THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA Explained: C.S. Lewis and Religion

C.S. Lewis became famous as the author of the well-known children’s book series The Chronicles of Narnia. However, C.S. Lewis is known not only for creating a fantasy world but also, or perhaps primarily, as a promoter of Christian teachings. Under the influence of his friend J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis transitioned from atheism (a stance he frequently demonstrated, trying to convince his friend of his views) to a deep faith in the early 1930s, after Tolkien persuaded him. After World War II, Lewis became a prominent authority, especially among members of the Anglican Church.

Since Lewis’s conversion played such a significant role, marking every one of his works, it’s worth capturing the pivotal moment when this transformation began (though not into Catholicism, as Tolkien had hoped and worked toward). After all, how could a man who for many years did not grasp the meaning of Jesus’s death so magnificently recreate the essence of that sacrifice, encapsulating it in the act of the rightful ruler of the Narnian land, Aslan? Lewis was perhaps too logical a man to believe in something that defies logic, and yet he came to believe in what he had once categorized as another myth. As he put it:

…myths are lies, though lies infused with sweetness,” said Lewis. “Not at all,” replied Tolkien. Pointing to the wind-tossed branches of the trees in Magdalen Grove, he changed the course of the argument. You call a tree a tree, Tolkien said, and don’t think further about the term. Yet it wasn’t a “tree” until someone gave it that name. You call a star a star and say it’s merely a ball of matter moving along a set course. But that’s just your way of perceiving the star. By naming and describing things, you’re only inventing your own terms for them. And just as language defines objects and ideas, myths define truth. We come to God, Tolkien continued, and the myths we create, although flawed, will inevitably reflect a small, refracted fragment of the real world, the eternal truth that is in God. Only by creating myths, only by becoming a ‘sub-creator’ and inventing stories, can man achieve the perfection he knew before the Fall. Perhaps our myths are mistaken, but they still point toward the true harbor, while materialist “progress” leads only to the yawning abyss and the Iron Crown of evil power. Explaining this belief in the inherent truth of mythology, Tolkien revealed the core of his philosophy as a writer, a belief that lies at the heart of The Silmarillion. (…) Lewis asked, then, whether the story of Christ was a true myth, acting upon us like others, except this myth really happened? Then I’m beginning to understand, said Lewis. (…) Twelve days later, Lewis wrote to his friend Arthur Greeves: “I have just passed from believing in God to a definite belief in Christ—in Christianity. (…) My long night talk with Dyson and Tolkien had a lot to do with it.

Thus… if not for faith and religion, if not for the friendship between Tolkien and Lewis, it is possible that two works so deeply rooted in Christian culture, drawing from the “true myth” and referring to it—namely, The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings—might never have been created. Lewis approached Middle-earth with great enthusiasm, fueling in his friend the sense of calling to bring to life one of the most fantastical, yet truthful, realms ever created in literature. It was Lewis who encouraged Tolkien to work on The Lord of the Rings when Tolkien completely lacked the energy or motivation. Admittedly, Lewis criticized much of it, though Tolkien paid little attention to those critiques and suggestions. Tolkien, on the other hand, did not like the world of Narnia.

“It’s sad,” he wrote in 1964, “that Narnia and all that part of C.S. L’s work remains beyond my understanding, just as he didn’t understand most of my work.” Undoubtedly, Tolkien felt that Lewis somehow borrowed his ideas in his books, and just as he disliked Lewis’s transformation from a converted man into a popular theologian, it may have annoyed him that the friend and critic who had listened to tales of Middle-earth got up from his chair, sat at his desk, took up his pen, and tried writing himself.

Regardless of what Tolkien thought about The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and despite the rivalry between the friends in the literary field, what’s more important is that after moving from the denial of God’s existence to a deep conviction in it, Lewis began writing about this belief, about religion, dealing with theology and creating philosophical essays. Yet his worldview was also present in his fiction. Through his novels, he wanted to introduce Christianity to everyone, acquainting non-believers with it. While his friend used more subtle references, or ones not intended for everyone (as evidenced by the frequent description of The Silmarillion as a difficult and tedious read, an unjust opinion I’ve often encountered), Clive Staples Lewis spoke simply and clearly, avoiding contentious issues, using familiar and understandable examples. Perhaps all the more understandable because they so vividly appeal to the imagination.

We hear that Christ was killed for us, that His death washed away our sins, and that by dying, He conquered death. Here’s the pattern.

And as Lewis writes, patterns bring images closer. One of those images is the book that opens the world of Narnia: The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Everything seems so logically clear, yet hearing comments that this fairy tale is a shallow story for children, one might believe that not everyone understands the simplest allegories. In many instances, biblical images are literally transferred to a world of fairy-tale and mythical creatures, where two sons of Adam and two daughters of Eve are thrown. It’s not an exaggeration to say that Lewis translated the Christian Holy Scripture into the language of fantasy, changing very little while preserving its message, symbolism, and frequently quoting it. Lewis’s conversion thus had a total dimension; it didn’t concern only himself but all his works. Therefore, one cannot separate his faith from his creative output. While Tolkien may have disliked that Lewis became a popular theologian, this does not change the fact that he was one, and how strongly this is revealed in the chronicles, ostensibly designed for the world of children, although, as J.R. Willis notes:

Lewis undoubtedly didn’t have a sentimentality toward children—he said and wrote as much himself.

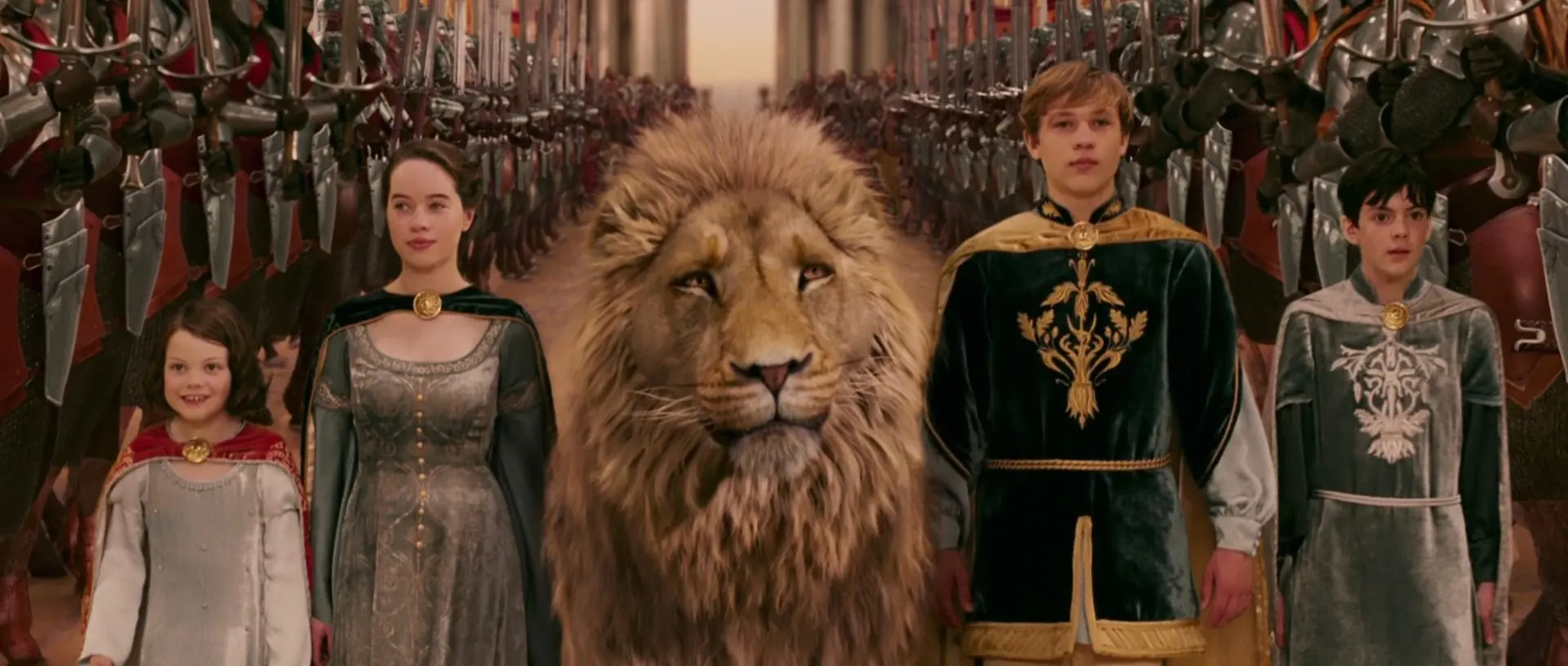

Let us then slowly move on to the film adaptation of The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, which was necessary, as it was essential to translate the well-known story into the contemporary language of technology, providing a chance to meet the reader’s imagination. But how well did Andrew Adamson’s creation handle the challenge it faced? The Chronicles of Narnia is a fairy tale intended for both children, who want to be transported to the most beautiful world full of heroes and the battle of good versus evil, as well as for adults who wish to delve into theological issues presented in an extremely clear and simple way. The adaptation, therefore, was not an easy task, because it could not be an easy one. It’s obvious that time constraints forced the omission of many themes and references used by the author. However, that doesn’t seem to be what’s important, because the film version isn’t supposed to replace the literary original. That’s why I find it much more crucial to ask to what extent it succeeded in portraying Lewis’s ideology/Christian ideology. Did the creators who decided to visualize this story prove to be attentive readers, or did we once again witness the dominance of effects and an overload of battle scenes over the content present in the book?

I won’t delve deeper into theology, as it would be based on the false assumption that I can say anything on the subject, which, of course, would not reflect the truth. Therefore, it seems reasonable to compare Adamson’s film with what the author of The Chronicles of Narnia wrote, especially since Lewis strikes me as more of a promoter of religion, a man who wanted to share what he had come to believe with others, rather than a fantasy writer. The latter seems to have been a byproduct, which seems a valid observation when comparing his style to that of Tolkien. As already mentioned, Tolkien also drew a lot from Christianity, also borrowing from the Bible, changing only the characters’ names, shifting the time, and setting the story in a different place, yet all the while creating something entirely new—a space where the heroes truly live, a world one could immerse in and almost touch. He created an autonomous reality, which doesn’t seem to be Lewis’s main goal, as he doesn’t maintain a balance between these two elements. His characters are not as intricately developed, and their actions can be explained by the same things that explain the biblical examples. Their psychology isn’t as important, as Lewis also references the Bible. His inspirations were so strong that it’s not surprising that he was accused of being somewhat derivative. However, this is justified when we understand that these are images—images that he claimed bring the pattern closer.

In the mid-1940s, there was much talk about Lewis (‘too much for his or anyone’s taste,’ Tolkien said) in connection with his Christian works The Problem of Pain and The Screwtape Letters. Perhaps, watching his friend’s growing fame, Tolkien felt as if the student had quickly surpassed the master, achieving almost undeserved fame. He once referred to Lewis in an unflattering way as ‘theologian for the masses.’

Regardless of whether Tolkien’s comment was meant pejoratively or not, I think it perfectly corresponds to Lewis’s actions. Tolkien simply stated a fact. His friend’s theology was indeed for everyone; it was understandable, and perhaps at times, he treated non-believers in a somewhat childish manner. Yet one cannot deny him logic and simplicity.

C.S. Lewis never sought to enrich Christian thought with his own ideas or impress readers with originality. His sole aim was to present the essence of Christianity clearly, especially for those not initiated into matters of faith.

Thus, the world shown in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a world that—when we enter it with the characters—is engulfed in war. The inhabitants await the coming of the Savior, living in a land covered in ice, where there is no Christmas, no laughter, and where fear reigns under the self-proclaimed ruler, with some creatures giving in and joining her side. This reflects Lewis’s belief that a war is being waged on Earth, a war between good and evil, and one must choose a side—not when it’s over and the sole victor arrives, because that option doesn’t exist. One cannot side with the victor after victory has already been achieved. People must risk and sometimes sacrifice a lot, but they must choose. But why is it that the creatures, waiting for Aslan’s arrival, must suffer? Why does the one who created the world allow evil to spread within it?

Why does God infiltrate the enemy-occupied world and establish something like a secret society to defeat Satan? Why doesn’t He come with force, invade? Is He too weak for that? Well, Christians believe that someday He will come with force—we just don’t know when. But I can guess the reason for the delay. He wants to give us the chance to take His side voluntarily. (…) I wonder whether people who ask God to intervene openly and directly in our affairs realize what that would actually be like. When it happens, it will be the end of the world. When the author walks on stage, the play is over. God will invade; make no mistake about that. But what good will it do you to declare your allegiance to Him then, when you see the whole natural universe melting away like a dream and something else—something never even entered your mind—comes crashing in: something so beautiful to some of us and so terrible to others that no one will have any choice left?

We can witness this event while looking at the film from a broader perspective. The melting of the snow heralds Aslan’s coming, and this event is preceded by the gathering of an army of creatures loyal to him. His return, which takes place after his death, corresponds with the ongoing battle where there are no prisoners, no forgiveness. Evil is destroyed, and the land is enveloped in the most beautiful colors, and the victors are rewarded…

However, it’s no coincidence that the film begins with World War II, outside the fantasy reality of Narnia. This is a real war directly affecting the four siblings and their mother. This family is just one example of thousands of similar families. The father is at war, and the house they’re in is being bombed by the Germans. The children are sent to a peaceful, rural setting—the home of a mysterious professor and his grumpy housekeeper, who decidedly dislikes the siblings. However, the peace is illusory, as the war, which has touched them directly but in which they did not actively participate, serves only as a prelude to what is about to happen and what they will have to engage in. For as it turns out, being chosen ones of the world behind the doors of the old wardrobe in the professor’s house, they will have to defend it if they can find the strength within themselves. And they do. Of course, not immediately and not without dilemmas, but after all, they are children, and being able to believe in a magical world makes it easier for the viewer to believe in their choices, given their age. The land itself seems to represent faith, something for which there is no evidence of existence. However, as the professor says, logic dictates belief when there is no reason not to. One could, of course, ask why a distinctly Christian tale is being told using wartime themes and how the concept of a “just war” aligns with the principle of “thou shalt not kill.” The answer is simple, for Lewis distinguishes between “killing” and “murdering,” does not support pacifism, and believes that there is a just war, and that withdrawing from it would be a much greater mistake than participating in it.

One must remember the Christian belief that people live forever. Therefore, only those little marks or twists in the deepest part of the soul that will ultimately make it a heavenly or hellish being really matter. If necessary, we may kill, but we must not hate or take pleasure in it.