THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS Decoded: Fascinating Evil

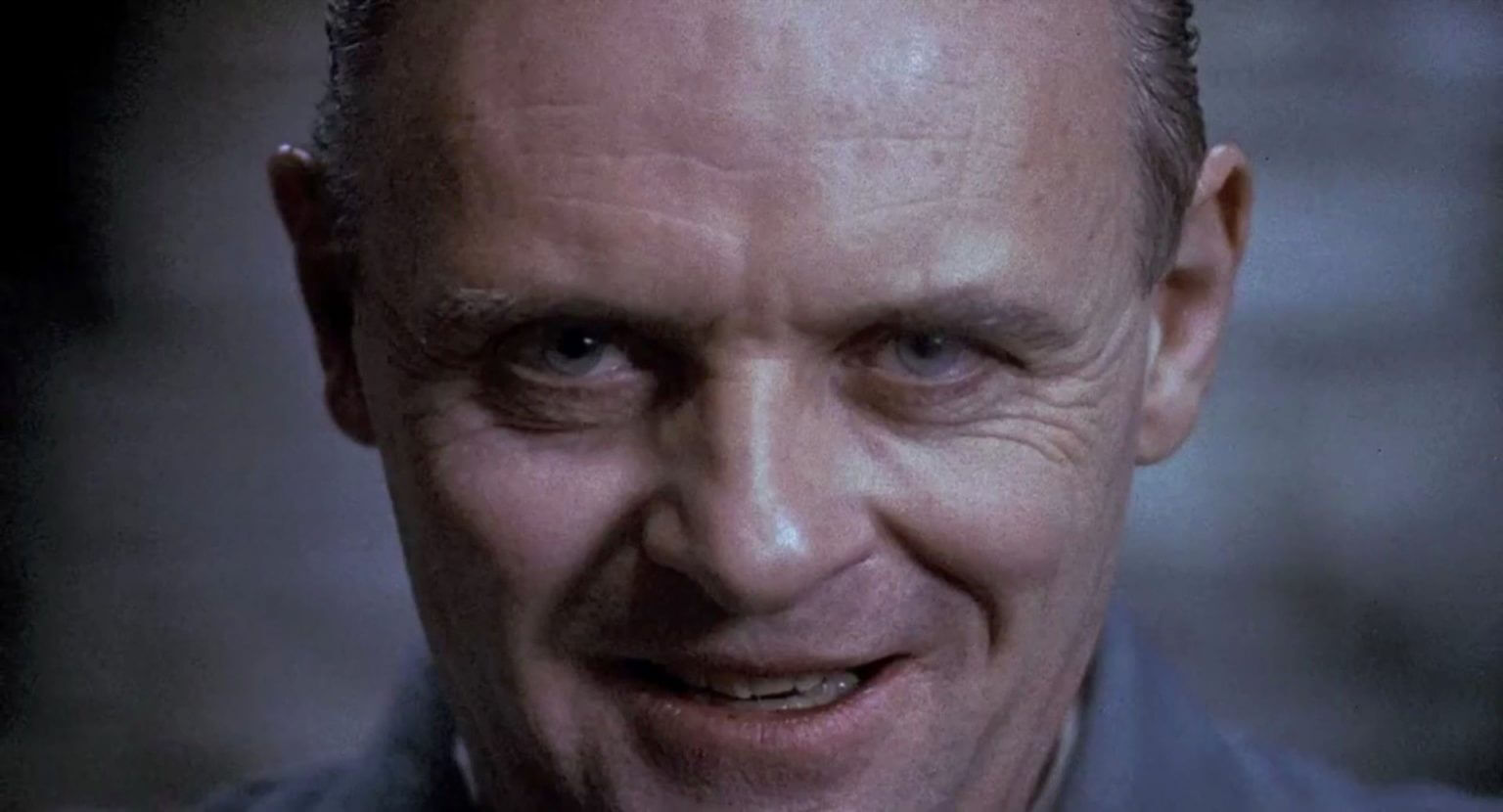

…as convincingly as Anthony Hopkins did in portraying Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. His charisma, his cold, piercing gaze, the restrained elegance in his movements—everything about him inspires terror.

He embodies murderous ruthlessness, an archetype of evil, and yet it is impossible not to feel admiration and awe for the power of his mind. And that is the most frightening part. We may try to rationalize, for peace of mind, that this admiration stems from regret that such qualities of spirit and intellect are tainted, depraved, and ultimately wasted. Yet it’s hard to escape the awareness that corruption and depravity are essential for them to function so effectively.

As we all remember, Lecter despised being pigeonholed. He loathed the convenient schemas of psychiatric classifications because he never fully fit into any of them. The naïve researcher armed with a questionnaire was treated in a purely… culinary fashion. Clarice sees this clearly, despite her youth and inexperience. Is he some kind of vampire? one curious policeman asks. There is no name for what he is, Clarice replies.

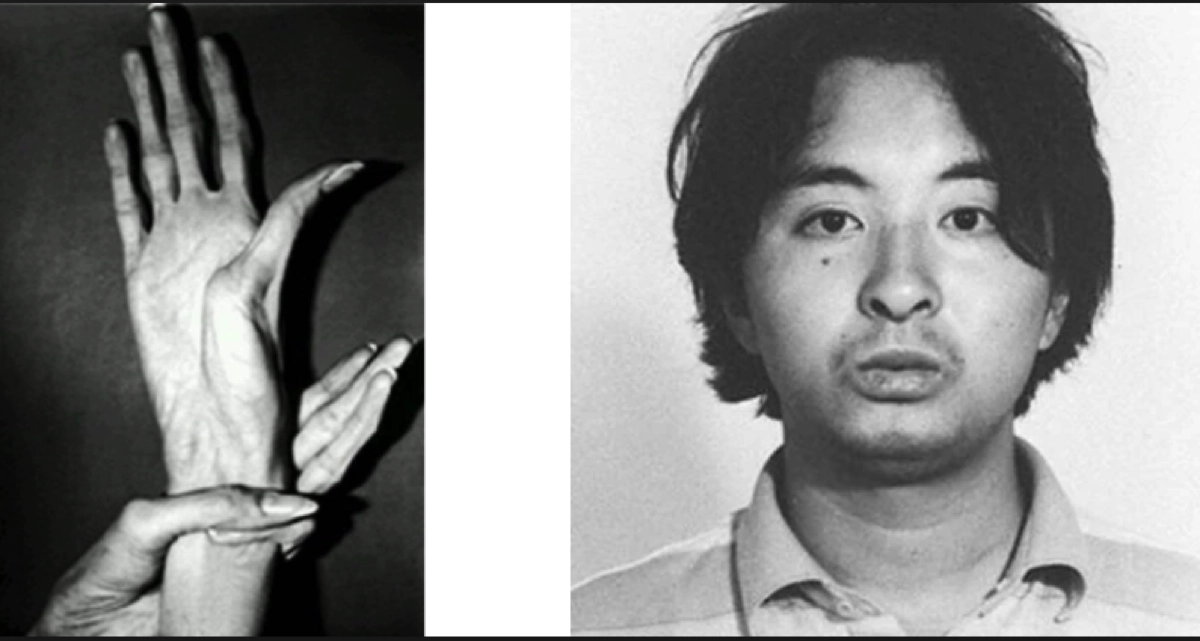

A psychopath. A narcissist. A sadist. A cannibal. How inadequate these labels seem when applied to Lecter is most evident when compared to real-life murderers who, over the years, were speculated to have inspired Thomas Harris directly. The names Albert Fish and Tsutomu Miyazaki were the most frequently mentioned. Heaven only knows why, as both were cannibals, yes, but also pedophiles and necrophiles, with Fish additionally being a masochist.

Miyazaki, plagued by a grotesquely exaggerated inferiority complex due to his deformed hands, murdered four girls aged four to seven between 1988 and 1989. He drank their blood and desecrated their corpses, keeping severed body parts—especially hands—as mementos. During his trial, he insisted the murders were committed by his alter ego, which he called the “Rat Man.” He drew dozens of mini-comics featuring the “Rat Man” as the protagonist, and his obsession with anime (he was even dubbed The Otaku Killer, referencing the term for those obsessed with Japanese pop culture) sparked considerable controversy in Japan. Miyazaki’s collection included 5,763 video cassettes, mainly anime and slashers. He was hanged in 2008.

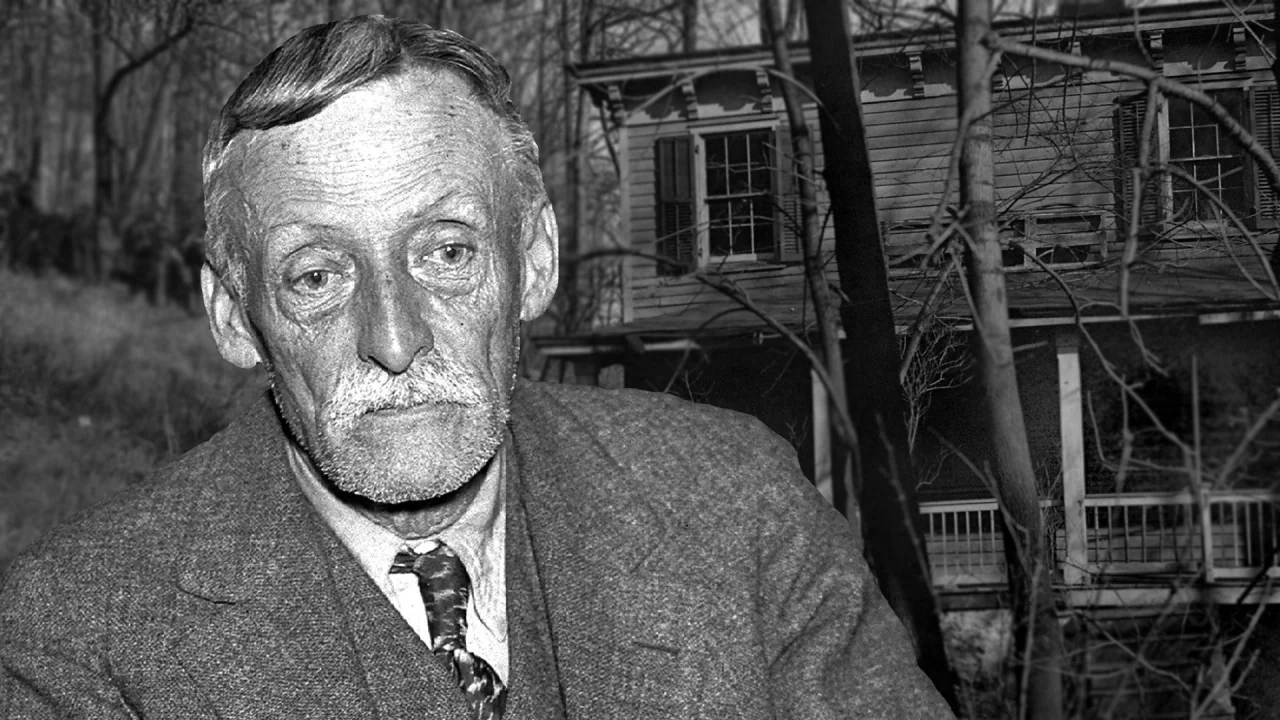

Albert Fish, meanwhile, was an avowed sexual deviant for whom no paraphilia seemed too revolting, including coprophagia. He met his end in the electric chair in 1936.

Hannibal Lecter would likely have been disgusted by both Miyazaki’s weakness and Fish’s lack of self-control. He would, in all probability, have dismissed such behavior as a “lack of manners.” The true inspiration for Lecter’s character, however, was revealed relatively recently, on the 25th anniversary of the publication of The Silence of the Lambs. It traces back to Thomas Harris’s time as a reporter in Mexico, where he encountered someone he referred to as Dr. Salazar.

Dr. Alfredo Ballí Treviño was sentenced to death for murdering his partner, Jesús Castillo Rangel. His sentence was later commuted to 20 years in prison. While incarcerated, he earned significant respect, providing medical care and even performing minor surgical procedures. Harris recalled his cool elegance and dignified demeanor. After his release, Dr. Ballí married, had children, welcomed grandchildren, and continued practicing medicine for the rest of his life, primarily serving the poor for a nominal fee. He passed away from prostate cancer in 2009.

It’s said that Dr. Ballí always knew he had served as inspiration for the writer; his family even jokingly called him “Dr. Lecter,” a nickname he reportedly found amusing. There were suspicions that Jesús Rangel was not his only victim, but no further crimes could ever be proven against Salazar.

So how can we approach Lecter without falling into the trap of simplistic and convenient categories? The simplest way is to use a mental exercise. Let us imagine ourselves as Agent Clarice Starling. An ambitious student with a sorrowful past, orphaned early—first by her mother, then by her beloved father. A young woman who realized very early on that, despite the best intentions, it is impossible to save the whole world. That sometimes even saving a single individual is too difficult. She fights with all her might to carve out a place for herself in a world dominated by men, putting in maximum effort and giving her all. Haunted by the recurring thought that even her best might not be enough. She is full of admiration for the intellect and knowledge of her superior and mentor, Jack Crawford. Clarice has not yet learned how to pretend, which is what makes her so attractive to Dr. Lecter. She is a blank canvas upon which he can paint.

So here we are, stepping into Clarice’s shoes, given our first serious opportunity in our budding career—a chance to speak directly with a man as depraved as he is brilliant. What are we thinking? Above all, we desperately want to prove that we’re the right person for the job, that we won’t fail. We’re scared out of our minds, especially since Crawford himself has warned us not to let Lecter into our head. But on the other hand, we don’t fully understand what that might entail. Here, inexperience and a kind of youthful bravado come to our aid. Where others have faltered, we’re determined to succeed.

It’s an ironic twist of fate because this meeting with the terrifying Hannibal the Cannibal—a man whose heart rate never rose above 85, even while swallowing the tongue of the nurse attending to him—is, for us, let’s be honest, a dream come true. A massive career opportunity. So, we walk down the corridor of isolation cells, trying our best to project professionalism in our neatly pressed suit and cheap shoes. We can’t afford better, but our strength, after all, lies in our mind. We push forward, pretending not to notice the vulgar words hurled our way by Miggs. And then, we come face to face with the man who, despite the confines of his cell and the thick layers of armored glass, sees all our efforts—and their origins—as plainly as if they were written on our skin. It is not a pleasant experience. Clarice herself paid for it with spasms of tears, because that’s often how we react when all our protective barriers are suddenly stripped away, leaving us to confront our shadow, raw and unfiltered. This meeting could have been the last, but instead, it became the first.

And, let’s be honest—it flattered us. Even if we’d never dare admit it.

And Hannibal Lecter?

At first, he is mostly amused

What should theoretically insult him—that Jack Crawford sent him a student—actually entertains him immensely. “He must be that desperate!” Lecter thinks with visible delight. The temptation to mock the all-powerful Crawford is so irresistible that Lecter cannot pass up the promise of amusement. He knows how much Clarice admires Crawford, and stepping into the role of her mentor is child’s play for him—a role he takes on without hesitation.

With a few deft sentences, he dissects Clarice’s most hidden and painful secrets and administers a small test of honesty, which Clarice passes. He repeats the humiliating line Miggs directed at her. And she responds with politeness—extreme politeness. After eight years of confinement, Hannibal Lecter has few genuine sources of entertainment. His mind craves stimulation and finds little in his sterile surroundings. Clarice provides him with his first real intrigue in years. Miggs loses his life in the process, but honestly, it’s no great loss to society. The prospect of further amusement is so enticing that Lecter decides to grant Clarice more chances.

Point One: Hannibal Lecter enjoys playing games

Because Dr. Lecter is so perfectly composed, charming, and impeccably polite, his deliberate vulgarity has twice the impact. What might pass unnoticed from the mouth of an ordinary street ruffian stands out starkly when it comes from him. It’s an excellent opportunity to test Clarice’s boundaries. Can she be provoked, or can’t she? Because if she can be provoked, then, as much as it might disappoint him, she isn’t worth the effort.

But she doesn’t falter. She withstands the attack, and at that moment, Lecter begins to see her not as a pawn sent by Crawford but as an individual worth examining under his magnifying glass.

Point Two: Hannibal Lecter is an observer

He belongs to that rare breed of individuals who, even when they already know the answer to a question, cannot resist the urge to ask it anyway. He enjoys games—in all their forms, from subtle manipulation to classic anagrams—but he only engages in such games once his conversational partner has earned a certain degree of respect or, at the very least, his attention. This is why he has no interest in toying with Dr. Chilton and quickly grows bored with Senator Martin.

A typical psychopath is often a master of feigning emotions they neither feel nor understand, doing so purely for personal gain. Lecter operates in a similar fashion, but the act of pretending has long since wearied him. Instead, he adopts a veneer of sincerity, stretching the boundaries of honesty just enough that someone like Clarice can begin to discern the difference between truth and theater. The solution to the mystery of Jame Gumb is clear to Lecter from the start. But where’s the enjoyment in solving the puzzle outright? Where’s the pleasure in playing an intricate chess match without advancing through the steps, move by move? The fate of Buffalo Bill’s potential victims, of course, doesn’t concern Lecter in the slightest. What does interest him is what he can gain for himself.

He has no illusions about the delightfully absurd promises of reduced prison restrictions or beach strolls under SWAT surveillance. However, he rightly sees an opportunity in persuading desperate players to engage in a charade. The charade necessitates a new strategy, a break from routine. And in any deviation from routine, all it takes is one loose link—a moment of desperation—to create the opportunity Lecter needs.

Point Three: Hannibal Lecter is a strategist

“Quid pro quo,” Lecter says to Clarice. Something for something. He will provide information, but only if she offers something in return. He is utterly unmoved by pleas for urgency, by the desperate hope for mercy on behalf of the kidnapped Catherine Martin. Such considerations are irrelevant to him. By this point, Lecter is focused solely on the opportunity to reclaim his freedom. Most people would falter under such circumstances, let their guard down, or act impulsively. Not Lecter. Ever the picture of composure, he continues to play his game with Clarice at its center.

He knows, and she knows too, that an uneasy connection has formed between them—a kind of alliance: us versus them. From the start, Lecter deliberately fosters in Clarice the belief that she understands him better than others, that she can reach him, and perhaps even outwit him. For Lecter, this is the only kind of intimacy available in his situation, and he seizes it without hesitation.

What attracts him to Starling isn’t her femininity, contrary to the misguided assumptions of the chauvinistic Chilton. It’s her pain—raw, unvarnished, and deeply human. The more genuine it is, the more it captivates him. Lecter values this authenticity above all else. While he appreciates manipulative skill as an art, he has no tolerance for outright lies. Clarice would lose all credibility with him if she tried to distort or sugarcoat her emotions. Yet, he is forgiving of her minor transgressions—like the embellished promises of beach walks and island escapes—because they serve the broader strategy.

For Lecter, sincerity is not just a moral preference but a tactical advantage. He understands that Clarice’s unflinching honesty makes her an exceptional opponent and a worthy collaborator in his intricate mental chess game.

Point Four: Hannibal Lecter is an absolute control fanatic

Lecter’s obsession with control extends beyond his environment to encompass himself entirely. For him, losing control equates to weakness, and weakness leads to mistakes, which he abhors as the ultimate form of sloppiness. In this aspect, Lecter refuses to take shortcuts. His control begins with rigorous self-discipline—he is not merely trained but meticulously conditioned to perfection. Every facet of his being that could be honed has been sharpened to its utmost potential: his senses, memory, artistic talents, posture, economy of movement, facial expressions, even the modulation of his voice. Lecter is a man who embodies complete mastery over himself, relying solely on his abilities.

This self-command extends to his primal instincts—the urge to kill and consume his victims. Lecter doesn’t deny himself these urges, but he ensures that he indulges them only on his terms. In this, he distinguishes himself from the majority of compulsive killers. He belongs to a rare category of predators who, theoretically, could refrain from killing if they chose to. For Lecter, it’s not a matter of necessity but of volition. And Clarice Starling, in her unique way, becomes the ultimate proof of his restraint. Her presence reaffirms his dominance—not over her per se but over his impulses. She embodies the guarantee of his strength.

Lecter’s acts of cannibalism, as depicted in The Silence of the Lambs, are not impulsive or chaotic but rather calculated and ritualistic. For him, consuming another person represents the ultimate assertion of power over their being. It’s an act steeped in symbolism and ceremony, requiring the utmost precision and respect for his own standards. As a psychiatrist, Lecter’s expertise lies in peeling back the layers of his subjects’ minds, exposing their vulnerabilities, and asserting dominance over them. His killings are the final, irrevocable culmination of this control, performed entirely on his terms.

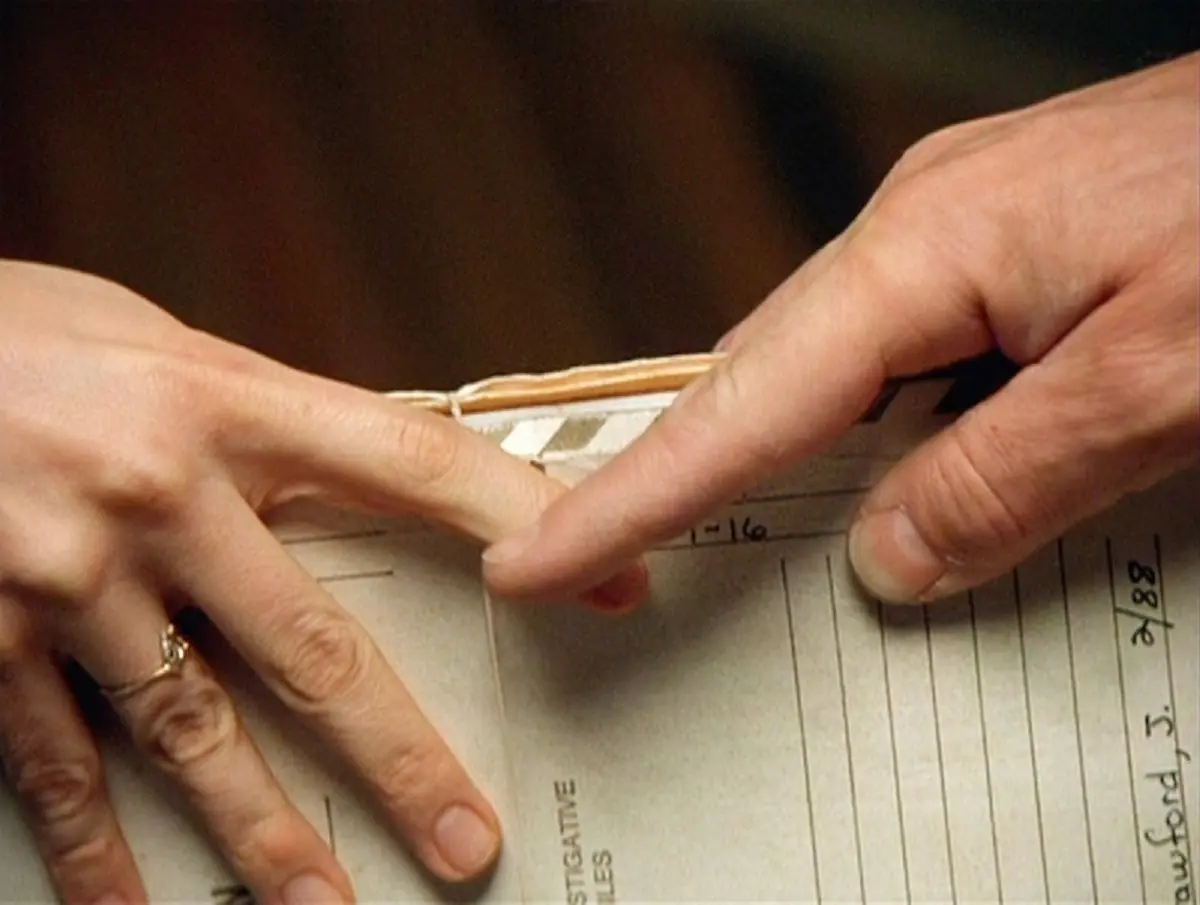

Take, for example, the scene where Clarice, defying protocol and safety measures, rushes back to Lecter’s cell to retrieve the Buffalo Bill case file. Lecter lightly grazes her finger with his own as he hands over the documents. This subtle gesture is charged with eroticism, but more importantly, it is an unambiguous declaration of control. It signifies Lecter’s dominance—not just over Clarice but over himself. This fleeting touch seals their unspoken pact. It’s a bond forged in mutual recognition and cemented by Lecter’s unwavering command over his actions and his environment.

Point five: Hannibal Lecter is an aesthete

Lecter’s aesthetic sensibilities transcend conventional notions of beauty. For him, aesthetic value lies in the extraordinary, in experiences of such intensity and depth that they evoke a visceral, transformative response. Beauty, to Lecter, is relative—it must be ecstatic and profound to hold meaning. This could manifest in the melancholic splendor of Florence’s Duomo at dusk, the exquisite taste of tears, the primal terror captured in a lamb’s scream, the orchestral mastery of a genius conductor, or even the visceral, hypnotic flow of blood from a vein. For Lecter, anything that resonates with authentic intensity and truth qualifies as beautiful.

Consider his extraordinary sense of smell, an ability so finely tuned that it bypasses simple dichotomies of pleasant versus unpleasant. Scents, to Lecter, are narratives, laden with significance or emptiness. Similarly, his eidetic memory operates on this principle. A mind like his, endowed with perfect recall, cannot discard experiences but must instead find ways to derive meaning from both the cherished and the grotesque. The coexistence of these memories shapes his appreciation for life’s dualities—its highs and lows, its delights and horrors.

For Lecter, this heightened sensitivity becomes his guiding principle. His aesthetic is one of dual extremes: the sublime and the macabre, the divine and the destructive. He seeks to distill the essence of every moment, no matter how unsettling, into something profound. Beauty, for Lecter, lies not in the superficial or the expected but in the raw, unfiltered experience of life and its inexhaustible complexities.

Point six: Hannibal Lecter understands and appreciates the mechanism of emotions

A person with as complex a worldview as Lecter, and with equally vast horizons, is incapable of denying emotions as such or their role in fully experiencing the complexity of phenomena and, in turn, their beauty. And Lecter would never deny himself the experience, understanding, curiosity, or knowledge that comes from it.

For him, feeling is an abstraction, but analysis and comprehension are not. Just as a person without legs learns to use prosthetics, Lecter gathers knowledge about feeling, emotions, and their wide spectrum, somewhat per procura – practicing as a psychiatrist. The intricacies and complexity of feelings are well known to him; in fact, he knows more about them than the average person, and he never has enough of that knowledge. He collects it eagerly like an experienced scientist, and if he chooses to, he can use it, even if, just like a prosthesis for someone disabled, it is an external construct for him, fundamentally foreign.

In his pursuit of perfection, he is fearless. Likely, if asked, he would respond that understanding emotions and implementing them is a more perfect form than the flawed, inherently error-prone experience. Observing from the outside provides satisfaction and knowledge. Looking from within – so much confusion. And usually, sooner or later, pain.