TAXI DRIVER Explained: The Truth Behind Travis Bickle

The profession of a taxi driver can be quite a convenient career path for a serial killer.

Taxi Driver

The profession of a taxi driver can be quite a convenient career path for a serial killer. He is invisible—people usually don’t pay him much attention—and on the other hand, they automatically assume he’s trustworthy. Many treat him like a priest in a confessional or an anonymous bartender, confiding in him about their private matters. The presence of a taxi never raises suspicion; the driver knows the city, the best and quickest escape routes, and isolated places where no one will disturb him—or where it’s easiest to dispose of a body.

David Berkowitz, the “Son of Sam,” was a taxi driver for a significant period. In the summer of 1976 in New York, he killed six people and injured many others. He had excellent knowledge of the city’s layout, often staying one step ahead of the police. It’s worth noting that Berkowitz was a veteran of the Korean War, with an exemplary service record, and was also known as an outstanding sniper. Ultimately, he was caught thanks to… a parking ticket.

Paul Durousseau, also known as The Jacksonville Serial Killer, murdered seven women between 1997 and 2003—two of whom were pregnant. Most of his victims met him while he was driving a taxi for the Gator City Taxi Company, although his criminal activities began earlier. His actions followed a consistent pattern: he gained the trust of his victims, followed them to their homes, broke in, tied them up, raped, and strangled them. In 1992, he joined the army and was stationed in Germany, where local police suspect he killed several women, although this was never proven.

Another example is Christopher Halliwell, a Briton convicted of murdering 22-year-old Sian O’Callaghan in 2011. However, he is suspected of many more crimes, and not without reason: while in prison, he eventually confessed to raping and murdering a woman four years prior to the crime for which he was convicted. He also revealed the location where he had buried Becky Godden-Edwards, who disappeared in 2007. Police simply do not believe that he would have remained inactive for several years. Halliwell was a taxi driver specializing in long-distance fares. There is also the case of Russell Ellwood from New Orleans. He was convicted of murdering Cheryl Lewis, though she was only one of 26 women found dead in the Louisiana swamps between 1991 and 1997. It is estimated that Ellwood may have killed at least 15 of them. He was caught because he could not resist repeatedly driving his taxi to the crime scenes to relive his memories.

For Travis, the taxi is an escape route. He strives to stay as busy as possible around the clock because when he focuses on what he’s doing—driving, the city lights, the passengers who mean little to him but at least fill the void—he doesn’t think and, most importantly, he doesn’t dwell on the past. At the beginning of the film, we see Travis trying to perfect his method of numbing himself: alcohol, long hours of work, pills, or empty sessions in adult cinemas. Even then, however, there’s a ticking time bomb inside him with a delayed fuse. At first glance, he seems cheerful, friendly, and harmless. But every day, by choice, he immerses himself in the dark dealings that play out in the back seat. He observes the filth up close from the perspective of an anonymous, invisible bystander. After all, no one pays attention to the taxi driver.

The Veteran

The desire to become part of the structure of law and order—like the police, FBI, or military—is relatively common in the biographies of serial killers. Sometimes, when they fail psychological evaluations for such roles, they seek substitutes, such as working in security. However, some not only pursued military careers but also participated in wars. The immediate association arises: could the trauma of war have triggered a desire to kill, turning them into monsters?

Closer observation, however, shows this to be an overly simplistic assumption. Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer (at least 71 victims, convicted of killing 49), did serve in Vietnam, but he never saw combat up close, focusing primarily on supply duties. Leonard Lake, who, together with Charles Ng, killed at least 11 people, also never engaged in active combat during two tours in Vietnam, staying mostly near a radio. His partner, Ng, was another ex-marine, though he was discharged from the military in disgrace.

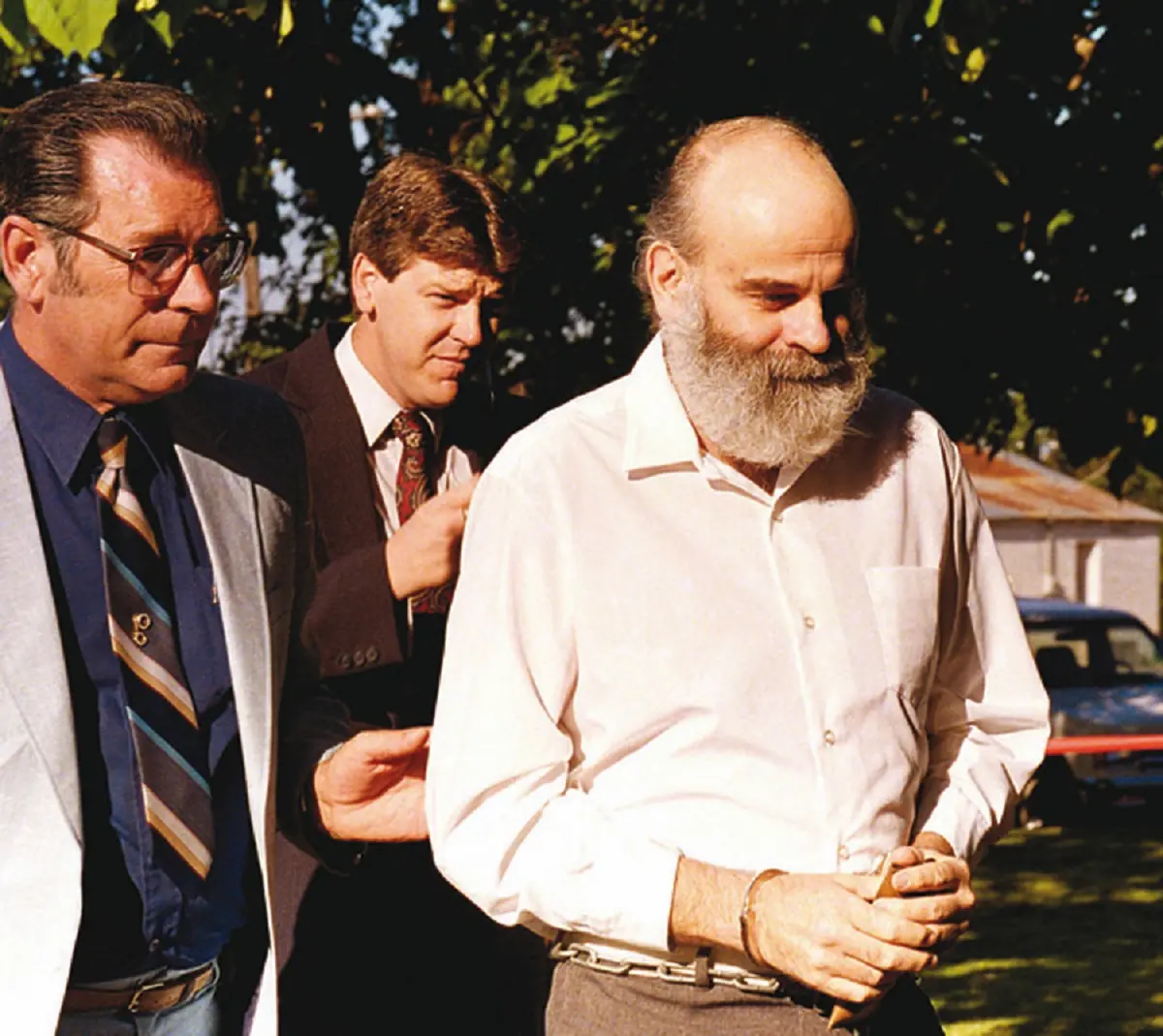

The case of Arthur Shawcross is truly bizarre. If one were to believe his tales, he not only endured horrors in Vietnam but also actively contributed to them, killing women and, under fire, nailing their heads to trees to send a message to the enemy. In reality, he never participated in combat. However, his fabrications already hinted at the man he would become: a brutal murderer who killed 14 people between 1972 and 1989. Roy Norris, in his eagerness to join the Marines, even dropped out of school. Like Shawcross, he never had the chance to wield a weapon in Vietnam. Alongside his partner, Lawrence Bittaker, he earned the nickname The Toolbox Killer. Norris was a ruthless sadist and torturer who inflicted prolonged suffering on his victims before finally letting them die. William Bonin, known as The Freeway Killer—one of several criminals to share this moniker—served in the Air Force during Vietnam and was awarded a medal for his service. He went on to kill at least 21 people, most of whom were hitchhikers.

Lastly, the only individual on this extensive list who actually experienced active combat during the Vietnam War was Ronald Gene Simmons. Simmons spent 21 years in the military, was awarded numerous medals, and retired with the rank of Master Sergeant. Evidence suggests that his lengthy military career, which was the central structure of his life, kept him somewhat in check. After retiring, however, Simmons’ descent was rapid. He sexually abused his daughter, who bore his child, and on Christmas Day in 1987, he systematically murdered his entire family: his wife, five children, his three-year-old granddaughter, and others who arrived for a holiday visit. After the massacre, Simmons went to a bar for a drink, bought a beer, and then returned to sit among the corpses, sipping from the bottle while watching television. A few days later, he visited several locations, including a law office where a woman who had rejected his advances worked. After shooting several people and wounding others, he calmly sat down and chatted with a secretary until the police arrived. He was sentenced to death, and the execution was carried out in 1990.

I’ve mentioned only Vietnam War veterans here, but there are many more instances of military involvement in the lives of killers. However, among them, the percentage of those who actually experienced active combat is very small. Perhaps there’s a certain logic to this—many of these individuals never had the opportunity to “legally” satisfy their violent urges, while their desire to kill only grew, amplifying frustrations. This frustration might be exemplified by Arthur Shawcross’s baseless boasting, indicative of his craving for “real action.”

Cinema has accustomed us to the image of the broken, embittered, and maladjusted Vietnam War veteran, a man for whom there is no place in postwar reality, and whose fragile mental stability is constantly threatened by past trauma. Approximately 2.5 million Americans served in Vietnam. Around 150,000 returned with injuries, often amputated limbs. Twenty-one thousand of them were permanently unable to work. The social and medical support they were offered was far from adequate, and on top of that, they often faced blatant ostracism from segments of society. According to statistics, about 700,000 soldiers came back with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), although it wasn’t widely discussed until 1979. A monthly $200 disability allowance for veterans was hardly a fortune. Many fell into poverty; many turned to crime—within a decade of the war’s end, 25% of Vietnam veterans had been arrested for various reasons. Over 100,000 veterans committed suicide (all figures cited from thevietnamwar.info). The situation began to improve only in the 1980s. These statistics are worth bearing in mind when analyzing the character of Travis Bickle.

As an aside, it’s interesting to note that the term Vietnam Syndrome was used briefly to describe the postwar trauma experienced by veterans. By the late 1970s, however, it had taken on a strictly political meaning, coined by Henry Kissinger and popularized by Ronald Reagan. It referred to the United States’ reluctance to engage in overseas military conflicts. The Vietnam War severely undermined American morale, led to a decline in trust toward the government, and created deep societal divisions. There was a fear that any new military initiative would be seen as “another Vietnam.”

We know very little about Travis’s military service. However, it is certain that he was not one of those who stayed far from the frontlines. There are some differences between Paul Schrader’s original screenplay and Martin Scorsese’s interpretation, which is shown in the film and referenced by the director in interviews. In the original version, Bickle simply “served in the Army” and also mentions a “special mission.” In the film, he is specifically identified as a Marine, and according to Scorsese, he is a member of a special forces unit. This is supported by the knife he carries: a Ka-Bar. However, as the director later explains, he mistakenly assumes that such knives were only used by elite units, whereas they were standard-issue for Marines.

In one scene, a newspaper clipping is visible with the following sentence: Travis Bickle, 26, has been a hack driver for the past six months since he came to New York upon leaving the Services where he fought in a special forces unit in Viet Nam. Film analysts have suggested that Scorsese might have confused Marine special operations forces (United States Marine Corps Special Operations Capable Forces) with Army special forces, also known as the Green Berets (Army Special Forces). This is why Bickle is depicted in the film as a Marine veteran, due to the mentioned mission in the script. However, this is not the most important aspect. What matters is the fact that—again, quoting the director—he experienced life and death every second he was in Southeast Asia… Vietnam affected him, he kept it inside, and eventually it explodes. Although we don’t know the specifics of Travis’s military service, we do know its consequences: ongoing depression, chronic insomnia, recurring headaches, painful stomach issues, and even desperate attempts at self-medication through the consumption of huge amounts of sugar as a temporary mood booster.

Self-Declared Vigilante

The vigilante in film versions is usually surrounded by an aura of righteousness and correctness, his character constructed in such a way that the audience can identify both with him and his mission. In real life, however, the issue is much more complex. Let’s look at a few of the most well-known cases. Perhaps the most famous case is that of Bernhard Goetz, who tabloids often compared to Charles Bronson’s character in Death Wish. In December 1984, Goetz was harassed by a group of young black men in the New York City subway. It just so happened that he had been a victim of a mugging before and, in his opinion, never received the proper justice. This time, he decided to take matters into his own hands. He pulled out a gun and fired five shots. The worst happened to Darrell Cabey: after the first shot, Goetz commented, “you don’t look so bad, you’ve got one more.” All four of the supposed assailants survived, but Cabey was permanently paralyzed. The case of Goetz, dubbed the “Subway Vigilante” by the press, sparked much controversy, mainly due to the race of those involved and the verdict Goetz received: eight months for possession of an unregistered firearm. It was also never conclusively determined whether he was actually mugged or simply misinterpreted the situation.

When considering approval of a vigilante stance, there are a few things to keep in mind that may not be relevant from the film’s perspective: on screen, we watch the motif of revenge with enjoyment, and it has a cathartic effect—the justice has been done, even though the system failed, so we’re not entirely defenseless. This increases our sense of strength and gives a specific feeling of comfort. The lone avenger is vigilant, and we are safe because someone is on our side. In real life, however, catastrophic mistakes can occur—such as the one made by Gary Sellers and Robert Bell, who wanted to drive a man convicted of possessing child pornography out of their neighborhood. They set his house on fire. The actual target of their vengeance was rescued from the flames, but his wife, an entirely innocent woman, tragically died.

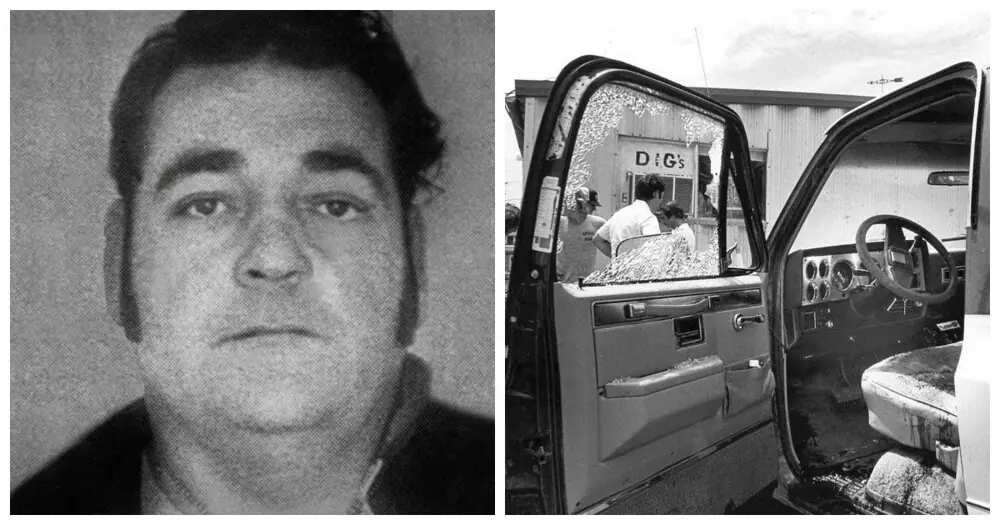

The second issue: when we respond to violence with violence, taking a human life, do we not, in fact, become similar to the person we seek to punish? Let’s look at the case of Ken McElroy. In the small town of Skidmore, Missouri, everyone was afraid of him. Every time he was jailed, he quickly got out, as he was excellent at intimidating witnesses. In 1973, a fourteen-year-old girl became pregnant by him. He showed no remorse for his heavy hand with her or the child. In 1980, he killed an elderly shopkeeper. And again, he avoided punishment by posting bail. In 1981, someone finally decided to put an end to this. Almost fifty people witnessed McElroy’s death, as he was shot in his own truck. No one called for an ambulance, even though McElroy’s wife was also in the truck. Later, no one remembered anything. His wife described the attacker, but no one corroborated her story. To this day, a code of silence prevails in the town.

And finally, the third problem: the escalation of violence through more violence. This is especially visible when the mob takes control. A mob, after all, sweeps away everything in its path, often committing mistakes along the way. In 1915, Leo Frank was lynched, but a few years later, he was proven to be innocent. In 2013, when the victim of a rape committed by Santos Ramos died in Bolivia, a mob of two hundred people dragged him to her open grave during the funeral and buried him alive. In the late 1950s, Mack Parker, accused of raping a white woman, had only an uncertain identification from a distressed victim as evidence against him. He was in jail when a vengeful mob appeared outside the prison. They didn’t have to break in by force; the sheriff dutifully opened the cell doors for them. Parker was bound with chains and thrown into the river. It wasn’t until 2009 that efforts were made to prove his innocence and clear his name.

No, a vigilante acting freely is by no means a guarantee of law and order. And, despite everything, it is not a guarantee of justice either. Travis’s anger is not directed at a particular individual. It is a rage aimed at the entire city, the entire country, the whole system. In his understanding, there is no one willing to take on the task of cleaning up the pervasive filth and eradicating it once and for all. Most of all, the people most suited for this task—the ones in power—are the least likely to do it. At the core of Travis’s actions lies a deep sense of betrayal. The world has failed him; people have failed him. He has been used, chewed up, spat out, and forgotten. Yet, he still needs something to fight for, something to give him purpose. No one is coming to help him, so he finds that purpose himself, transforming into an anonymous vigilante, a near-mythical figure emerging from the darkness.

Travis Bickle

Travis’s motivations are loosely based on the story of a certain Arthur Bremer – he also kept meticulous journal entries. In 1972, Bremer attempted to assassinate Governor George Wallace, also wounding three bystanders. Wallace himself was paralyzed from the waist down. Bremer’s life was dull, but not particularly dramatic – he was capable, could have studied and had a future. However, he was unable to connect with his peers and as a result suffered from social isolation. As a result, he did not mature emotionally enough, and this contributed to the breakdown of his brief relationship with sixteen-year-old Joan Pimrich. Joan resented his constant sexual innuendos and his penchant for shocking her with pornographic photos, and she felt embarrassed when he failed to behave appropriately in public. After they split up, Bremer stalked Joan, calling and following her, and eventually shaved his head to reflect the “emotional emptiness” he was experiencing. After Bremer’s arrest, Joan publicly expressed her astonishment, declaring that he had never been violent and had no interest in politics. Bremer simply wanted to do something spectacular at last, so that no one would dare to disrespect and ridicule him any more.

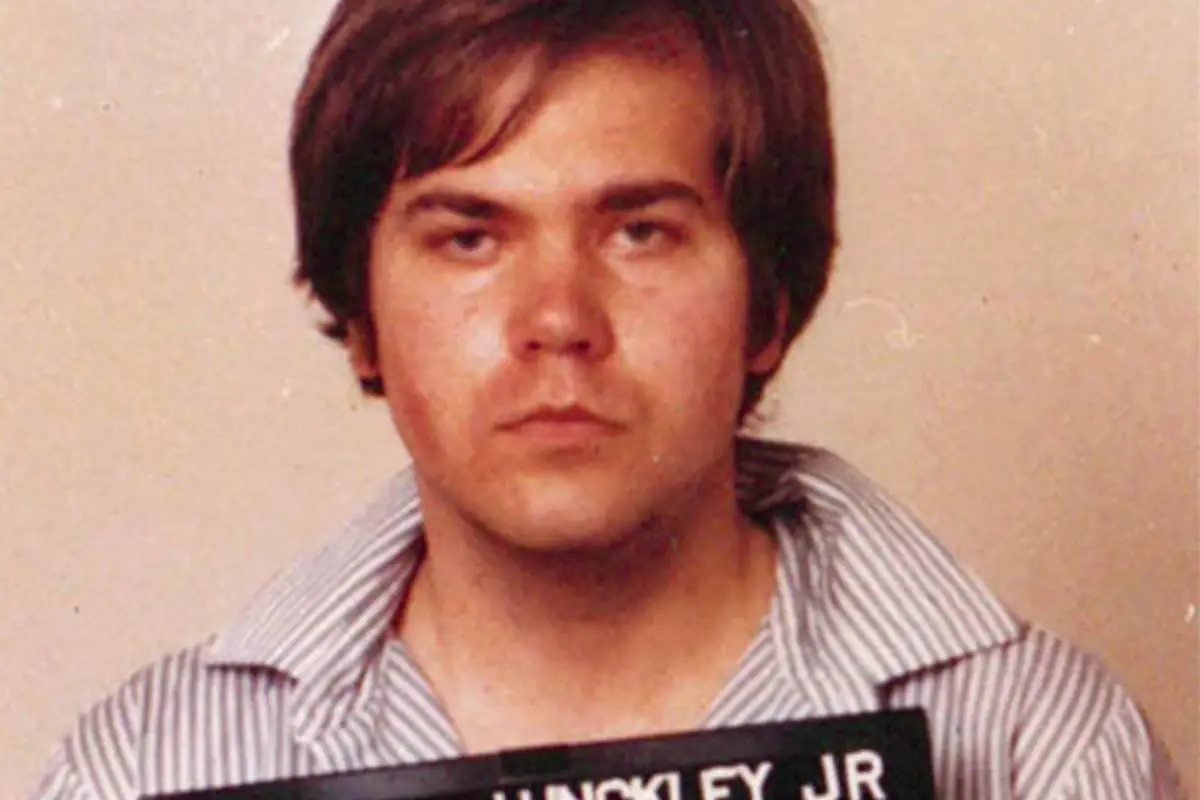

When Taxi Driver hit the screens, John Hinckley Jr. became obsessed with the film, particularly with Jodie Foster, who starred in it. He repeatedly tried to contact her, even enrolling in courses at Yale, where she was studying at the time. He left her notes and poems under her door, all to no avail. He then began fantasizing about something more dramatic: hijacking an airplane, committing suicide in front of her… Eventually, he realized that his beloved movie was the best source of inspiration! While he wasn’t particularly interested in politics, he thought that by assassinating the president, he would permanently etch himself into history, thus gaining significance equal to that of Jodie Foster. After the 1981 assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan—where the president barely escaped with his life—Hinckley was committed to a psychiatric institution, from which he was released in September 2016. He is reportedly cured and no longer poses a threat.

Travis’s motivations seem to be more global and less tied to his own personal struggles than those of Bremer or Hinckley. Travis seeks purity, he’s on a quest for it. He yearns to witness firsthand, with his own eyes, that there might still be something perfectly innocent in this repulsive, corrupted world. When he first notices Betsy in the crowd, he feels as though he has encountered an angel, an ideal that nothing can tarnish. He wants to be near her and immerse himself in her beauty, something he makes no effort to hide during their first encounter.

So why, for heaven’s sake, did he take her to an adult movie on their second date?!

There may be two reasons for this, and it’s possible that both are valid. First, Travis is clearly socially unadapted. He struggles with understanding what is appropriate, what is socially acceptable. His humor is rather esoteric, his knowledge of popular culture and social events is minimal. He is not a master of light conversation and often makes social blunders, misjudging the situation. Secondly, as indicated in his monologue during his encounter with presidential candidate Senator Palantine (“The president should clean up this city…”), Travis is slowly beginning to formulate his manifesto. Although he consciously denies this, on a subconscious level, he starts to believe that everything around him is tainted and susceptible to corruption, including himself and the angelic Betsy.

His aggression grows, his anger slowly reaches a critical point. He is on a collision course that leads to destruction—but also to self-destruction. In other words, Travis sabotages what could have been life-affirming, good, and promising in his life. Although he has not yet taken action, he has already crossed the line from which he cannot retreat. He tries to defend himself, but Betsy rejects his attempts to clear the air. In doing so, Bickle only confirms his belief: she is just like everyone else. Exactly the same. He finds no understanding from his friend either, for “everything will be fine” is not good advice, but rather a sign of complete disregard. The last straw breaks. Travis embarks on his crusade.

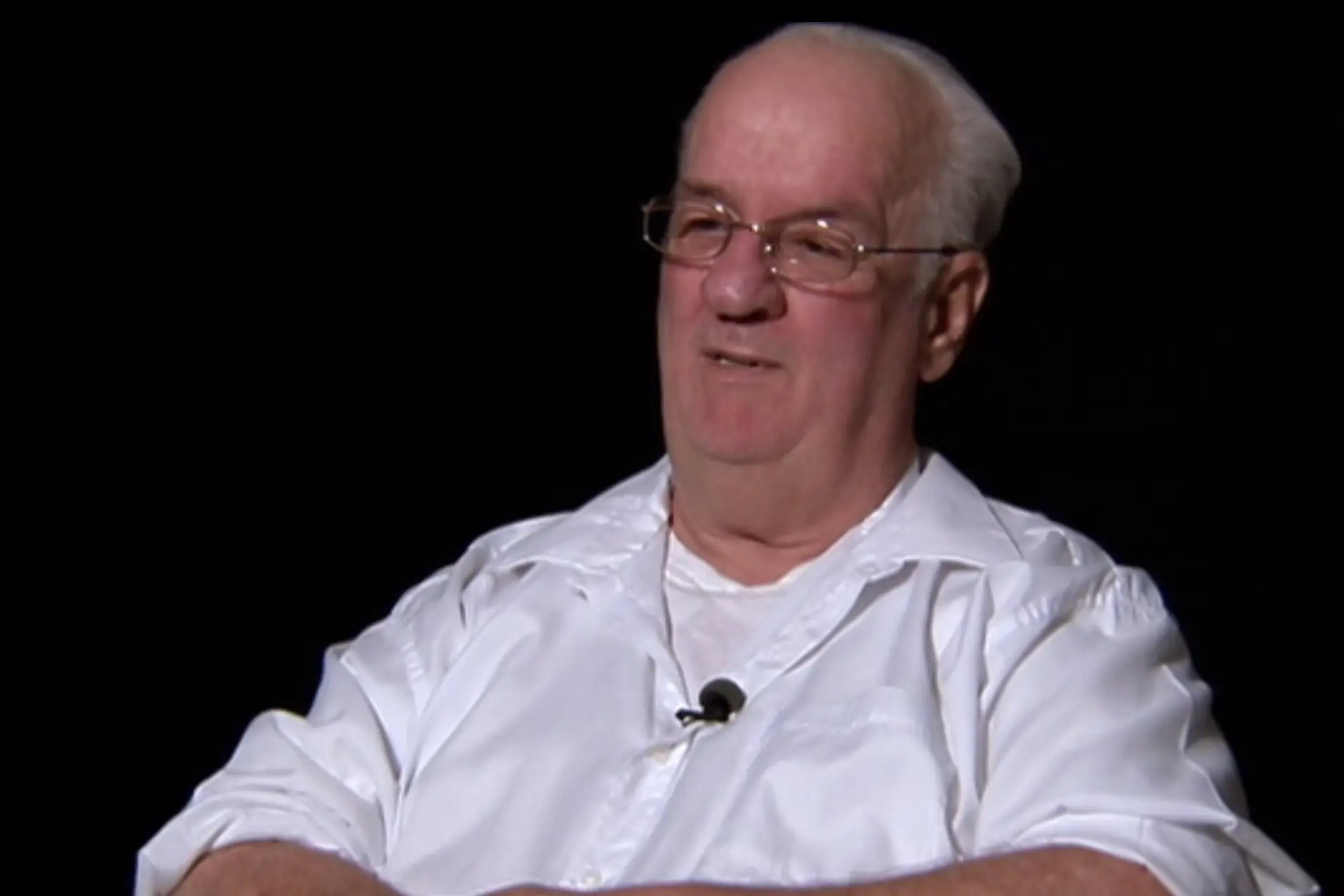

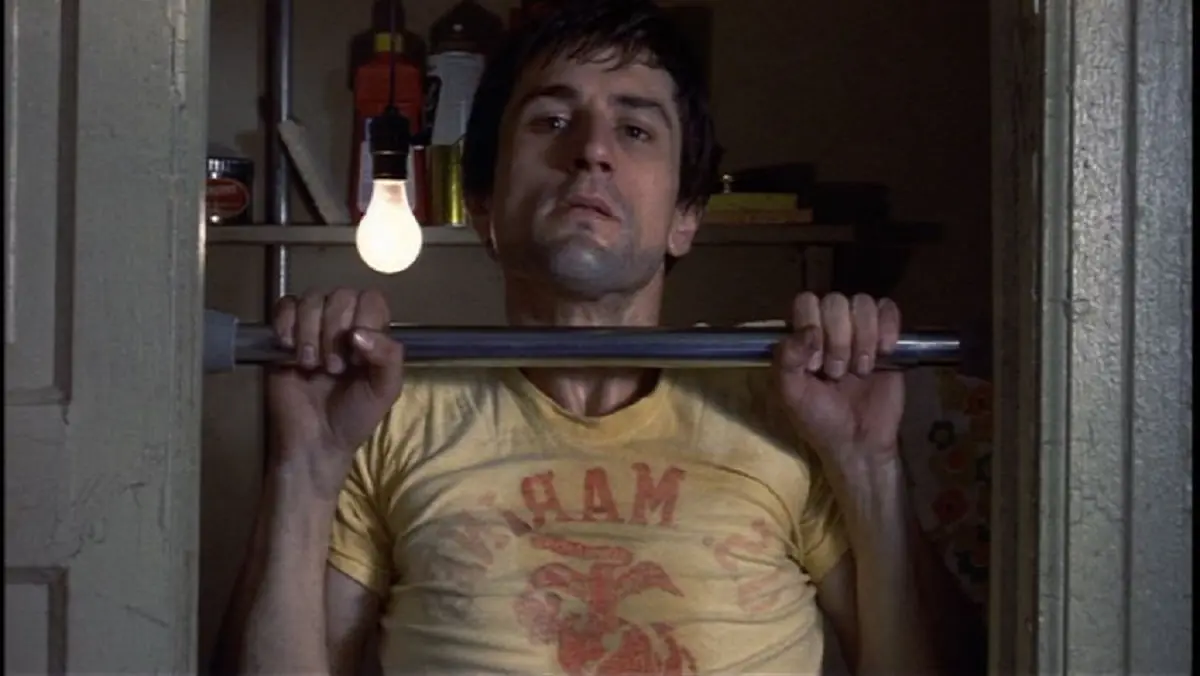

This is where the most famous sequences of the film begin: working on his fitness, buying a gun, shaving his head into a mohawk, and the absolutely iconic You talkin’ to me?. At this point, Travis’s only partner is himself. Like every human being, whether they want it or not, a social being, Bickle desires to be part of a group, to interact with others. He sees these interactions all around him, and, in fact, they often provoke in him disgust and opposition. Yet, he remains on the outside, and this hurts him. Created for loneliness, always alone—God’s Lonely Man.

Paradoxically, during this period, he is in a much better mood, calmer, and more content than he has been in months. This is somewhat of a suicide syndrome: once the decision has been made, those planning such a desperate act relax and feel truly good. That’s why, afterward, their loved ones are often so shocked: everything seemed fine, how could it be? Travis accepts that he has set off on a suicide mission. Perhaps he even desires it. In this “preparatory” period, the character of Iris becomes crucial for Travis. She is a young prostitute who is ruthlessly exploited by her pimp, Sport. To say that Iris “saved” Bickle from himself, leading him off the dangerous path and giving him a new, noble purpose, would be an exaggeration. Blind fate and chance had more influence here.

Nevertheless, she is important to him. Above all, he sees in her the innocence and purity he’s searching for, still present despite the filth she lives in every day. There is also a chance she might be able to preserve it, of course, if she manages to escape. Otherwise, the machine will eventually grind her up and leave behind a broken human being. Travis remembers Iris well because she came so close to asking for his help that night when, fleeing from Sport, she jumped into his taxi. Of course, she didn’t, but she noticed him. He was her chance, and at that moment, he was important to her. He wants to be important to her, because he just wants to be important to someone. He has forgotten what it’s like to be disregarded after so long. And she listens to his words. Maybe his arguments reach her with delay, but they do reach her. She thought about what he said, it mattered to her. For this reason alone, she is worth saving, even if it’s against her will. And so, thanks to fate’s hand and Iris, Travis Bickle transforms from an assassin into a hero.

Some critics have found a deeper meaning in the final five minutes of the film, speculating whether the outburst of praise for Travis, his newfound hero status in the eyes of the public, and even his reconciliation with Betsy might, in fact, be a deathbed fantasy of a fading mind. For others, it is an ironic twist of fate that a vigilante, filled with such disdain for the world, becomes the city’s favorite, while it was only a hair’s breadth away from him becoming the public enemy number one, like John Hinckley Jr. or Lee Harvey Oswald.

According to Scorsese and Schrader, the intention was different. This is reality, not a dream, but the point is that Bickle has not been healed. His heroic act did not bring him to clearer waters, did not heal his wounds, nor fix the situation. He remains a ticking time bomb, one that will sooner or later explode, and so it will continue endlessly, eventually leading to his self-destruction. This outpouring of approving enthusiasm is, for Travis, just proof that something is very, very wrong with this city. The final scene, Schrader says, symbolizes the rewinding of the film to its beginning. Travis starts at zero and moves toward the same conclusions and the same actions. Again and again. Such is the fate of someone who calls himself God’s Lonely Man.