GONE WITH THE WIND Explained: A Controversial Icon

…—some spicy, others intriguing, and still others in their own way melancholic. The journey to creating Gone with the Wind was long and tumultuous, but it ultimately resulted in a film that is more than a masterpiece of cinematic art—it is a true monument to the Golden Age of Hollywood and the rules that governed it unchallenged.

The astounding popularity of Gone with the Wind published in 1936, which earned its author, Margaret Mitchell, a Pulitzer Prize, practically guaranteed its adaptation to the big screen. The power of the book—and later the film—proved so overwhelming that it successfully convinced thousands of readers worldwide of the authenticity of its portrayal of the Old South. It also cemented in their consciousness the myth of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, much to the dismay of scholars and experts of the era.

The driving force and ultimate decision-maker throughout the filming process was the producer, David O. Selznick. In essence, this is primarily his film—regardless of who ultimately took the director’s chair. George Cukor, quickly dismissed from the role, was replaced by Victor Fleming, who, due to exhaustion, briefly gave way to Sam Wood. In the end, it was Fleming whose name appeared on the posters as the director, but the puppet-like nature of this role in the case of Gone with the Wind was widely known even before the film’s official premiere.

As for Selznick, he had one primary dream—to cast Clark Gable as Rhett Butler. This turned out to be an arduous endeavor, consuming two years of effort. These were times when ironclad contracts with powerful studios bound actors indefinitely, stripping them of any freedom in choosing roles. Gable was under contract with MGM, a studio notorious for not lending out its stars. Negotiations dragged on for months, with ever-increasing sums being offered. In the end, Selznick succeeded, but at a steep cost. To think that at the very beginning of this journey, he wasn’t even interested in the project!

The grueling battle with MGM was, of course, just one piece of the puzzle. Another was the work on the screenplay. The initial version, drafted by Sidney Howard, was so lengthy it would have required six hours of screen time. Ben Hecht was hastily brought in and given a mere five days to rework it. He managed to complete half, after which David O. Selznick himself took over as screenwriter. However, due to his struggles with meeting the deadline, the job was ultimately finished by the original author, Sidney Howard. Howard is credited as the screenwriter not only because the final version closely aligned with his vision but also as a tribute—he tragically died in an accident before the film’s release, at just 48 years old. Posthumously, he was awarded an Oscar for Gone with the Wind.

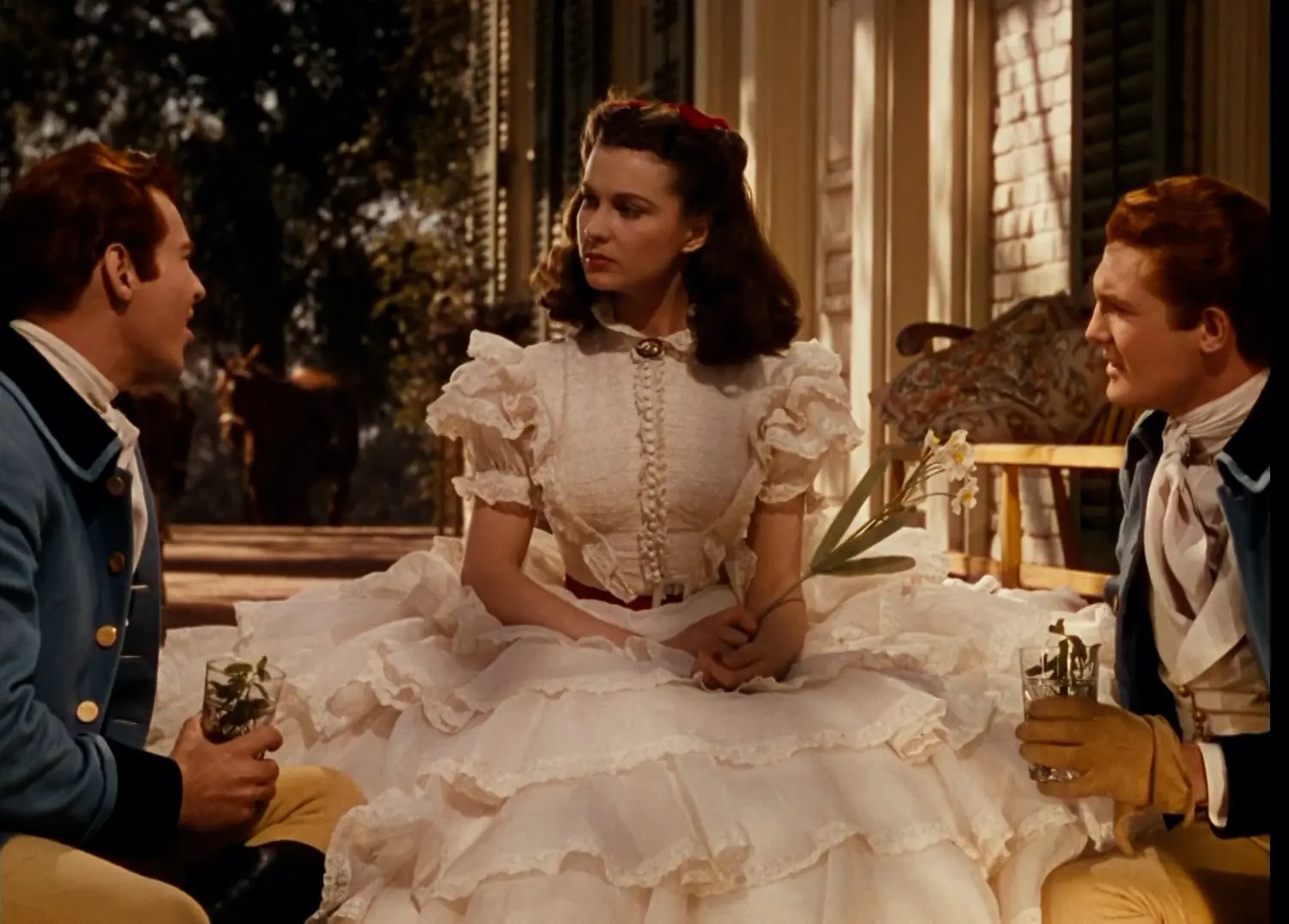

The most challenging task, however, turned out to be finding the right actress to play the lead role of Scarlett O’Hara. Selznick began his search among unknown talents, announcing a casting call that attracted 1,400 applicants. This move was primarily a marketing strategy, as it was clear from the outset that the role of Scarlett would not go to an unknown actress.

Two stars energetically campaigned for the role—Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn, the latter convinced that the role had been written specifically for her. Selznick did not share this conviction, which he expressed in rather blunt terms. MGM’s leading actresses, Joan Crawford and Norma Shearer, were also considered, though Shearer ultimately withdrew from the competition. The list of hopefuls included Lana Turner, Jean Arthur, Tallulah Bankhead, Joan Bennett, and Miriam Hopkins, who, according to rumors, was Margaret Mitchell’s favorite. Officially, however, the author did not endorse any candidate.

By late December 1938, only two contenders remained: Vivien Leigh and Paulette Goddard. Initially considered “too British” for the role of Scarlett, Vivien Leigh quickly emerged as the dark horse, partly due to her French-Irish heritage, which mirrored that of the literary character. Paulette Goddard, on the other hand, was ultimately disqualified due to her scandalous romance and marriage to Charlie Chaplin.