, or the justice system failed completely and sentenced him to death for a crime he didn’t commit, based on an occult expert’s sworn testimony that Satanists paint their nails black and wear dark clothes.

What would he say if you showed him a picture of, say, the band Slipknot…?

The same applies to Jason, who was judged exactly like Damien – based on appearances. Since he was quiet and less outwardly expressive than a friend, he was presumably susceptible to manipulation and weak, blindly following like a sheep. But again, that is not the Jason we see. We see a man who always firmly holds to his beliefs. Who does not yield even under immense pressure when his entire future is at stake. Tough and decisive in his views at just sixteen, equally unyielding ten, fifteen, and twenty years later. Disciplined, gathering knowledge, working on himself. This is not the type who would mindlessly follow a cult leader and easily have his brain washed. This is the type who would slam his fist on the table and say, “This is wrong,” when you least expect a reaction. Nonetheless, the fact remains: all three of them are behind bars, society is convinced that justice has been served, and a pair of filmmakers are putting together a documentary to present to the general public.

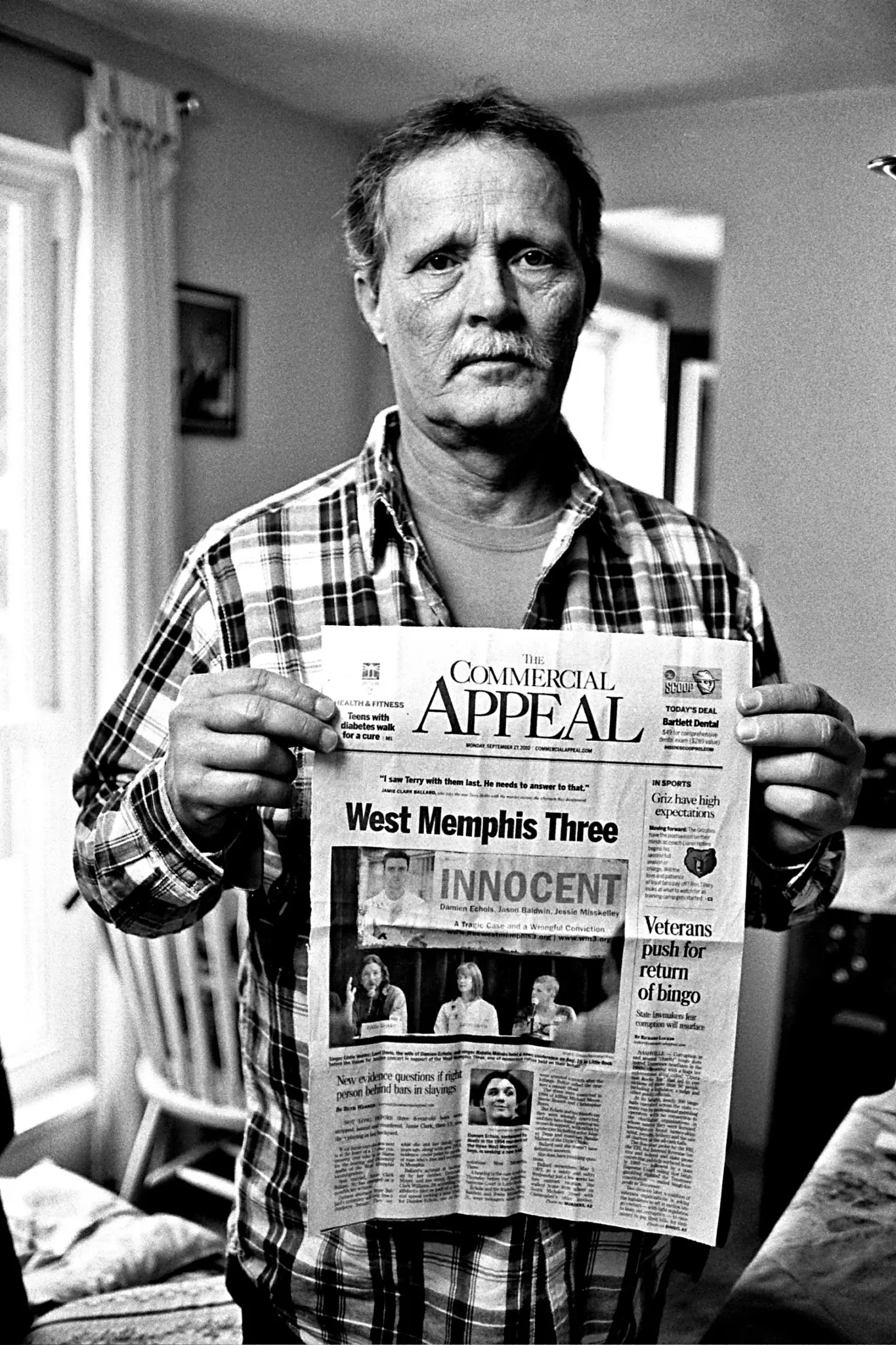

The effects of this presentation are seen in the second part, where the main character is John Mark Byers, the stepfather of one of the murdered boys and the first serious suspect to emerge against the convicted trio. As the years pass and Damien’s appeals, still heard by the same judge, bear no fruit, a grassroots movement called Free West Memphis Three begins to form on the internet. People from all over the United States, even the world, come together to picket outside the courthouse. Byers is present at every one of these pickets and, still fully convinced that the right people are in prison, gets into verbal arguments whenever he can. Imposing in height, towering over everyone else, with a deep and penetrating voice, he is a uniquely distinctive personality. During the filming of part two, Byers suffers from a brain tumor and is constantly on strong painkillers and antidepressants. He often fabricates stories, for example, giving at least four versions of how he lost his teeth and got dentures. This was particularly important at the time because new analysis of the evidence suggested that bite marks were found on one of the boys and they didn’t match any of the three convicted. Meanwhile, Byers’ wife, and Chris’ mother, Melissa, dies under suspicious circumstances. According to John Mark, it was due to “a broken heart.”

Byers’ problem likely lay in the same thing as Damien’s and Jason’s original issue. He was judged by appearances and quickly became a suspect due to his unusual personality. Byers loves cameras, loves the audience, and enjoys playing different roles. When he speaks, it’s too loud; when he gestures, it’s exaggerated; when he does something – he dramatizes his actions to the absurd. His theatrical flair goes hand in hand with a tendency to fabricate. He plays the role of a grieving husband the way he imagines it, but paradoxically, in his particular case, this does not mean that he isn’t truly a grieving husband. Shakespearean kneeling and clutching his head are his duties in front of the cameras. In fact, being at the center of attention and events makes him feel like a fish in water, living the adventure of his life – without diminishing the true tragedy he faced with the grief of losing his stepson. The grotesque image of Byers setting fire to symbolic “graves” of Misskelley, Echols, and Baldwin and stomping on them while howling will remain with me forever.

In part two, we also get to know Damien better through his chats with his supporters. He himself has doubts about Byers. He will officially apologize for this later. He talks a lot about his new spiritual journey, reflections on God, religion, and spiritual balance. While in prison, Echols meditates under the guidance of a Japanese Zen Buddhism master. His marriage to Lorri Davis in 1999 also took place in a Buddhist ceremony, three years after she wrote him her first letter, moved by the screening of Paradise Lost. Over the course of their relationship, they exchanged over five thousand letters.

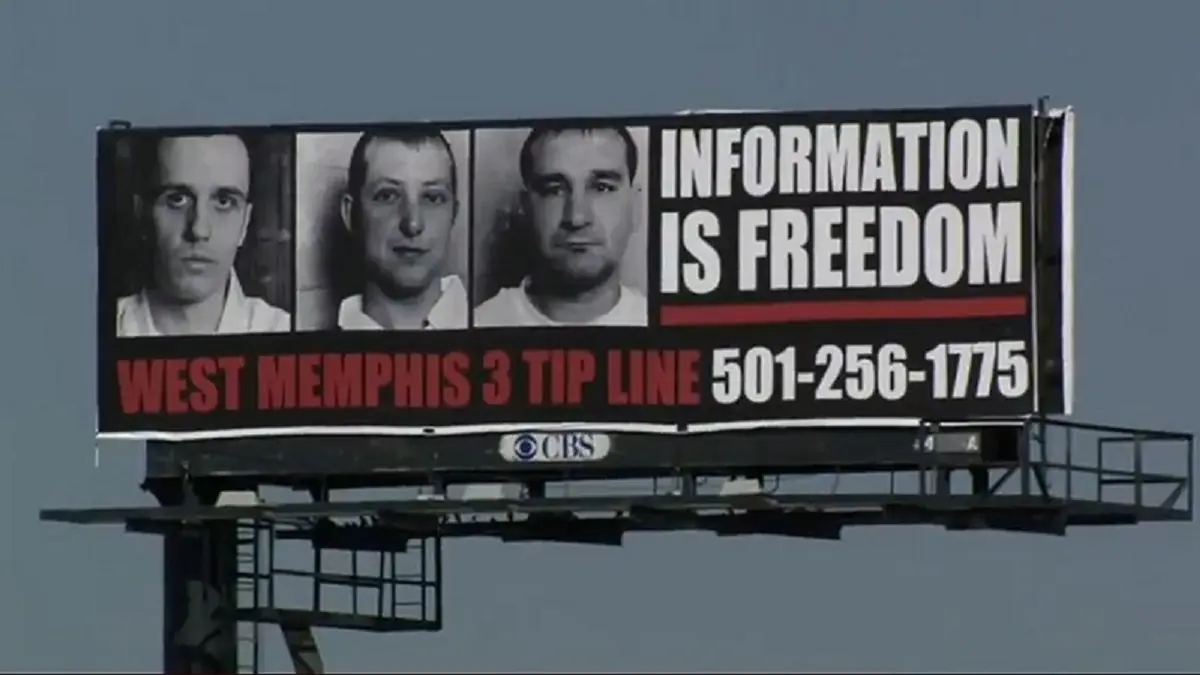

Lorri became the most dedicated and zealous activist for the Free West Memphis Three movement, tirelessly working to spread awareness of the case wherever she could. The most zealous, but certainly not the only one. Eddie Vedder and Johnny Depp, both still close friends of Damien Echols, Patti Smith, Nick Cave, Bob Dylan, Peter Jackson, members of the Wicca community, and many others got involved. For proponents of conspiracy theories, this was another proof of the existence of a satanic cult within Hollywood circles, supporting “their own” under the guise of deceptive liberalism. However, the movement mainly resulted in raising funds that allowed for new tests on the evidence. And then came the bombshell. First of all, none of the evidence collected at the crime scene matched the DNA of Jessie, Damien, or Jason.

Secondly, several independent pathologists – including the mentor and expert pathologist who originally appeared in the case – stated that the wounds on the boys’ bodies (including the alleged castration of Chris Byers), previously considered a key piece of evidence for the ritualistic nature of the crime, were actually the result of animal scavenging, particularly by turtles, and were post-mortem. Thirdly, inside one of the knots used to bind the boys, a hair matching that of Terry Hobbs, the stepfather of Steve, was found, and another hair matched the DNA profile of a neighbor who had provided Hobbs with an alibi. Fourthly, several key witnesses for the prosecution – notably Vicki Hutcheson, who allegedly accompanied Damien during the orgiastic and brutal event, and a fellow inmate of Jason Baldwin – retracted their testimonies and apologized.

In light of the discrediting of the “ritualistic” elements and sexual violence, for which there is also no definitive evidence, the crime now presents itself entirely differently. Most importantly, it becomes personal. The motivation shifts from “lust” to “anger.” The person who killed these boys knew them, and probably quite well. That’s what the great John Douglas says, and I believe him. It wasn’t a weak teenager, but an adult man, strong enough to maintain control over three victims, likely with a history of violence, aggressive in relationships with close people, especially women, and posing as a macho.

When Judge Barnett resigned from his position and plunged into a political career, the convicted men were given a chance for an appeal in light of new evidence (or rather, a re-examination of the existing evidence). The hearings kept getting postponed – first to the fall, then to the winter… Echols’ and the others’ allies began to realize that while undermining the conviction was possible, actual release could still be a long way off. Meanwhile, the opposition began to realize that they were likely to lose the case in court. This is not a presumption but a direct quote. Echols’ health began to deteriorate, and he quickly started losing his vision. After eighteen years on death row and a decade in solitary confinement, this was to be expected. A loss would mean a lawsuit for damages running into millions for the state of Arkansas. In this situation, the prosecution offered the West Memphis Three a compromise in the form of the so-called Alford plea (the case of North Carolina v. Henry Alford from 1963). The precedent could just as well be called a paradox, because in short, it involves the defendant pleading guilty, while still maintaining that they are innocent of the charges against them.

I am innocent, but the state sent me to prison for it. When I plead guilty, they release me. This is not justice. This is a parody of justice,” said Jason Baldwin.

Jason Baldwin initially firmly refused to sign the agreement. He was ready to fight to the end to prove his innocence 100%. But he also understood that the stakes were not only about him, but in fact, Damien Echols’ life. Ultimately, he too gave in.

The DNA analysis turned out to be sufficiently convincing both for John Mark Byers and for Pam Hobbs. Byers officially appeared wearing a Free West Memphis Three t-shirt and became as passionate an advocate for the innocence of the three men as he had previously been a proponent of their guilt. He too was outraged by the application of the Alford plea. “The state is covering its own backside. This should not have happened. They are innocent,” he rumbled, as usual surrounded by a group of listeners and a few cameras. Pam, meanwhile, long divorced from Terry, wonders if she had unknowingly shared a bed with the man who killed her son.

The figure of Hobbs indeed raises doubts. Byers even prepared a pro and con list. In the “pro” column, one can find a criminal past, violent behavior, work in a slaughterhouse, a hair found at the crime scene, no confirmed alibi, and family connections to one of the victims. “Why was I scrutinized so closely, but not him?” asks Byers. However, the attempt to build a case against Hobbs is the weakest moment in the entire Paradise Lost series, as well as in the concluding West of Memphis. The genesis of this is easy to understand – if we support the innocence of one side, we want to further reinforce the message by presenting a real suspect. To highlight the flaw in the legal system by presenting a possible perpetrator who, for almost twenty years, walked free in plain sight and no one cared. Thus, it’s understandable – but completely unnecessary, because, except for Hobbs’ questioning during a defamation suit he filed against Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks, we mostly have speculation and rumors.

Out of nowhere, witnesses appear, claiming that Hobbs’ nephew had been entrusted with a “great family secret.” In a break between shooting hoops and hitting the basket, he allegedly said: “You won’t believe what my father told me, my uncle killed those boys from West Memphis.” A relative of Pam Hobbs, who had kept quiet for eighteen years, suddenly remembers that Stevie was not only regularly beaten by his stepfather but also sexually abused by him. An old neighbor recalls an assault in the shower, when Hobbs unexpectedly broke into her house and attacked her in the bathroom. All of this sounds highly unconvincing, unnecessarily clouds the picture, and fits into the atmosphere of a witch hunt, which we were supposed to be distancing ourselves from in the first place. If you don’t want to be judged hastily, don’t do to others what was done to you. Nonetheless, the figure of Amanda, Hobbs’ daughter, appears tragically. She remembers nothing from her early childhood and always adored her parents (she even has their names tattooed on her wrists). At the time West of Memphis was filmed, Amanda looked terrifyingly thin, wasted, and trembling, after several rehab stints and constant relapses. One inevitably starts to wonder whether her lack of memories and addiction were a consequence of some repressed childhood trauma? Another victim of the West Memphis Three drama.

In 2011, Jessie Misskelley, Jason Baldwin, and Damien Echols were released from prison after serving over 18 years – guilty and innocent at the same time. In the early period after their release, they became something of celebrities, primarily due to the many people who believed in their innocence and fought for it. Their case served as an example that justice could prevail, that it mattered. Jessie, the only one who remained in Arkansas, kept away from the media spotlight. His father said he married his high school sweetheart and works in construction. Jason also married and, around 2014, expressed interest in studying law and dedicating himself to defending the wrongly convicted. He was also a co-producer of The Devil’s Knot. Damien was not happy with this. He thought the script was misleading and distorted many details, which led to a significant cooling of relations between the friends (if they even still existed, rather than being a public declaration for the sake of the crowd). Echols dedicated himself to art and writing, traveling for lectures, and, along with his wife Lorri, campaigning for the abolition of the death penalty. He remains interested in the occult and magic. Like many of us.

The immense popularity of the Paradise Lost series also sparked many critical voices. There are still many people who believe in the guilt of the West Memphis Three. However, even those more reasonable (i.e., those who do not begin their argument with “the satanic conspiracy lurking to harm American children”) often base their opinions on circumstantial evidence, frequently repeating things that have already been proven false (such as the knife found behind Baldwin’s house or fibers from Echols’ shirt). The main argument revolves around Damien Echols’ long history of psychiatric treatment, tied to his fascination with the occult, as well as the fact that Jessie “repeatedly” upheld his incriminating testimony. Yet, even these two strong points have their flaws. Starting with the latter and completely disregarding the question of why a cult leader would choose a stranger and someone barely known to him as a ritual sacrifice, rather than someone from his close circle of “followers” – none of Jessie’s statements are factually consistent or fully aligned with the evidence.

As for Damien’s mental health, he received exactly the kind of care that any troubled teenager from a disadvantaged background living on welfare could expect – none. Damien, in turn, acted exactly as one might expect from a troubled teenager from a disadvantaged background when thrust into the clutches of an institution where he didn’t belong. As he often did during stressful situations at the time of the trial, and much later – he adopted a defiant attitude and showed off. It’s easier to survive when people fear you, and if you don’t have the physical tools, you cope in other ways. Damien was never diagnosed as a sociopath. He was never diagnosed with schizophrenia. He simply claimed that he was a sociopath, a schizophrenic, and a maniac. He said many things that were remembered, held against him, and used as evidence in the case – a case in which the alleged occult nature was now being questioned. I have seen many teenagers like Damien, and in part, I was one of them. That is why his medical history doesn’t particularly shock me. Supporters of the West Memphis Three’s guilt often fall into the trap of the complete lack of evidence against Jason Baldwin, apart from purely circumstantial ones (like the three types of knots – three perpetrators). For safety’s sake, they then say they doubt Jason’s guilt, but as for Damien… so how does one reconcile this supposed key piece of evidence – Misskelley’s testimony? It’s either this or that.

As for Devil’s Knot, it does not compare in any way to the book on which it was based – a 500-page piece of solid investigative journalism. The presence of Colin Firth or Reese Witherspoon (as Pam Hobbs, which greatly pleased Terry Hobbs) doesn’t help. It doesn’t measure up to the weight of the events it portrays, unnecessarily drifting into Hollywood sentimentality. It adds nothing to the case and, instead, irritates. However, the acting is decent – Kevin Durand as John Mark Byers is particularly interesting – and the courtroom reenactments are well-done.

As for the Paradise Lost series, like all documentaries of this type, it will face accusations of bias and taking sides in the conflict. In my opinion, however, it is an unprecedented account of a witch-hunt and a story of a parody of justice, of people chewed up and spit out by a broken system. And this holds true regardless of which side you look at: because if we believe that the state and prosecution decided to release three people, who they still believed to be guilty, in order to avoid trials, compensation, and stains on political careers, that too would be proof that something is very wrong with the way justice, order, law, and public service are carried out. While the wrongly convicted – and I firmly believe they were truly innocent – Jessie Misskelley, Damien Echols, and Jason Baldwin finally had a chance to rebuild their lives, the three 8-year-olds from West Memphis never saw justice served, and perhaps, like many others, they never will. There are many human dramas in this case, but none compare to the tragedy of those three victims. We can only remember their names and hold onto the hope that the one who did this will one day face the deserved punishment. And that the evil they caused will come back to them threefold.