Movies Inspired by the True Murder Case of Leopold and Loeb

It was 1924, and the nature of this particular crime deeply shocked public opinion for at least several reasons.

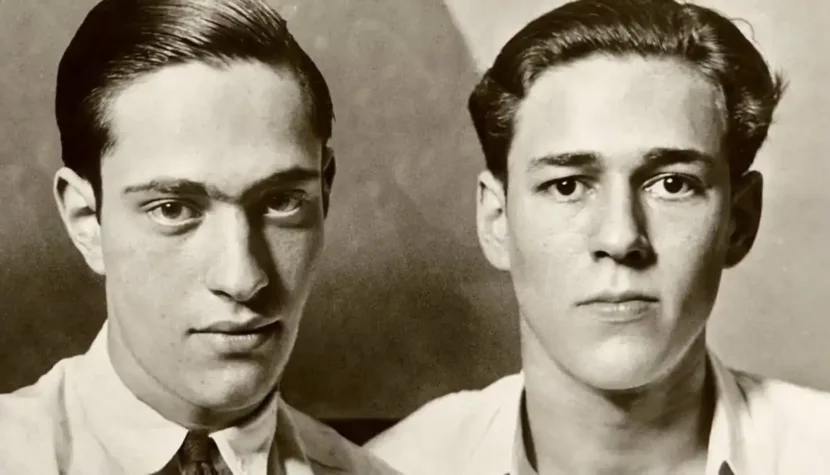

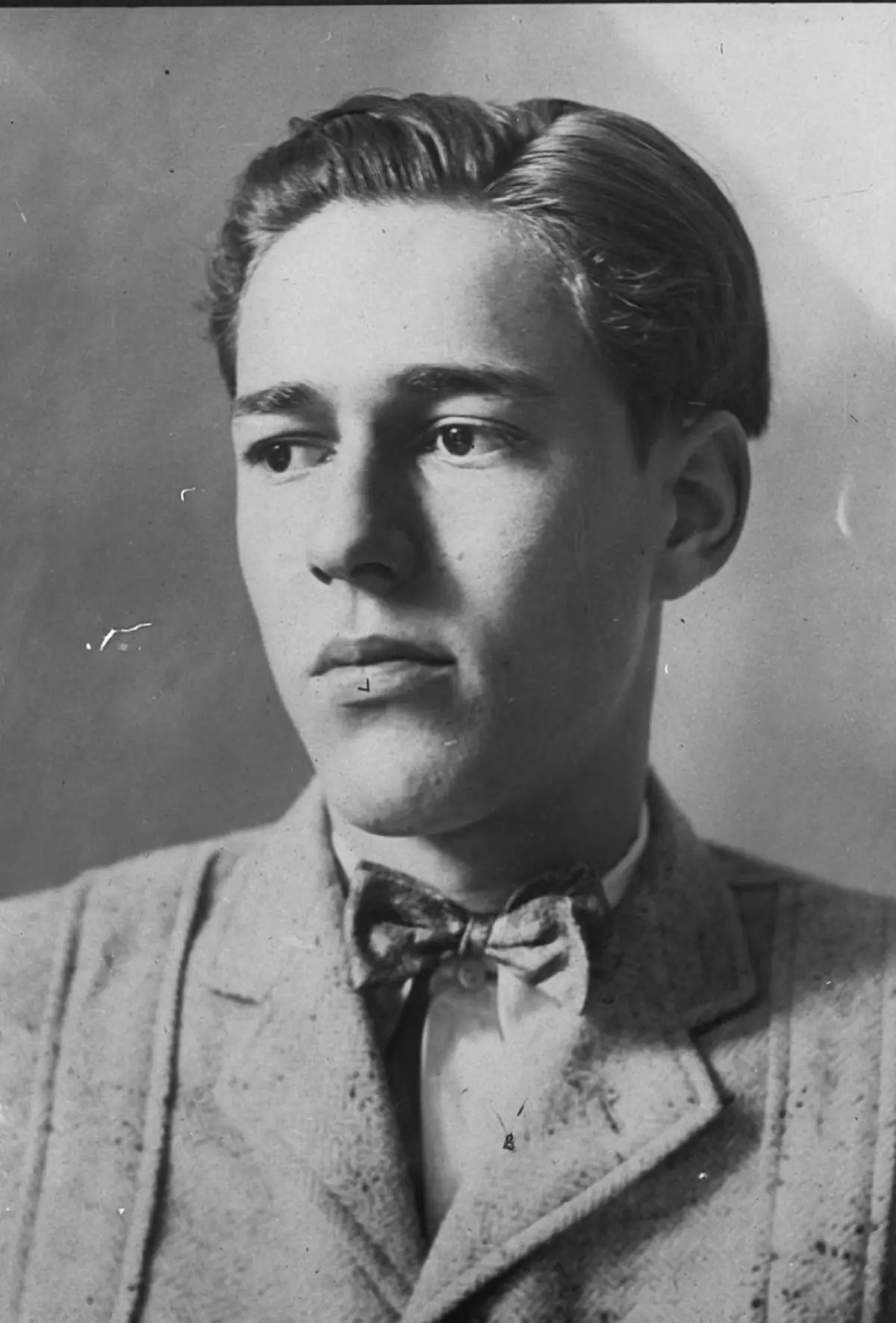

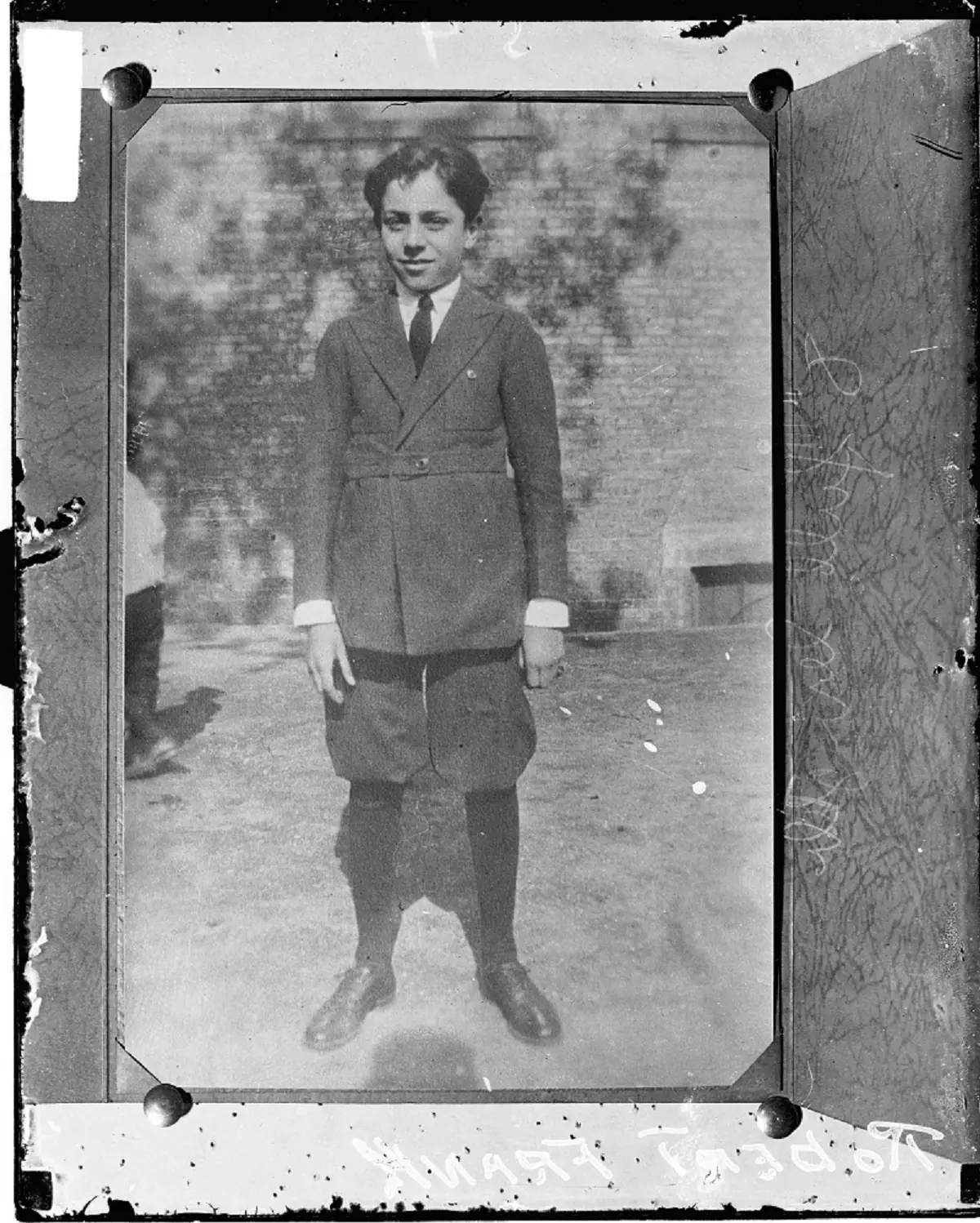

The accused, Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold, were very young—18 and 19 years old, respectively. Their victim was a child, 14-year-old Bobby Franks. Both came from wealthy families, had good names, and an ideal start in life. They confessed to the crime fairly quickly, the only difference in their testimonies being the identity of the actual murderer—Loeb accused Leopold, and Leopold accused Loeb. The prosecutor, Robert Crowe, demanded blood and sought the death penalty for the young criminals. The defense attorney, Clarence Darrow, became famous for his unprecedented closing speech, which lasted a staggering 12 hours and served as a grand address on life, humanity, and responsibility, directed at the American judicial system and society in general.

Such chaos in a courtroom would be unthinkable today, but at the time, it served its purpose—the boys avoided the gas chamber, instead receiving a sentence of life imprisonment plus an additional 99 years for kidnapping. The trial also dealt a severe blow to the credibility of psychiatry as a science at the time. Each expert witness, whether called by the defense or the prosecution, seemed to speak in an entirely different language, relying on completely different foundations. Even representatives on the same side could not reach a consensus. This glaring inconsistency on a fundamental issue significantly undermined public trust in the esteemed profession of psychiatry. Sigmund Freud himself was supposed to testify during the trial, but this ultimately did not happen due to the scientist’s extremely poor health.

Loeb was killed by another inmate, James Day, who slit his throat in the prison shower in 1936. Leopold, on the other hand, was released after serving 33 years in prison, in 1958. As might be expected, the story of these two unstable, amoral, yet in some ways fascinating individuals captured the imagination of filmmakers. Let us, then, examine the on-screen portrayals of Leopold and Loeb and consider how closely they reflect reality—or what purpose they might serve in doing so.

Rope (1948) – Brandon Shaw and Philip Morgan

Hitchcock’s film is a loose adaptation of Patrick Hamilton’s play of the same title, first staged in 1929. Chronologically, it is also the first cinematic reference to the Leopold and Loeb case.

Brandon (a stand-in for Richard) and Philip (a stand-in for Nathan) share an apartment and are preparing to host a party for a small group of acquaintances. However, the guests are unaware of the macabre centerpiece of the gathering. Brandon and Philip have strangled a former schoolmate, David, using the titular rope. David’s body lies hidden in a chest, covered with a tablecloth and topped with food and drink, as the guests gradually arrive—David’s father, his fiancée Juliet, a young journalist; Juliet’s former lover Kenneth Lawrence; David’s aunt Anita; and finally, the hosts’ former college professor, Rupert Cadell (played by James Stewart, who reportedly felt miscast and uncomfortable in the role). Meanwhile, the diligent housekeeper, Mrs. Wilson, moves about the scene, oblivious to the crime. Hitchcock references ideas that fascinated the real Nathan Leopold, who was deeply influenced by Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch (superman)—a being who is not bound by the moral constraints that govern intellectually weaker individuals. The second theme is the notion of murder as a form of pure art, something to be evaluated and analyzed intellectually, devoid of emotion, law, or morality. This perspective aligns closely with Richard Loeb’s almost entomological approach to crime.

In Rope, his on-screen counterpart, Brandon, is the voice and curator of the intellectual foundation for David’s murder, and he eagerly engages in debate—Rupert mistakenly believes it to be purely theoretical speculation. However, being unable to separate theory from practice, Brandon finds in Rupert’s arguments not only a confirmation of the legitimacy of his actions but also their logical justification. He lacks a moral compass—he is fully capable of distinguishing between good and evil, but the distinction does not interest him in the slightest. Hitchcock’s Brandon is a thoroughly corrupt social climber who constantly seeks an escape from boredom, a thrill, a challenge, or a chance to walk the razor’s edge. His ultimate goal is subversion, provocation, entertainment, and balancing on the brink. He is like a small boy pulling the wings off flies or pinning butterflies to a board. There is an element of true sadism in him—how else to explain persuading David’s father to feast in the vicinity of his son’s corpse and gifting him books tied with the rope that was used to kill him?

This is a sophisticated, narcissistic, and entirely immoral game that genuinely amuses Brandon, just as much as manipulating Juliet and Kenneth’s emotions does. He practically dares fate (in the person of Rupert) to prove the actual brilliance of his crime. Ah, this duality! On the one hand—perfection that ensures you won’t get caught, and on the other—the irresistible itch to show off your genius!

Philip, meanwhile, is depicted as a jittery, neurotic artist. What amuses Brandon is, for him, a source of stress and discomfort. He cannot control himself, drinks excessively, and constantly fears they will be exposed. Hitchcock’s counterpart to Leopold seems to be the victim of some undefined trauma, tormented by obsessive-compulsive tendencies and reluctant to respond to touch. In this particular vision, Philip is a simple coward. The real Leopold cited his attachment to Richard as the main motivation for his crime—we’ll return to this point elsewhere. In contrast, Philip goes along with the crime not to satisfy or keep Brandon, but because he sees no other way out. He is a man designed to follow commands like a compliant sheep and perpetually tormented by an energy-draining fear. Overall, there is more of Richard in Brandon than there is of Nathan in Philip.

Rupert Cadell’s final monologue, however, seems to be directly aimed at the foundations of Clarence Darrow’s famous plea. It can almost be regarded as a manifesto and protest. He speaks out for the equality of individuals and the respect for the right to life, while at the same time demanding the absolute eradication of those who claim an imagined superiority and prey on others. Rupert demands death for both murderers. He demands it in the name of the society threatened by their totalitarian theses, which are essentially a smokescreen for the celebration of private hedonism.

Murder by Numbers (2002) – Richard Haywood and Justin Pendleton

Richard (the counterpart to Loeb) is a high school charmer with undeniable charisma and a gift for persuasion. He is so charming and disarming that he effortlessly escapes punishment for both minor and major transgressions. He sleeps with girls, dominates parties, chain-smokes, and approaches life with utter nonchalance. Everything seems to go his way. In short, he’s a golden boy—bored to tears.

The psychiatric profile of Richard Loeb, prepared by one of the experts during the trial, highlighted his tendencies toward manipulation and pathological lying. According to the expert, Richard developed this defense mechanism in response to the strict discipline imposed on him by his governess. Forced from a young age into intellectual efforts far beyond his years, rapidly advancing through school at a much faster pace than his peers, he found himself caught in a serious dissonance between his mature, capable intellect and his emotional development, which remained at the level of a small child. To compensate for this disparity and alleviate his discomfort, he created an imaginary world and sought excitement in petty misdeeds, such as theft. A similar mechanism—though somewhat more psychologically complex—manifested in Nathan Leopold as well.

The on-screen Richard inherits from his real-life counterpart the mastery of deception and a penchant for manipulating others. Justin, on the other hand, is an outsider. Like Nathan Leopold, his intellect sets him apart from his peers, surrounding him with an air of strangeness. He possesses an excellent memory and is a master of detail, which makes him the brains behind the operation that culminates in the murder of a young woman and the framing of a high school janitor. Microtraces, physical evidence, victimology, profiling—he has it all down to a science (albeit theoretical, book-learned knowledge), which gives him a sense of power and control.

On the surface, these two characters seem to have little in common, but in reality, they are deeply dependent on one another, a fact they carefully hide from the world. While in the real-life events it was Nathan who idolized Richard, agreeing to every possible transgression in exchange for meticulously rationed sexual favors—and, according to his own words, even envying the drinks Richard consumed and the food he ate because “they became one with him”—in Murder by Numbers, the dynamic shifts slightly. In the film, it is Richard who is wildly jealous of Justin. He spies on him, follows him, and cannot forgive him for showing interest in a “mediocre” girl, Lisa. Richard does everything he can to sabotage the relationship, convincing Justin that he is the only person who truly appreciates him, that they need each other. One step further, and we’d have a full confession of feelings.

However, upon closer inspection, it becomes evident that Richard’s obsession stems more from a fear of losing control than genuine affection. His grand declarations serve as a leash he wraps around Justin’s neck.

Richard is acutely aware that—despite Justin’s dates with Lisa—Justin is fascinated by him, even physically. He exploits this, flirts, and constantly pushes the boundaries of their closeness. He knows full well that this unsettles Justin, throws him off balance, and yet increasingly ensnares him. Richard’s emotional manipulation and Justin’s intellectual analysis give rise to a toxic relationship, culminating in a murder that is, in theory, perfect. Unfortunately, the overly dramatized and unnecessarily prolonged Hollywood finale undermines this well-drawn dynamic, turning it into a boss-level showdown with a forced twist.

Compulsion (1959) – Artie Strauss and Judd Steiner

Compulsion – first a book, then a film – shook Nathan Leopold’s world to its core. As he admitted, reading it made him feel physically ill, as though he had been stripped naked and put on display under a spotlight for the amusement of a random crowd. This reaction stemmed from the fact that, while Leopold considered himself to be a completely different man than the one depicted in the film’s character Judd Steiner, they shared a mutual history—“a mutual history with a monster,” as he described it. Leopold decided to sue for defamation and invasion of privacy, but since those convicted of heinous murders cannot expect much sympathy from the judicial system, he naturally failed. Lacking a better option, he resolved to treat the whole ordeal as an unmedicated operation—painful but ultimately a part of his therapy.

All of this points to Compulsion being the most thorough and factually accurate portrayal of the Leopold and Loeb story, despite some fictionalized elements (such as the young reporter from Globe tying the threads together). The nature of the relationship between Judd and Artie is clear from the opening scenes. Artie is cracking up with laughter after stealing a typewriter from a fraternity house (later intended for typing up a fake ransom note). He’s amused, but not entirely satisfied. Meanwhile, Judd tiptoes around him, terrified by the mere thought that Artie might reject him, leave him, or act without him. No, Judd is willing to do absolutely anything to prevent that from happening. The smallest critical word directed at Artie provokes Judd’s aggressive defensiveness. For Judd, Artie has no flaws—he is exceptional, brilliant, a true gentleman, the very definition of perfection.

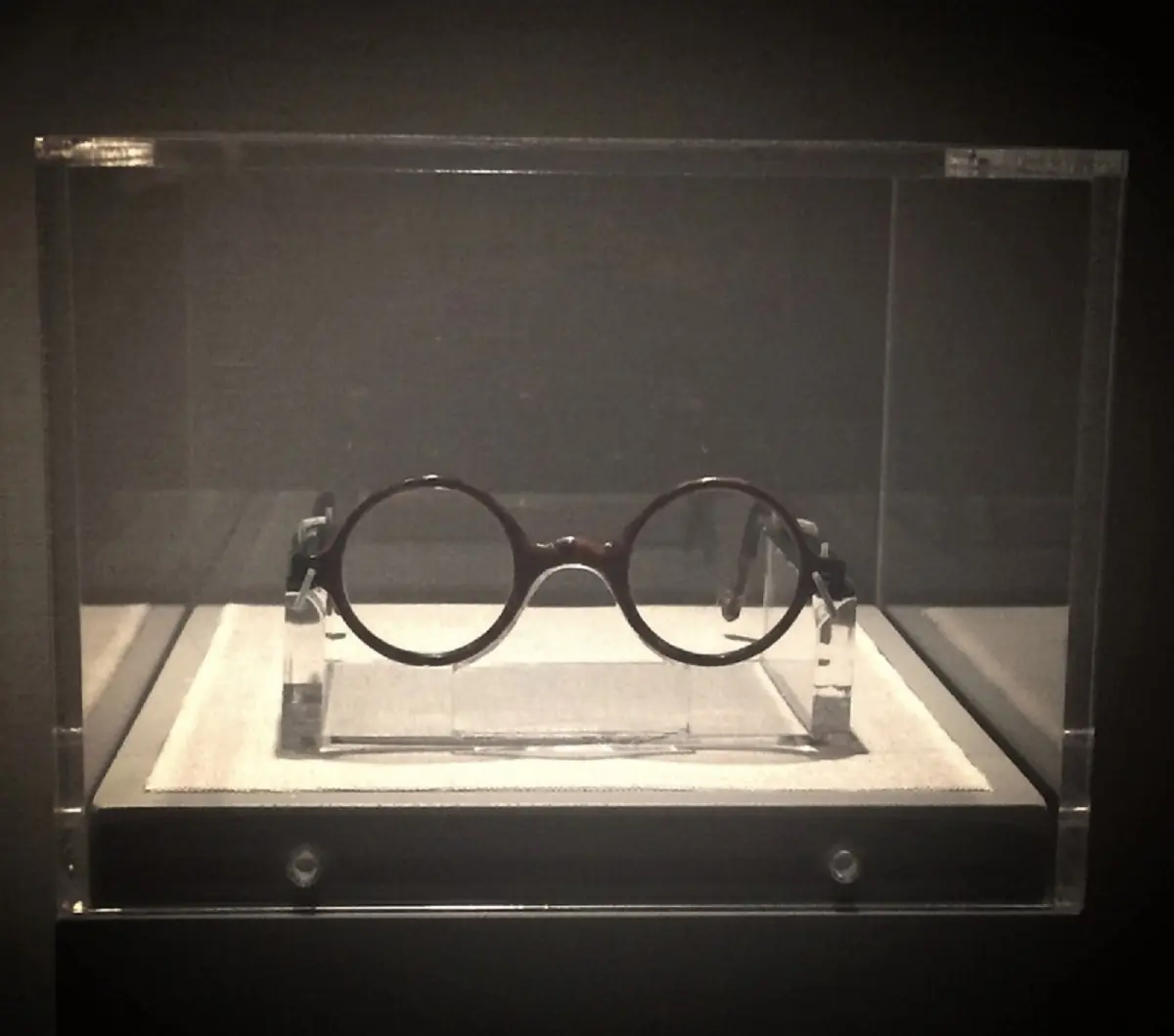

The boys are eager to try something “truly dangerous” and “truly exciting”—an experiment devoid of emotional coloring or genuine motive. As in real life, the victim’s family (in the film, Bobby Franks is renamed Paulie Kessler) receives a ransom demand, but before the money can be delivered, a passerby discovers Paulie’s body. The identification is unequivocal, though there’s an anomaly—the glasses. The boy didn’t wear glasses, and the ones found are too large for his face. The glasses found at the crime scene were, indeed, one of the most damning pieces of evidence in the Leopold and Loeb case. Unfortunately for Leopold, the glasses were part of a limited series, with only three pairs ever sold. Leopold unsuccessfully claimed that he must have lost them during one of his ornithological outings. This was the first glaring mistake in their supposedly “perfect” crime. The second was their choice of victim—a cousin, neighbor, and someone the boys had known for years. This was undeniable proof of their extreme arrogance and sense of invincibility.

Artie’s attitude toward Judd is rather dismissive. He’s the type who, like a child, quickly gets bored and—again childishly—is constantly seeking new sources of excitement. Just like the real Loeb, he is fascinated by crime and spins endless theories, casually suggesting potential suspects and charming women with his self-proclaimed status as the most informed man in the area.

Particularly compelling are the scenes where Judd struggles to reconcile his neat theories with the uncomfortable reality they’ve created. He is terrified as he realizes that his theories no longer hold up—they fail to emotionally desensitize him or enable him to act according to his will. His true desires remain unclear to him, which is why he so readily accepts “orders” from Artie. The idea of exploring various forms of vice and depravity (again, as an experiment) is credible but ultimately remains unrealized. “Murder is nothing,” Judd shouts at a girl he threatens with rape. However, when she responds not with fear but with compassion, Judd collapses under the weight of shame and helplessness. This is the moment he fails himself, his theories, and—most devastatingly—he fails Artie. As the tension mounts and their alibi begins to crumble, Judd loses his composure, while Artie basks in the spotlight like a salamander in fire, flashing his signature grin.

The second half of the film reconstructs the trial, the infamous “Trial of the Century,” featuring Orson Welles in a bold performance as Clarence Darrow (renamed Jonathan Wilk in the film). Clarence Darrow played a pivotal role in the lives of both boys, especially Nathan. It wasn’t just that his impassioned oration saved them from the death penalty. Darrow himself embodied an important lesson. Outwardly, he seemed lethargic, unkempt, a slow-moving writer—nothing like the higher intellect or übermensch Nathan had idolized. He was the type of person unnoticed at a party, someone who could disappear without anyone caring. And yet, Leopold—unlike Loeb, who had tenuous, insincere family connections and had lost his mother early—admitted that he had never known anyone with a heart as big, a kindness as deep, or a spirit as noble as Darrow’s. A staunch critic of cruelty and an opponent of any form of killing, even in the name of law, Darrow left a lasting impression on Nathan. Discussing Nietzsche with such a man would have been not only pointless but also foolish and childish. Nathan eventually understood this—but tragically, far too late.

The film also attempts to balance the courtroom drama by including perspectives from outsiders, particularly Ruth—a gentle young woman who manages to muster sympathy and compassion for the defendants. She even sees Judd as a “sick, wounded child.” Her perspective complements the defense attorney’s arguments, serving as evidence that his plea for understanding had some merit and justification.

Swoon (1992) – Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold Jr.

It is the only film in which Richard and Nathan appear under their own names and the only one that focuses entirely on their emotionally and erotically undefined relationship in reality. From a formal perspective, the film is a stylistic experiment—artistic, black-and-white cinematography, authentic period recordings woven in, and nostalgic music. This creates a certain intriguing, somewhat dreamlike atmosphere. However, in terms of content, the director ventures not just into uncertain, but even into dangerous waters.

In the film, we see Nathan and Richard as an openly declared couple, living together under one roof and socializing with others in their community. In reality, their relationship was far from that transparent. While Nathan was clearly in love with Richard and craved sexual contact with him (on special occasions, Richard would allow him, for example, to briefly insert his penis between his thighs), Loeb treated this arrangement much more instrumentally, using his friend’s fascination to exercise control over him and keep him at his service. A part of this dynamic might have also been driven by his constant boredom, which he tried to overcome through various experiments, including sexual ones. Thus, there was an erotic aspect to their relationship, but it certainly wasn’t one of established partnership and open play, rather it was a continuous tension and a game of cat and mouse.

However, the director goes even further. Having created the illusion of a faithful portrayal of the events – the kidnapping, murder, ransom demand, mutilation, and burial of the body, as well as the construction of an alibi – he subtly begins to drift into fiction. He does this in order to push through a preconceived thesis – namely, that Leopold and Loeb’s sexual orientation was their greatest guilt, that it condemned them to social ostracism and effectively deprived them of a fair trial. To achieve this goal, the filmmakers mix authentic statements from expert witnesses with fabricated additions, portraying Nathan and Richard almost as martyrs, distorted by the hostile social norms, who – unable to live openly in line with their sexual preferences – became lost in a world of imagination, ultimately losing touch with reality. This is not particularly fair, either to the murdered Bobby Franks or to the community, which surely deserves better representatives than Leopold and Loeb, regardless of what their actual relationship might have been.

After Richard Loeb’s death, Nathan fell into a deep depression. The loss of the love of his life was a blow from which he could never fully recover. Over time, however, he became a model prisoner. During his 33 years of incarceration, he mastered 12 foreign languages (and before prison, he could communicate in about 15 others), reorganized the prison’s library and educational system, and worked in the prison hospital. He voluntarily participated in experimental malaria studies, contracting the disease and testing treatment methods, risking his life, or at the very least his health. Guilt? As he wrote in his memoirs, it didn’t come immediately. It was a process that took nearly a decade. When it finally caught up with him, it would not leave.

The man who once preached the idea of the “superman” and demanded exceptional rights and freedom from social constraints left prison with one desire – to become someone completely anonymous, a tiny, gray cog in the machine. He worked as a technician at a hospital in Puerto Rico, graduated from the local university, where he later taught and conducted extensive research for the Department of Health, particularly on leprosy. He also returned to his old academic passion – ornithology – publishing Checklist of Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands in 1963. He married a widowed florist, although even in the late 1960s, he still openly admitted to his undying feelings for Richard Loeb. He died in 1971 from a heart attack caused by complications from diabetes.

Did Nathan Leopold’s exceptional intelligence – his IQ was around 200 – turn out to be a curse? How much truth is there in the claim that absolute brilliance in a particular field – something that applies to a fraction of the population – must be accompanied by serious deficiencies in other areas: health, relationships, the ability to maintain healthy social connections, or morality? Although intellectually the idea of the “perfect crime” excited Leopold, much like the theoretical musings of Nietzschean philosophy, it’s likely that, in other circumstances, the need to test his reflections in practice would not have arisen. Leopold was largely a theorist, a debater, and a scholar. His dependency on Richard Loeb influenced the rest.

In his fantasies, he was a servant to a king (but also a king among servants), carrying out royal orders in exchange for granted favors. The subsequent crimes – thefts, break-ins, arson, and finally murder – were simply a means to an end, perhaps uncomfortable but necessary elements of the equation that had to be considered. To this day, it is still not entirely clear which of them – Leopold or Loeb – actually killed Bobby. In the context of their relationship, it’s not even that significant – both are fully responsible for what happened. Loeb, because he believed everything was his right and that he was entitled to everything. Leopold, because he believed Loeb had the right to everything and was entitled to it all.

Karolina Chymkowska

In books and in movies, I love the same aspects: twists, surprises, unconventional outcomes. It's an ongoing and hopefully everlasting adventure. When I don't write, watch or read, I spend my days as a veterinary technician developing my own farm and animal shelter.