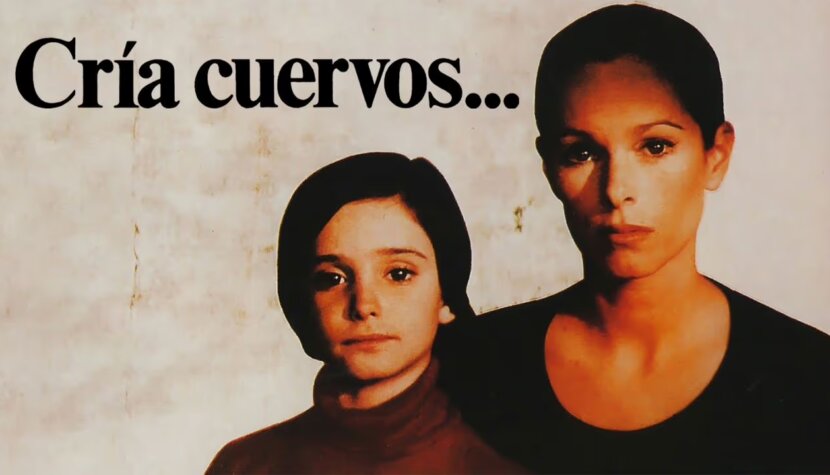

CRÍA CUERVOS / RAISE RAVENS Explained: The End of Innocence

Todas la promesas de mi amor

Serian contigo,

Meolvidaras, meolvidaras.

Junto a la estacion hoy llorare

Igual que un nino,

Porque te vas, porque te vas,

Porque te vas, porque te vas…

Carlos Saura’s film, Cría Cuervos / Raise Ravens was often described as a journey into the land of childhood. To some extent, it indeed is. However, not entirely. We observe a slice of young Ana’s life—we do not know her age; moreover, the film’s temporal plane remains undefined, as if the director wanted to depict a mythical land, a spatial equivalent of the everyman, something that could happen at any time and always remain true. Ana is an orphan; her mother likely succumbed to cancer, and her father died shortly thereafter. Ana and her sisters are placed under the care of their mother’s sister, Aunt Paulina, and a trusted servant, Rosa.

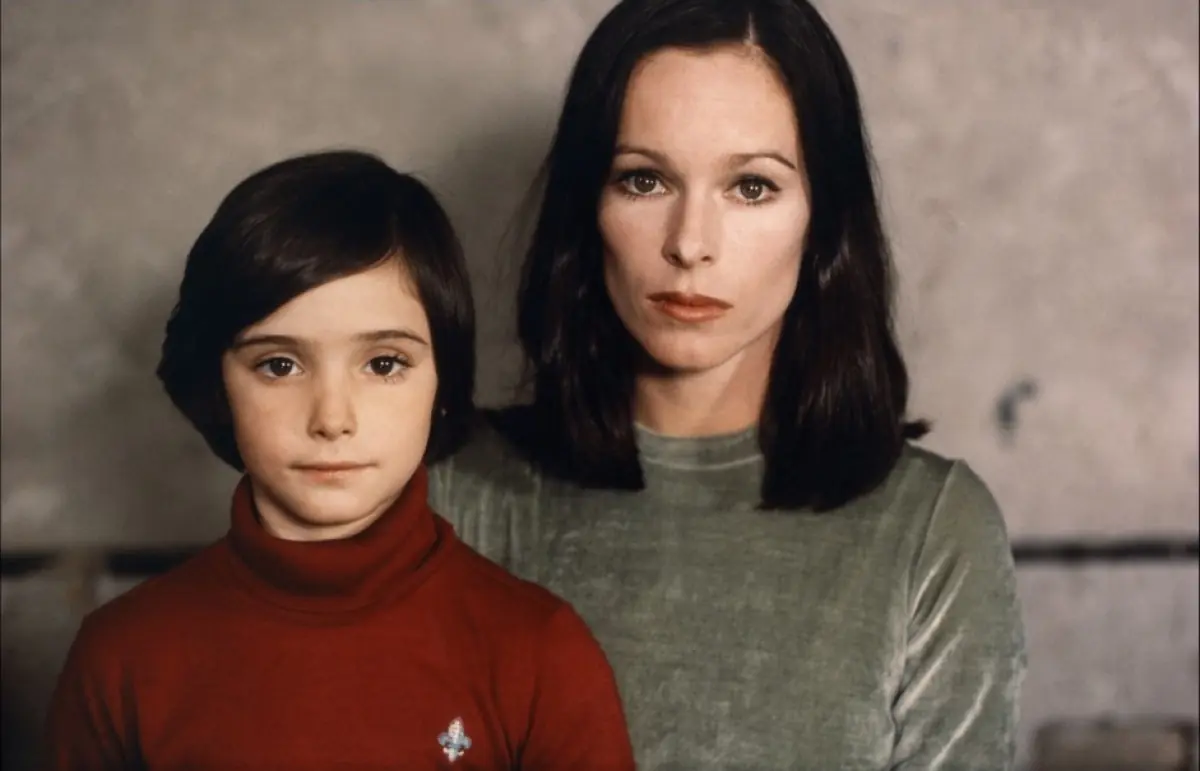

The story, likely unfolding during one summer vacation, is narrated from the perspective of the now-adult Ana—brilliantly portrayed by Geraldine Chaplin, who also played the girl’s mother. Ana is precociously mature for her age, perhaps because she has seen so much. This difference, this tendency to escape into the world of imagination, separates the girl from her sisters. This is evident, for example, in the scene where we see the solemn, pensive protagonist in the foreground while her carefree sisters play in the background. This land of imagination is built from a mixture of memories, imaginings, and desires.

Ana’s most treasured memory is of her mother. To the girl, her mother was the ideal embodiment of love and kindness. Thus, Ana subconsciously blames her father for her mother’s illness and breakdown: she witnessed their arguments and later saw her mother writhing in pain during the final stages of her illness, repeatedly expressing a desire for death, declaring that heaven does not exist—that heaven is empty. This statement about longing for death becomes a kind of incantation: Ana recites it when the world feels unkind and alien, as if the concept of death merges in her imagination with the image of her mother. A small incident from when her mother was still alive and healthy gave the girl a sense of power, a conviction that she is like fate—able to decide life and death.

It happened when her mother handed Ana a jar she found during cleaning and told her to throw it away. Ana naively asked if it contained poison, and her amused mother confirmed it. Yet for many months thereafter, Ana cultivated the belief that she truly possessed a lethal weapon. She likely sees herself as the cause of her father’s death, whom she subconsciously blamed for her mother’s suffering and illness, imagining she was avenging everything he had done—especially his extramarital affairs and the disdain and lack of understanding he showed his wife. Ana is too young to comprehend the intricate complexities of her parents’ marriage, but her intuition tells her that the person she idolizes is being wronged.

The viewer, however, can see it differently. Ana’s mother is a hysteric, mentally unstable, manipulating her husband with her illness even when she is still perfectly healthy, demanding spasmodically signs of affection and attention.

At a certain point, we fall into the same trap as Ana, equally defenseless, succumbing to the illusion that the words about desiring death hold magical power. “This woman summoned death through sheer force of will,” we think, astonished. It happened as she wanted—she truly fell ill. The sudden blow that struck Ana’s mother out of nowhere, after a long period of hysteria and hypochondria, is in a way her triumph. She finally managed to show how profound, real, and acute her suffering is. It’s as if she finally could repay, in the harshest way, the people who diverted her from her true calling, from being a pianist. The illusion grows to the point where we are ready to condemn this woman for her cruelty and selfishness. Only later comes the reckoning.

We regret these unwise thoughts, seeing the three orphaned children, the deceased’s sister, trying her best to fill the void left in her own and the children’s lives, but encountering only aggression and rejection. In truth, the cry for death is a plea for continued life, a desperate request to be freed from pain, a cry of terror. Little Ana helps us understand this truth, echoing the reality in the same way.

When Ana offers her ill, paralyzed grandmother assistance in crossing into eternity, we witness an astonishing yet silently expressed affirmation of life. The grandmother feels lonely; all she has left are memories of her youth and social life. However, these memories are slipping away, becoming fewer and fewer. When the elderly lady becomes aware of this loss, she has a moment of despair. But it is brief—she has learned to value equally what comes and goes. She clings to life as long as she can still experience happiness, even fleetingly, and remains grateful for all the moments she has lived.

These unpredictable combinations of tragedy and hope, life and death, passion and reason serve as a potent stimulant for the awakening femininity and unconscious eroticism of the girls. The longings that grip them are still vague, the desires they experience—unintelligible.

However, like all girls their age, they feel almost grown-up, and although they still prioritize play, it takes on a peculiar form. They stage a scene where they play adult roles, uttering lines they must have heard in the family. The seriousness with which they engage in this play is deeply sad—it touches not on thoughtless mimicry but on the adoption of patterns. It is another proof of how easily we forget that adults’ actions rarely escape children’s notice, even when they are presumed to understand nothing.

Ana, now an adult, observes that childhood is often called a time of happiness and carefreeness, but she remembers hers very differently. And indeed—the mythical innocence of childhood can be relegated to fairy tales. For a time, Ana was able to feel better and stronger than those around her. Perhaps this belief had a therapeutic effect on her? Undoubtedly, she managed to tame her longing, as she never truly allowed her mother to leave entirely. In her imagination, her mother was always near—able to lull her to sleep, tell a story, play the piano. Everything remained exactly as it was; nothing had changed, not even the refrigerator’s contents. One could live in the illusion that life unfolds as one wishes.

And just when it seems almost certain that such magic will work—Ana clearly sees her mother walking down the hallway, truly not gone, perhaps just away on a concert trip?—the singular moment arrives when one must abruptly and truly grow up. The story of Thumbelina remains the same—but now someone else is telling it. And so it will always be. Ana reacts to this necessity with aggression and hatred, attempting to resist, waging war against fate by reaching for what she believed to be her infallible weapon—poison. She still thinks that wishing her aunt death will summon it. But death does not listen and never has.

Disappointment and disillusionment soon give way to fear and confusion, the apprehension familiar to us all: that we cannot fully protect our loved ones, that there is something wielding unchecked power over us, even when it appears submissive and benign. One day, the prayer to the Guardian Angel will not revive her sisters, just as it “revived” them during a game of hide-and-seek. One day, there will inevitably be a boundary that cannot be crossed, no matter how much one desires it. Ana must reconcile herself to the order of things, to destiny’s decrees, and accept her fate as it is.

The symbolic expression of this submission is the return to school, where summer freedom is replaced by duties and a strictly regimented daily schedule. The borrowed shoes, which added height and allowed her to tower over the world, are replaced by a school uniform—just like everyone else’s. The song that allowed her to feel special, to dance, and to wear an imaginary elegant hat becomes just a memory, an ephemeral melody increasingly disconnected from real life. Hence, feeding the crows always ends painfully for the feeder—there are forces that cannot be tamed or subdued.

The film—also known by the titles Cría!, Raise Ravens, and The Secret of Anna—won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1976.