Dissecting MAKING A MURDERER: Fascinating and Shocking

Manitowoc, a small county in Wisconsin. In the Chippewa Indian language, its name means “the place of the great spirit.” Located on the shores of Lake Michigan, it houses its administrative center and main city, also named Manitowoc. In the 1960s, a 9-kilogram fragment of the Soviet Sputnik 4 fell on North Street. It was quite an event. Around the local factory, the climate is humid, with extreme temperatures in both summer and winter. Tourists, if they visit, usually come for the maritime museum. About 8% of the population lives in extreme poverty. Overall, it’s a rather dull place to live. But relatively safe.

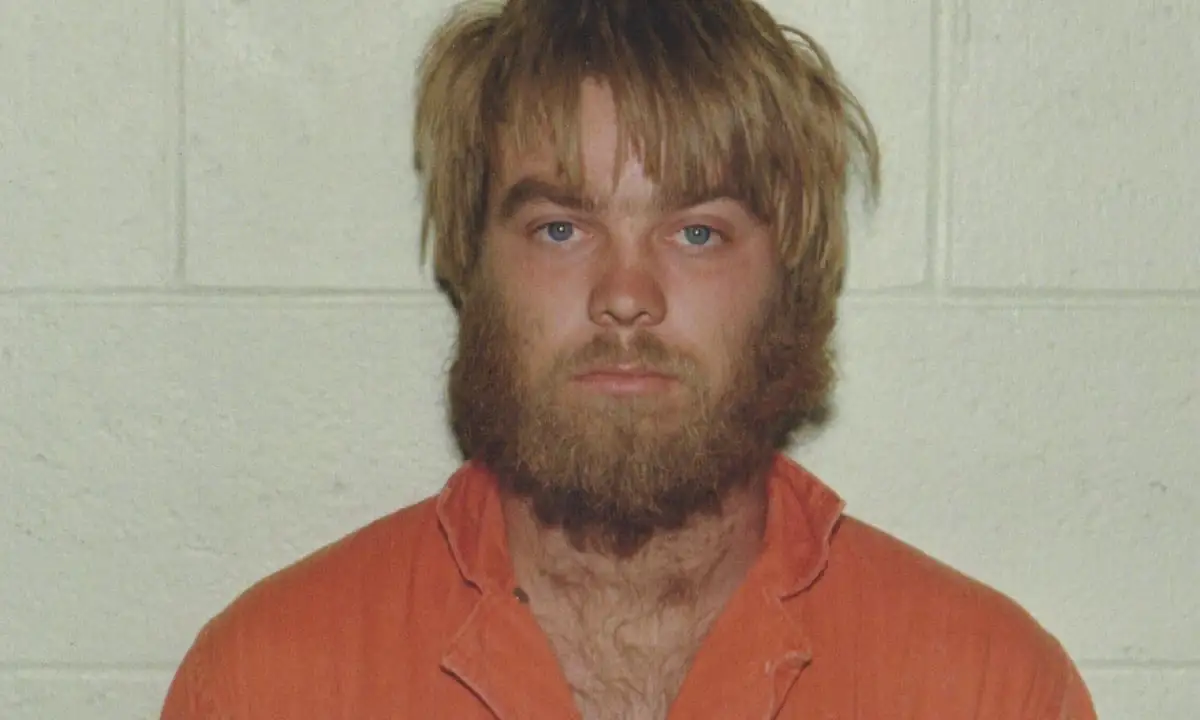

It was in this city, in July 1962, that Steven Avery was born. His family had lived there for generations and had always run a junkyard. The street itself was even named after them. The Averys were somewhat looked down upon by others and kept to themselves, equally aloof and detached from their surroundings. Dolores, Allan, and their children—Earl, Chuck, Barb, and Steven—later extended into a larger family unit. A unique micro-community, like a town within a town, or a state within a state. Making a Murderer.

At school, Steven performed averagely. His IQ was around 70, as the psychologist stated. But his mother says he was always truthful. Since he was a child. When he did something wrong, he admitted it. Childhood mischief turned into more serious offenses. Burglary, then cruelty to animals. Two convictions. I was young, stupid, and hung out with the wrong people, he said. Then his cousin accused him of exposing himself to her and jumping in front of her car, waving a gun. He explained that he wanted to put an end to the rumors she was spreading, claiming the gun wasn’t loaded. That he was a family man, a father of four, a devoted husband to Lori. However, as a repeat offender, he faced six years in prison. And it might have ended there, had it not been for the tragedy of Penny Beerntsen.

Penny’s family was everything the Avery family was not. A pillar of the community, a member of the church. She herself was charitable, socially active. In July 1985, she was jogging on the beach, as she often did. A man appeared out of nowhere. She didn’t stand a chance. He dragged her behind the tree line, brutally raped and beat her. Shaken and deeply traumatized, the woman was found by passersby, who immediately called the police.

Where was Steven Avery at that time? According to the testimony of sixteen witnesses, corroborated by receipts from the cash register, he was shopping with his family more than 60 kilometers away in Green Bay. However, the alibi seemed to mean nothing. The fact that his accusing cousin was married to a law enforcement officer also worked against him. His public defender, an average attorney, couldn’t do much. Of course, samples were taken and cataloged—but who in 1985 had heard of DNA testing? Penny described the appearance of her attacker, and a sketch artist created a drawing. Of course, he later denied that the composite was based on a photo of Steven Avery. However, the sketch resembled him exactly, and it’s hard to blame Penny for identifying Steven when confronted with a lineup of suspects.

The community was outraged. Many were convinced that Avery was innocent. His family stood by him, especially his mother. But it didn’t help—he was found guilty and sentenced to thirty-two long years in prison. He spent eighteen years behind bars until activists from the local branch of the Innocence Project conducted DNA tests. Avery was innocent. The real perpetrator turned out to be a man named Gregory Allen, a convicted rapist. While Avery was in prison, more women suffered at Allen’s hands. This could have been avoided. Allen’s records were with the county police. But for some reason, they were ignored, as was a later phone call after Allen was arrested for another crime. A neighboring county suggested they had “the wrong man.” However, no one found it necessary to file a report or even make a note.

Avery was released in October 2003. His wife had left him, taking the children, many years earlier—angry and threatening letters he had sent her were still preserved. However, he found new love, and his family embraced him warmly. His case garnered nationwide attention, including the introduction of a new law aimed at reducing the possibility of wrongful convictions. Encouraged by this atmosphere, Avery’s lawyers urged him to file a lawsuit for compensation, targeting the very top—the former sheriff, Thomas Kocourk, and the former prosecutor, Denis Vogel. Essentially, the police and the prosecutor’s office as a whole, from low-level clerks to investigating officers. The scale of the compensation was also substantial, as Avery initially demanded thirty-six million dollars.

Teresa Halbach was a successful freelance photographer. She ran her own website, had plenty of assignments, and loved her work. Sometimes, she took artistic photos; other times, she had regular gigs that helped her pay the bills. Then she would get behind the wheel of her Toyota Rav4 and head to an appointment. In October 2005, she was scheduled to meet with Avery to photograph a car his sister was selling. According to Avery, she arrived, took the pictures, exchanged a few words about nothing in particular, and then left. The problem was that no one ever saw her again. Teresa Halbach disappeared. Without a trace.

Of course, the police immediately focused their attention on Avery, and with great intensity. This was especially true when two emotional members of a search group found a discarded Toyota, carelessly covered with branches, at the edge of the scrapyard. Then, days of searches ensued, and finally—on the sixth attempt—a car key was found, slipped under a slipper in Steven’s bedroom. And then there was the bloodstain next to the steering wheel—it was his. And finally, fragments of burnt bones in the backyard. The public was outraged. Had a cold-blooded murderer been released two years earlier? If Steven Avery had remained in prison, would the young, innocent woman still be safe at home with her loved ones? The Innocence Project stopped showcasing Avery’s photo on their website. Avery, on the other hand, adamantly maintained that he was being framed and that the evidence had been planted. On his side were two attorneys, Dean Strang and Jerome Buting. Thus began the long, exhausting, and frustrating legal battle.

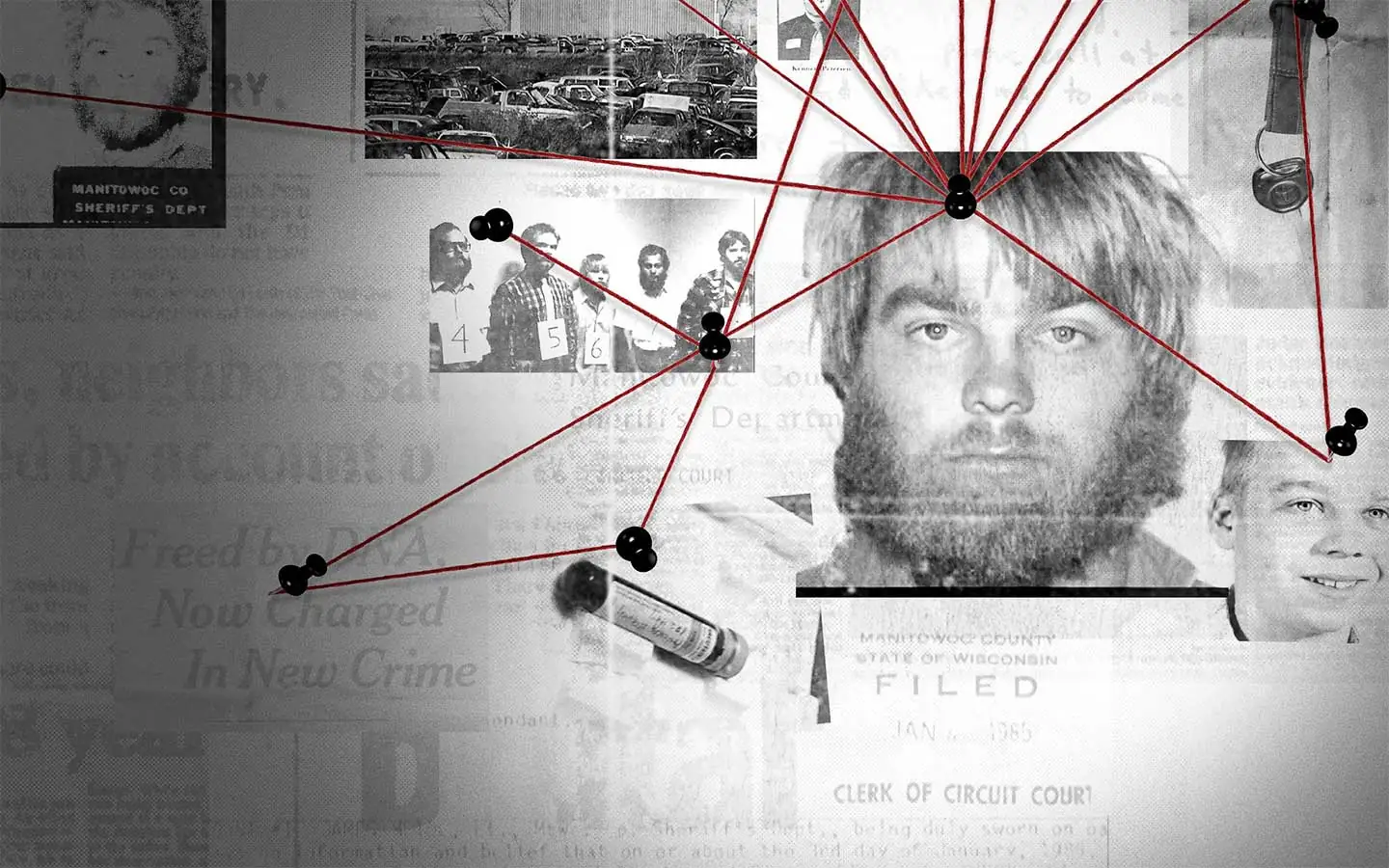

The Making a Murderer series was produced over a span of ten years. Its creators, Laura Ricciardi (a lawyer by training) and Moira Demos, compiled hours of interrogation recordings, documents, reports, interviews, television statements, and video footage from the trial. They spoke with families, neighbors, community members, observers, police, lawyers, and prosecutors. They used phone conversations made by Avery from prison. In short, they did a monumental amount of work and gathered tons of material, which was then edited into a ten-episode documentary series, as thrilling as the best crime thriller. It has been rightly compared to the famous The Jinx and the serial podcast Serial focusing on the brutal murder case of Hae Min Lee.

Of course, it also sparked significant controversy. The main criticisms were about its one-sidedness and emotional manipulation. Teresa Halbach’s family was outraged and deeply hurt, claiming that their loss had been deceitfully used to create an unfair media sensation, which solely presented the Avery family’s point of view. Prosecutor Ken Kratz, who acted as the prosecutor in Steven’s trial, accused the filmmakers of omitting mention of several key pieces of evidence against Avery. Moreover, he claimed they had refused an interview he had requested. Ricciardi and Demos, however, argued that it was the other way around—that Kratz refused to speak and did not respond to their calls. A somewhat surprising voice in the film came from Steven’s former fiancée, Jodi Stachowiak, who was portrayed as a champion of his innocence, gradually broken down by her own probation officer’s harassment. Today, she claims that, in her opinion, Avery is guilty, as he also “resorted to threats” against her and her family, saying, He better think twice before speaking on camera, or else he will regret it and. All the bitches owe me something in the name of the one who sent me to prison. In the background, there also appears to be an alleged statement from a fellow inmate of Steven’s, to whom he supposedly confided his desire to build a torture chamber where he could rape, torment, and kill women.

It is quite natural that the personally involved parties, when discussing Making a Murderer, refer to the question of Steven Avery’s guilt or innocence. After all, that is at the core of their interest. However, the true role of this documentary is not to settle that question. Proving guilt is the prosecutor’s job, rendering a verdict is the court’s responsibility, and presenting justified doubts is the role of the defense. Each of us, as viewers, is entitled to form our own opinion, but we are not in a position to definitively judge guilt or innocence.

Making a Murderer primarily deals with the complex and difficult issue of the presumption of innocence and the effectiveness of procedures when compared to the limits of human error and the challenges posed by human weakness. In theory, everything looks simple and textbook-like: crime, evidence, analysis, witnesses, theories, defendant, interrogations, trial, presentation of material, verdict, punishment. Simple as a hammer. But of course, it is by no means so straightforward. Our deeply human need for safety and functioning within certain established frameworks extends to legal structures and order, and thus to those who represent them. We want to believe that they have effective means at their disposal. That they use them as intended. That they act objectively. That truth and innocence will always prevail as the final argument.

Meanwhile, we watch in disbelief as two detectives cold-bloodedly manipulate the testimony of an obviously intellectually impaired young man, Brendan Dassey, who, to the best of his limited intellectual abilities, tries to guess what they want from him. Are the detectives acting with malice? Not necessarily. They are convinced of the guilt of the suspect and co-defendant and want justice in the name of the murdered woman. Their frustration and desire to secure clear evidence are completely understandable. However, the way they pursue this raises serious concerns. Can we truly trust that innocence and staying out of trouble guarantee that we will never find ourselves in this boy’s shoes? Can we trust that facts alone provide a sufficiently strong shield of defense?

Where we would expect objectivity, an impartial presentation of facts, we instead find strange personal and familial connections, the tight-knit influence of a closed community, and once again the question arises: what will prove stronger? Blood ties or professional responsibility? Responsibility for one’s own domain or the fear of, say, a corrupt superior? We expect a thorough analysis from a responsible expert, but instead, we get the nervous testimony of a lab technician who contaminated a unique piece of evidence because she was giving a lecture over it to two students. And then there’s the man who spent eighteen years behind bars for a crime he did not commit. How might those years have affected him? What did they do to his character? How did they influence his morality and respect for the law? Did they awaken his darker instincts? Could they have turned a petty thief into a murderer? It’s not about whether this actually happened. It’s about whether it could have happened. In this case, or any other.

These chilling reflections make up the first layer of Making a Murderer, and the first element that makes this documentary such a fascinating experience. The second is the courtroom record itself, which resembles a duel between fencers, alternately landing and parrying blows. Small gestures. Carefully considered statements. Clever psychological moves, pauses in questioning, voice intonation, raised eyebrows. And overwhelming piles of evidence, with conversations between the two defense lawyers that go beyond the specifics of this trial, touching on the philosophy of practicing law, its letter and spirit, where the paragraph ends, and the drama of the individual begins (and vice versa). Over all of this hangs the inescapable fate, the dark sense that the battle, however skillfully fought, is already lost. The courtroom episodes carry the atmosphere of a Shakespearean tragedy, the authenticity of a report, and the weight of a psychological chess game at its peak.

And finally, the third layer, the saddest one: the tragedy and the circles it creates, much like the ripples on water when a stone is thrown. There is the victim and her loved ones, demanding justice, yet their lives will never be the same again. There is the mother of the accused, growing older and more frail with each passing year, his sister torn by doubts, his fiancée ostracized, children living with the stigma of having a father labeled a murderer. There is the police officer, whose procedural errors are exposed and who is accused of dishonesty, and his family, who will also face the consequences of being in the spotlight. Even the filmmakers themselves become part of this intricate web of interconnections and interdependencies. The tragedy doesn’t end with the crime itself; it extends far, far beyond it.

All three of these layers contribute to a fascinating, though mentally exhausting and largely sad, cinematic experience. It’s better to break the viewing into several sessions—first, because it’s difficult to process everything in one go as the feelings are too overwhelming, and second, to give oneself a chance to reflect. And many reflections arise in relation to Making a Murderer. Most of them are far from optimistic.

Steven Avery is currently serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole at the Waupon prison. Brendan Dassey, also sentenced to life, will not be eligible for parole before 2048. In December 2015, a petition demanding the exoneration of Avery and Dassey was sent to the White House, signed by over half a million people. In response, a spokesperson for Barack Obama explained that the president cannot make such a decision in a state-level case. The spokesperson for Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, who has the authority to make such a ruling, stated that Walker does not consider such a decision. In January 2016, Chicago lawyer Kathleen Zellner, in cooperation with the Innocence Project, filed another appeal in Avery’s case. That same month, People Magazine published an article revealing that one of the jurors in the original trial was the father of the Manitowoc County deputy sheriff, and the wife of another worked as an official in the local town hall.

Buting and Strang continue to practice law successfully. They are reluctant to speak about the Avery case. Prosecutor Ken Kratz resigned after several women accused him of sexual harassment. After a temporary suspension of his license, he returned to his legal career. In a lengthy letter, Steven Avery addressed the public directly: The real murderer is still at large and is probably lying in wait for another victim. Upon learning of statements from his former fiancée, Jodi Stachowiak, he bitterly commented: I wonder how much they paid her.