Blood rituals, sects and evil forces, or PAGAN HORROR

When I write about the pagan horror trend in horror movies, I mean the kind of films in which the central motif is not so much the presence of supernatural / impure forces (which is basically an inseparable element of almost every story of this genre), but the ritual, cult organization that has grown around them.

Pagan horror

The basic core of the pagan variant of horror is therefore the confrontation of ordinary, unconscious protagonists (often lonely) with a traditional micro-community associated with primal, demonic forces. The themes of malevolent collectiveness, defilement of innocence and dark mediation with demonic deities through blood magic, sex and blood sacrifices recur. Within such a dramaturgical framework, a relatively large variety of variants is possible, but it is easy to extract common features of many films dealing with the subject of secret brotherhoods and occult sects. Due to the strong presence in the pagan variant of the horror of the village and folk themes, it can be considered a specific form of the so-called folk horror, focusing on folkloric scenery. The difference is that the horror in the pagan version would be targeted specifically at the pagan beliefs, cults and rituals present in this space, which orientation may sometimes exceed the folk envelope.

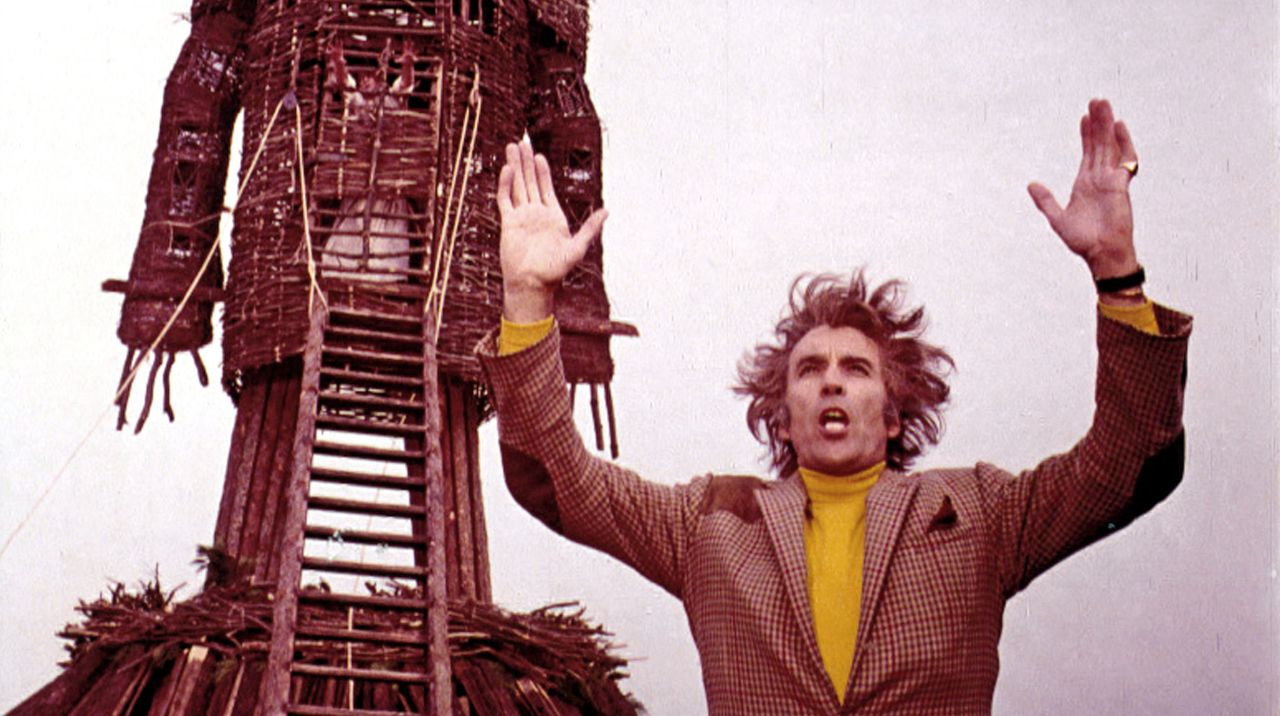

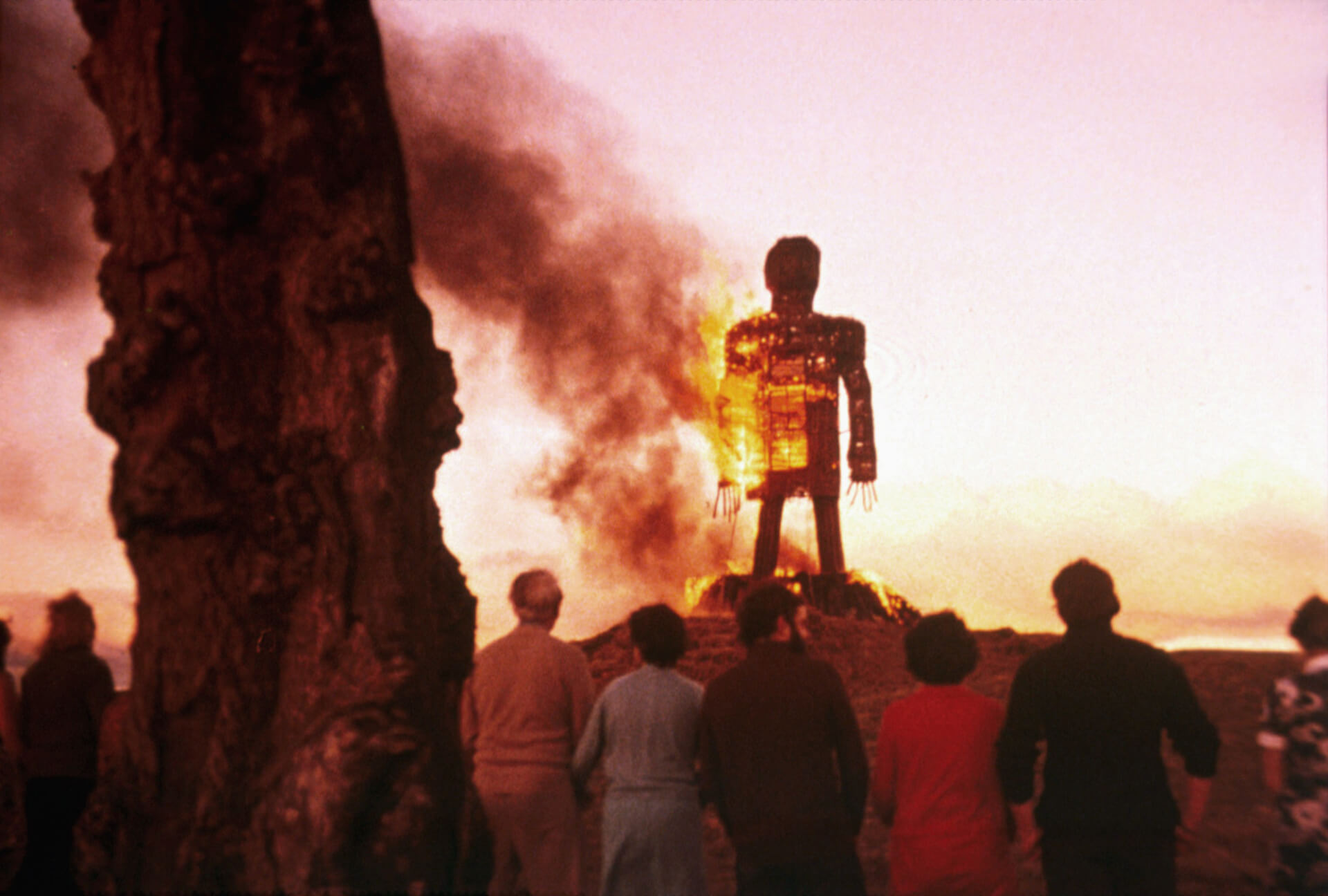

A classic implementation of this formula is, of course, the infamous The Wicker Man by Robin Hardy, in which a policeman investigating the disappearance of a teenage girl is drawn into the intrigue of the inhabitants of an island who want to perform a pagan ritual that restores the fertility of the land. We are dealing here not only with an exemplary plot scheme (the stranger is lured towards an archaic cult of the community), but also with an ideal exposition of the key tropes of the convention – the juxtaposition of a contemporary individual associated with state institutions with sinister, primal beliefs, the exposition of sexuality associated with the fertility of the earth and the anti-humanistic, bloody face of pagan religion. In a model form, the theme of a sect hidden under the guise of rurality and normality, centered around a charismatic spiritual leader who watches over dark rituals, also appears in The Wicker Man – the figure of the memorable Lord Summerisle can be considered an archetype of a demonic (literally and figuratively) servant of ancient deities.

Pagan themes, by definition, are part of the cultural tradition that fuels horror as a genre. The genesis of the aesthetics of horror in art is largely related to the world of folk tales and legends preserved in the structure of fantastic fairy tales, which, through, among others, the works of the Brothers Grimm and the incorporation of folk tales by pioneering authors of horror literature provided the emerging genre with a demonic imaginary. As a result, horror was intuitively rooted in folklore, with its magical thinking and primal fears caused by the untamed space of nature. There is also a pagan potential associated with the folkloric background of horror – folk religiosity is traditionally characterized by a certain syncretism, combining Christianity with more archaic forms of ritual, and the agricultural nature of rural communities suggests their connection with agrarian fertility cults. Thus, if we assume that horror is connected in its genealogy with folklore understood as a specific socio-cultural system, one of the elements of this heritage that permeates the identity of this genre is openness to the pagan element. This legacy is extracted and used as a core by horror movies like The Wicker Man and Midsommar.

Related:

Pagan element

In order to understand the essence of pagan horror, one must turn to the folk connotations of this trend. The motifs, characters and archetypes inspired by horror cinema taken from European (related Asian variant is a separate topic) folklore are largely of pagan origin, i.e. non-Christian (or pre-Christian) in the sense of the official interpretation of faith. Folk religiosity, identified today with religious orthodoxy, due to the specificity of rural life based on everyday experiences of coexistence with the natural world and the unevenness of the process of Christianization, in its former form was heavily saturated with elements that did not quite match the teaching of the Church. The world of folk beliefs and legends, which provided horror with inspiration, contained clear pagan accents, which had another effect in relation to horror cinema – such inclinations were noticeable in folklore from the perspective of the enlightened upper classes, which affected the way in which, from the perspective of bourgeois culture (of which, after all, cinema is a part) the country is perceived. Pagan horror explores this ambiguity – it follows a folk-inspired combination of fascination and fear of primal, inhuman forces (mainly nature) and at the same time responds to stereotypical ideas about uncivilized rural folk. The basic format of pagan horror, to which all its creators refer to some extent, is based on fundamental cultural oppositions derived from the opposition of culture to nature – urban contrasts with the country, education with superstition, humanism with cruelty, upbringing with eroticism, and morality with carnality.

In this perspective, paganism merges into one with Satanism and occultism – all three domains are located outside the borders of the Christian vision of the world, posing a threat to it. Therefore, the religious attitude to the vital forces of nature, which is the essence of fertility cults, is treated as tantamount to devilish action (it is worth recalling the laveyan maxim used by Lars von Trier as the foundation of the Antichrist – “Nature is the Church of Satan”), and pagan inclinations are often mixed with Satanism . This very important disambiguation for pagan horror is related to the tradition of Manichaean sects active primarily in France and Italy in the Middle Ages. According to heretics, the earthly world was created by the Evil God – i.e. Satan, equal to God – who was attributed supremacy over the earthly creation. Although the decline of the Manichaean sect of the Cathars dates to around the thirteenth century, the influence of their teaching may have lasted much longer, especially in smaller parishes. The Manichaeans provide a historical pattern for a sect identified with Satanism promoting a heretical attitude towards the world and the devil – an organization commonly appearing in horror.

Therefore, all stories in which occult rituals are directly addressed to Satan or another being of this type should be included in the category of pagan films. In this approach, pagan horror can be seen broadly as exploring the subject of sects and cults contrary to the Christian order. Thus, the antagonists in the pagan horror will be both real pagans who worship archaic deities and declared Satanists or occultists who refer to the devil’s power. Both Satan and those bearing pre-Christian names or nameless chthonic deities are in the eyes of the European cultural base of horror an incarnation of the same – unbridled pagan element that threatens the civilizational norm. More important than the evil demon itself in pagan horrors are sects, its followers and messengers, who pose a real threat to the world of the protagonists – regardless of whether any divine or devilish forces actually exist.

Classic matrix

The fertility of pagan themes in horror cinema can be proved by the sheer number of films using this theme – they can be counted in dozens (if not hundreds). It resonated most strongly in Britain in the 1960s and early 1970s, when there was a real flood of horror films focused on the subject of sects and the secret practice of witchcraft. Presented in 1973, the aforementioned The Wicker Man of Hardy can be considered a kind of crowning achievement, a magnum opus of a trend that has been strongly present in the genre for over a decade. Previously, this topic was John Llewellyn Moxey’s The City of the Dead (1960), J. Lee Thompson’s Eye of the Devil (1967), Terence Fisher’s The Devil Rides Out (1968) and Piers Haggard’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971). The more interesting films of the genre include Peter Sykes’ To the Devil a Daughter (1976) – one of the last films of the Hammer studio. Due to its abundance, this period can be considered the classic era of pagan horror, in which its grammar and characterization were established.

In the British school of the classic period of pagan horror (generally also counting as a variant of folk), the raw, classically Hammer staging directly showed the tension between rationalism and bodily vitality and mysticism, which is fundamental to this trend. The heroine of The City of the Dead is a history student studying witchcraft, unexpectedly discovered in a real form practiced by a mysterious brotherhood. On the other hand, in The Blood on Satan’s Claw, in a dialogue devoid of irony, the judge states that “there is no witchcraft”. However, the pragmatic realism of the protagonists is undermined in the films by the real presence of occultism and magic, most often practiced by the socially inferior, less “enlightened” – provincials, peasants, women and youth. Thus, there is a clear division into elite norms and plebeian paganism, which threatens the proper order. Bloody rituals designed to sway the deities into favor are here the negative of a properly functioning society, just as sensual energy is the structural opposite of controlled reasoning.

Importantly, although rationality and spirituality are confronted, the Christian faith is placed on the side of the undermined or distorted “normality”, which negates and fights the manifestations of pagan-satanic mysticism. However, this is an apparent contradiction – the real tension here is not the result of the opposition between reason and faith, but between culture and nature, in which the socially sanctioned, institutional faith in Christ is inscribed in the pragmatic structures of the official order, while its opposite are primitive, elemental rituals that escape the law. This is clearly seen in the role of sexuality in British classics such as The Blood on Satan’s Clawor or The Wicker Man – eliminated from the Christian vision of ethics, it is the core of pagan practices, connecting with natural fertility and the cycle of life. Pagan horror thus expresses the fear of the male, cause-and-effect world of what goes beyond the norm and moves the senses that escape rational control. In Eye of the Devil, Sharon Tate plays the young, attractive witch is the disturbing alter ego of Deborah Kerr’s maternal heroine, embodying the ambivalent potential of femininity beyond the rational organization of the world. Due to this specific location in the oppositional juxtaposition of mind and senses, eroticized women often play the role of a medium connecting a sect with a demonic deity associated with the elements of nature, while sensual femininity imbues secret rituals with sexual debauchery.

A significant motif is also the repeated localization of occult practices in the space of a peripheral province (usually British, but not necessarily – e.g. in Eye of the Devil the action takes place in France), where occult phenomena had a clear outline of the cultural heritage in which the local community was formed. On the one hand, this trope complements the dynamics of confronting the civilizational order with the primal pagan element, and on the other hand, it profanes the common (strong especially in the British tradition) image of an idyllic, idyllic countryside and province. The occult contamination of familiarity emphasizes the dangerous proximity of the folk sphere and the dangerous backwoods of nature. One of the most important treatments in the pagan horror trend is visible here – as a consequence of organizing the drama around the cult of evil (instead of evil as such), the basic optics is shifted from the domain of folk beliefs to folk itself understood as the antithesis of the modern, common-sense world.

Original (re)visions

More or less since the release of The Wicker Man, there has been a slight decrease in interest in the topic of secret assemblies practicing occult rituals. Horror movies with a pagan theme have not stopped being created, but since the advent of the era of slashers and gore themes of sects and secret rites have ceased to resonate so clearly in the genre. Posthumous cultists of the satanic-sectarian matrix rarely gain wider recognition, although there are works that stand out above B-class mediocrity, such as Ben Wheatley’s Kill List (2011) or Gareth Evans’ Apostle (2018), which try to breathe some freshness into well-established patterns. However, sects in cinema are doing well mainly thanks to visionary filmmakers reaching for the occult imaginary. If, after sketching the classical period, we were tempted to make a historical classification, the last four decades would be a stage of fragmentation for pagan horror, in which individual, original shots come to the fore, using, in addition to semantic tropes, also the aesthetic potential of paganism as a starting point for spectacular visions.

The avant-garde for this “late” approach to pagan-satanic themes can probably be considered Rosemary’s Baby – a film that is aesthetically and thematically close to the British classics filmed in parallel, but much more marked by the director’s original sensitivity (importantly, he also definitely abandons the provincial scenery). Polański’s film, using the motif of a sect and occult practices, goes in a more sophisticated direction – it engages psychological and social interpretations and strengthens the creative role of the film language. The Polish director bases the subjective narrative on a woman exposed to occult tensions, thus introducing a significant feminist perspective shift. Such mediation of the film vision through the experience of the female character (also performed earlier, for example in the folk horror film Demon by Brunello Rondi from 1963) along with the development of the trend became another important clue of pagan horror, signaling the problematization of the genre convention in which women’s agency is situated “externally” in the fundamental confrontation between rational culture and pagan nature.

Dario Argento achieved the mastery of rewriting the pagan motif into his own visions, drawing heavily on the pagan imaginary in his horror films. The famous Trilogy of Three Mothers (Suspiria, Inferno and Mother of Tears) is inspired by pre-Christian beliefs violently colliding with a twisted contemporary setting. Argento’s films can serve as a perfect example of the impact of pagan motifs on the overall impression of the film – although, for example, in Suspiria, the motif of witches hiding in a ballet school is seemingly just another of the tricks from the horror cinema arsenal – it triggers disturbing subtexts, casting doubt on the foundations on which modern society with its refined culture (symbolized by sterile perfectionist ballet) has been built. The Italian, rooted in the native tradition of the giallo, therefore proposes to infect the developed world with primal, terrible demonicity, analogous to the “pollution of rurality” by Gothic sects, which is key in the British lineage. Argento’s films weave pagan motifs into creative visions, transferring demonic inclinations to the level of film experience, the perception of which becomes intertwined with semantic tropes at the level of form.

In many respects, the tradition of pagan horror also includes the Antichrist, which is basically embedded in the non-horror tradition and evokes the current e.g. in The City of the Dead, the theme of researching the history of witches and explicitly exposing the demonic connection between women, sex and cruelty with the anti-rational world of nature. Von Trier’s film brutally exploits the primal drives antagonistic to rational, masculine culture, accumulating fear of the sexual element liberated from social control. In a somewhat similar tone, referring to the heroine’s single experience, an interesting, revisionist approach to the pagan theme was proposed in 2015 by Robert Eggers in The Witch. A folktale from New England. The American reversed the basic pattern by initially banishing the characters from the religious assembly, which catalyzes their encounter with the pure (exclusively available to them, without the mediation of the sect) pagan mysticism of nature. While in the classic model of pagan horror the satanic element is internalized in human nature at the level of a cult manifestation, in The Witch this is done through the individual heroine who submits (unlike in the model) to the pagan magnetism of the natural environment and independently creates the space of demonism, which is a form of mystical taming of man’s intuitive fear of unbridled nature.

Ari Aster enters the tradition outlined in this way, stretching between a conventional scheme and original reinterpretations. In his spectacular debut, Hereditary (2018), he reached for the classic formulas of pagan horror – the flywheel of the film was the activity of a mysterious cult that poisons the functioning of the protagonists’ family and in its bosom is confronted with rationalist skepticism and fear that gradually turns into paranoia of the main character. In addition, Aster used a directly treated imaginary of monstrosity, degeneration and evil associated with “ugly” Satanism. However, within such a classical framework, threads linking Hereditary with a psychological and dramatic approach to convention, derived more from Rosemary’s Baby than The Wicker Man, have been crammed into such a classic framework. Thus, in his debut, Aster combined two threads of the pagan trend, rewriting its classic matrix in a modern fashion. Midsommar continued in this path, with an increase in the significance of the ritual, folkloric setting. In Aster’s new film, hypnotic impressionism is supposed to correspond with a formally sophisticated approach to pagan themes, seen as an element with visual potential, while the plot itself connotes open drawing from the very heart of the folk-pagan horror trend. At the same time, this connection in the case of Midsommar seems more exciting than in Hereditary due to the anticipation of an even deeper exploration of genre matrices, opening the way to a revision of the foundations of horror, similar to what Eggers did in The Witch.

A revelation of horror

The power of pagan horror lies in its ability to evoke universal fear of a demonic threat, antithetical to the everyday order, which at the same time arouses fascination with its ritual and occult atmosphere. There is something intriguingly perverse about the degeneration of religious symbolism and the desecration of the sacred sphere committed by film sects, something that disturbingly moves intuitively and undermines the common perception of the world. The best works of the genre question the religious and social order, reducing evil to the actions of weak, cruel and corrupt people who, in the final analysis, are the horizon of the divine-devil struggle. The Wicker Man is not about whether the people of the island are right in their worship, whether their deity exists and will grant their requests, any more than it is about whether God will save Howie – the point of Hardy’s film is that every cult is carried out by man. It is the dark potential of supernatural human actions that is ultimately the source of the fear of breaking the order – and that is why there is so much potential in it.

Pagan horror is therefore a form of considering the relationship between the world-man-evil triad, which emerges from the violent juxtaposition of opposing orders. The genre recognizes a certain paradox inherent in the scenery and symbolism used, using it as its creative fuel. Looking at a conventionalized religious ritual inscribed in the social norm, we will feel that it is empty, but at the same time we will read from it the possibility of a certain vital spiritual energy. In pagan horror, this gap is bridged by filling the ritual void with a real mystical element, the cult antithesis of Christianity. It is a kind of radical, perverse fantasy about an encounter with the magical power of faith, in which it is discovered that at the center of it all is man, who gives meaning and shape to things and is the ultimate source of both good and evil. At the same time, he is no longer the same man as at the beginning – the one revealed by the pagan horror is a bizarre creature, as if degenerated, beautiful and vile at the same time. On this paradox rests the whole essence and ultimate achievement of the pagan thread in horror cinema.

This kind of discovery of the ambiguity of the central role of man in the face of pagan rituals, demonic evil and secret sects is something worth looking for in subsequent films dealing with these themes. The revelation of this horror is all the stronger, the more effective and spectacular the symbolism and scenery in which it is placed. A film based on expressive folk motifs can become a ritual in itself, evoking such a special experience of intuitive fear of confrontation with the nature of evil. In this context, Midsommar, built on pagan motifs, may become the crowning achievement of the subgenre’s aspirations to evoke the experience of primal mysticism and through it suggestively show the ambiguous relationship between man, the construction of the world and evil. To achieve such an ecstatic effect, a large dose of director’s bravado is necessary, taking the risk of entering the folk atmosphere, the eerieness of the ritual and reflecting the human perception of this world. Aster’s film should be a cinematic experience in the literal sense – a cinematic ritual dialogue with tradition.