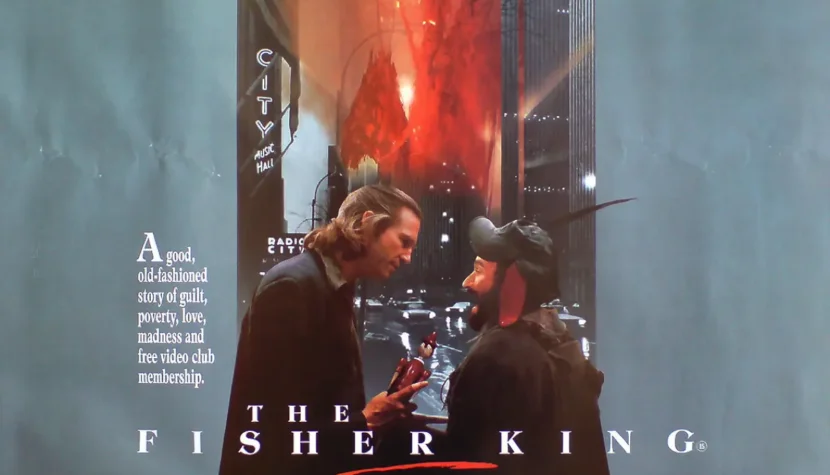

THE FISHER KING Explained: The Legend Behind Gilliam’s Movie

The director had had enough of dealing with the obstacles that accompany high-budget projects and was looking to take a break. Around this time, a script written by Richard LaGravenese landed on his desk. The story of a madman searching for the Holy Grail on the streets of New York was in need of a director.

Apparently, James Cameron was also considered for the job, but he had to decline due to the advanced production stage of Terminator 2. Gilliam—despite having worked on the scripts for all his previous films—agreed to take on the offer and immerse himself in the eccentric world of Parry, which fit perfectly with his imagination. It was an excellent decision. Thanks to this choice, we have one of the best films in Gilliam’s career, and it also features outstanding performances from Robin Williams and Jeff Bridges. The Fisher King, despite the passage of time, remains incredibly relevant and, simply put, deeply moving.

Within the Circle of Legends

When writing the script for The Fisher King, Richard LaGravenese did not hide the inspirations behind his text, which was brought to the screen by Terry Gilliam. The Fisher King, mentioned in the film’s title, is a rather mysterious figure who appears in various stories related to the legend of the Holy Grail. Similar figures can also be found in tales beyond those related to the mythical chalice or the knights of the Round Table.

For LaGravenese, the most important source of inspiration comes from legends involving characters associated with King Arthur. In these traditions, the Fisher King, also called the Wounded King, was the last guardian of the Grail, which didn’t always take the form of a precious chalice. Depending on the version of the legend, the artifact had both material and spiritual qualities, becoming a metaphor for values higher than wealth, glory, and the privileges they bring. All versions of the story agree that the last keeper of the Grail was seriously wounded or ill. He was kept alive by the magical power of the object—or perhaps by the idea behind it.

The king’s poor health significantly affected the condition of his lands. This is why, in stories about the Fisher King, barren lands are often mentioned as his kingdom. In every version of the Arthurian legend, the king awaits a brave soul who can understand the mystery of the Grail, find it, and thus cure the king’s illness. In earlier texts, this chosen one is Parsifal; later, companions like Galahad and Bors join him. Often, the act that had the power to heal the king and lift the curse from his lands was simply asking a question. Its content varies depending on the legend and interpretation, but the most fitting version for The Fisher King is from Wolfram von Eschenbach’s epic Parzival. According to the medieval text, the magical healing power came from Parsifal asking the Fisher King a question: My Lord, why do you suffer so?

When Parry, looking at the moon illuminating Central Park in New York, tells Jack the legend of the Wounded King, it turns out that the savior of the king and the kingdom was a fool who, with genuine concern, asked the suffering man what ailed him. When the king answered that he was thirsty, the fool gave him a cup of water. After the first sip, the festering wound disappeared, and the vessel turned out to be the Grail. In many versions of the Arthurian myth, Parsifal is afraid to ask any question, unknowingly condemning the king and his lands to suffer. During his first visit to the castle, the knight remains silent, as the rules taught to him discourage asking unnecessary questions. Only during his second visit, years later, does he decide to break the rules, lifting the curse from the Fisher King.

In this interpretation, Parsifal behaves like a fool, acting according to rules that don’t fit reality. In The Fisher King, Parry obviously plays the role of the Wounded King, while Jack is his Parsifal—who, for a long time, has much more in common with a fool than with the legendary knight of the Round Table.

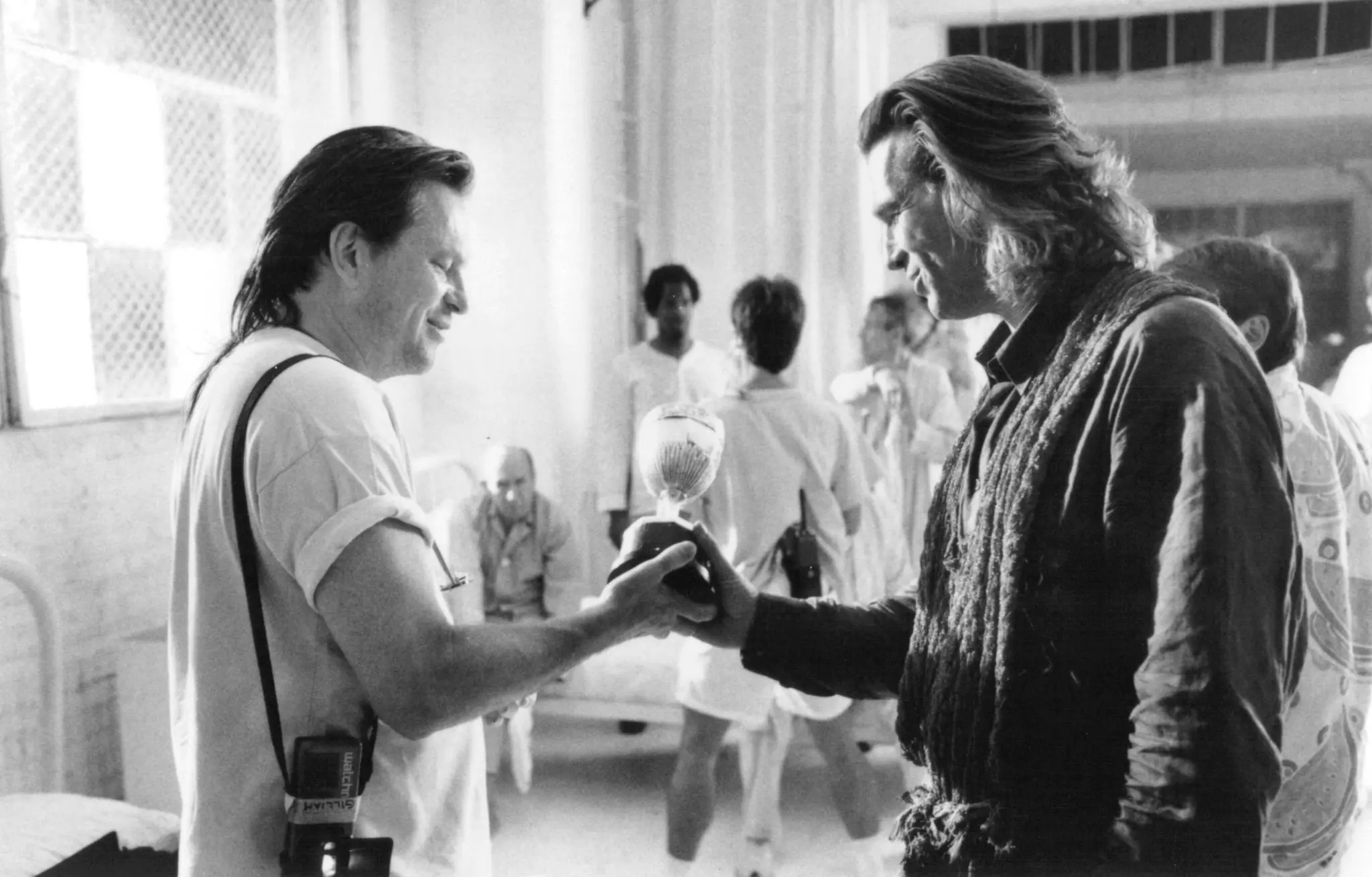

In LaGravenese and Gilliam’s variation of the medieval legend, the Grail, as a physical object, is just a meaningless trinket sitting on a millionaire’s shelf. It is, of course, located in a castle surrounded by a land far from perfect. When Jack steals the cup, its owner, like the Fisher King, is saved from death. But the most important element, both in the Arthurian tale and in The Fisher King, is not the object itself but the journey the characters must undergo to acquire it. What healed the king in Eschenbach’s myth was the simple question: “What ails you?” There was no need for battles with dragons, black knights, or dozens of typical trials from that era’s texts—just paying attention to the man and trying to understand him. The Grail gained its magical power only when ordinary people, not rulers or knights, were present. Parsifal’s gesture stripped the king of his royalty and the warrior of his knighthood. Stepping outside the code, taking off the mask, and simply caring about another person was the key to understanding the mystery behind the artifact.

This same dynamic is present in The Fisher King. When Jack brings the cup to the center where the comatose Parry lies, he too has shed his cynical mask, which had been cracking since that memorable night spent in a certain boiler room. Like Parsifal, Jack initially can’t step outside the established mental frameworks. Only through the journey to understand what the Grail truly represents does he open his eyes and, against all rules and common sense, allow himself to be drawn into Parry’s game. While the cup in the millionaire’s home remains just an object for Jack, its symbolism undergoes a complete transformation. Something that once seemed to him tangible proof of Parry’s mental illness becomes, by the film’s end, a symbol of longing for a friend. This shift echoes Parsifal’s question to the Wounded King: Why do you suffer? What ails you? Behind all of this is a simple sentiment: I want you to come back, to be happy again.

Within the Circle of Imagination

As Jack climbs the tower of Langdon Carmichael’s New York fortress, he casually throws out a line that vividly paints the city as seen through Terry Gilliam’s lens: Good thing people in this town don’t look up. It’s odd that such a statement is made in a place filled with towering skyscrapers, bright neon lights, and the ever-present glow hinting that while some people are laying their heads on pillows or sipping drinks at a bar, others are still working to increase the gross domestic product.

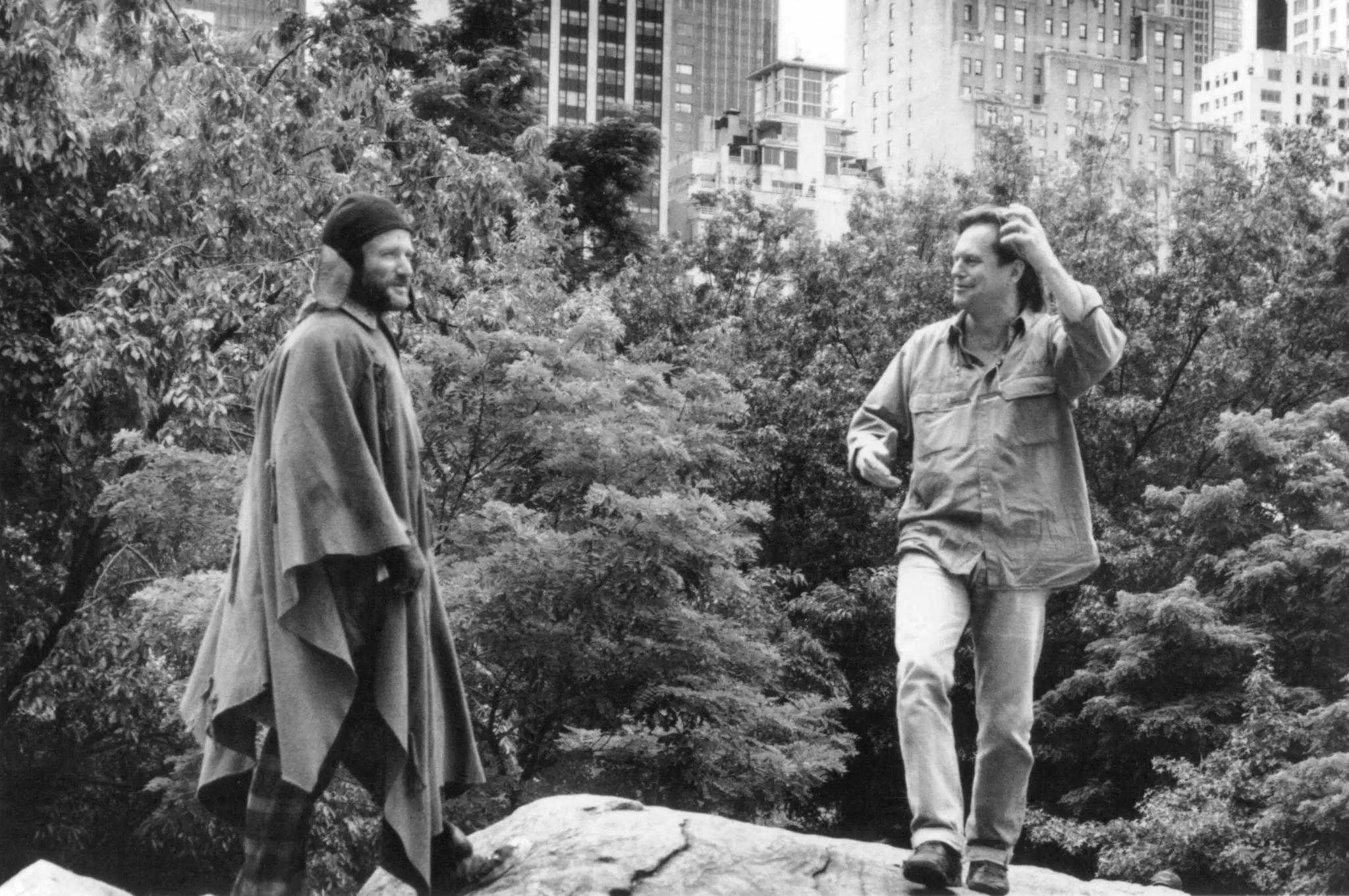

Gilliam’s New York is a city of gray sidewalks and glass office buildings that swallow people like the elaborate machines he designed for Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Almost every resident of the Big Apple has something weighing on them, preventing them from looking up at the clouds lazily floating over the green lawns of Central Park. Almost everyone is rushing, staying sane through small rituals that grow into sacred traditions—buying another trashy novel about true love, Wednesday dinners at a Chinese restaurant, or a drink at a trendy bar occasionally visited by life-weary desperados with firearms. The big city overwhelms, strips people of their identity, and throws them into patterns, forcing them to follow the crowd that forms the same lines and sits in the same traffic jams every day.

This is why everything valuable and interesting in Gilliam’s vision happens on the periphery, both literally—away from the center—and metaphorically, in the world of people who don’t fit the lifestyle promoted by the giant corporations dominating New York’s core.

Even when Gilliam’s camera explores places seemingly inhabited by outcasts and misfits, it turns out that among broken furniture, heaps of trash, and food scraps, there is more joy and hope than in the brightly lit streets of the better districts. A makeshift bonfire, lit with anything at hand by a gloved hand missing fingers, proves to be a better spot than the cozy fireplace in the mansion of a man who has theoretically reached the top of life’s hierarchy. Among the burning debris, people give thanks for another day and sing of love for New York and Gershwin. In the fortress on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, they pop pills to end a never-ending streak of success. In this world, the truly strange and ambiguous characters are the young men who visit the homeless to humiliate, beat, or even kill them. At first glance, they seem like nothing more than a gang of degenerates targeting people no one will look for. But when viewed from a broader perspective, it’s worth wondering if their motivation is really just a primal urge to display their strength. Maybe their violent attack is a defensive reaction, a sign of fear that someone lives outside the rat race and, despite having nothing, can still happily sing around a fire?

The fairy-tale world of Parry is not a simple ode to living outside the realities of adult life. Gilliam values imagination immensely, but its complete detachment from reality leads to the same tragedies as succumbing to the dictates of money. The waltz at Grand Central is indeed beautiful, but it cannot last forever. For the director, imagination is useful only if it leads to self-discovery and a connection with another person, who, by stepping outside mental frameworks and stereotypes, can reveal themselves to be more than a man in a dress, a jaded radio host drowning his sorrows in Jack Daniel’s, or a madman searching for the Holy Grail near Central Park.

Imagination is necessary to lift our gaze from the grime of the sidewalk and look upward, to realize that life doesn’t end between the revolving doors of an office building and the Chinese restaurant just a few eerily similar blocks away. In The Fisher King, we encounter the dynamic characteristic of Gilliam’s entire filmography, where worlds created within the human mind can either serve as a way to cope with life’s adversities or become a slippery slope leading straight into madness. When imagination becomes merely a form of escape, all that’s left is to glance over our shoulder and pray that we aren’t struck by the blade at the side of the Red Knight.

In the Circle of Companionship

Both in the layer that corresponds to the Arthurian legend and the one shaped by Parry’s imagination, The Fisher King essentially boils down to the same conclusion: the most important thing is human connection, the presence of someone close, and understanding from a friend. Without Jack’s help, Parry would never have been able to acquire the coveted Grail or win Lydia’s heart. Without Parry’s influence, Jack would most likely have ended his life in an emotional pit, caused by the tragedy that, paradoxically, brought the two men together.

In LaGravenese’s and Gilliam’s interpretation, the tale of the Fisher King is a parable about the empowering force of friendship and love. One might scoff, calling it a cliché, pointing out that life is far more complex than Arthurian legends transplanted onto the gray sidewalks of New York. But we shouldn’t forget that fairy tales can offer valuable lessons no matter our age. Each of us has our own Grail. The Fisher King warns us not to confuse a mighty artifact with a worthless trinket that may decorate our bookshelf but will never magically fill with water to quench our thirst or soothe our pain when we need it most.