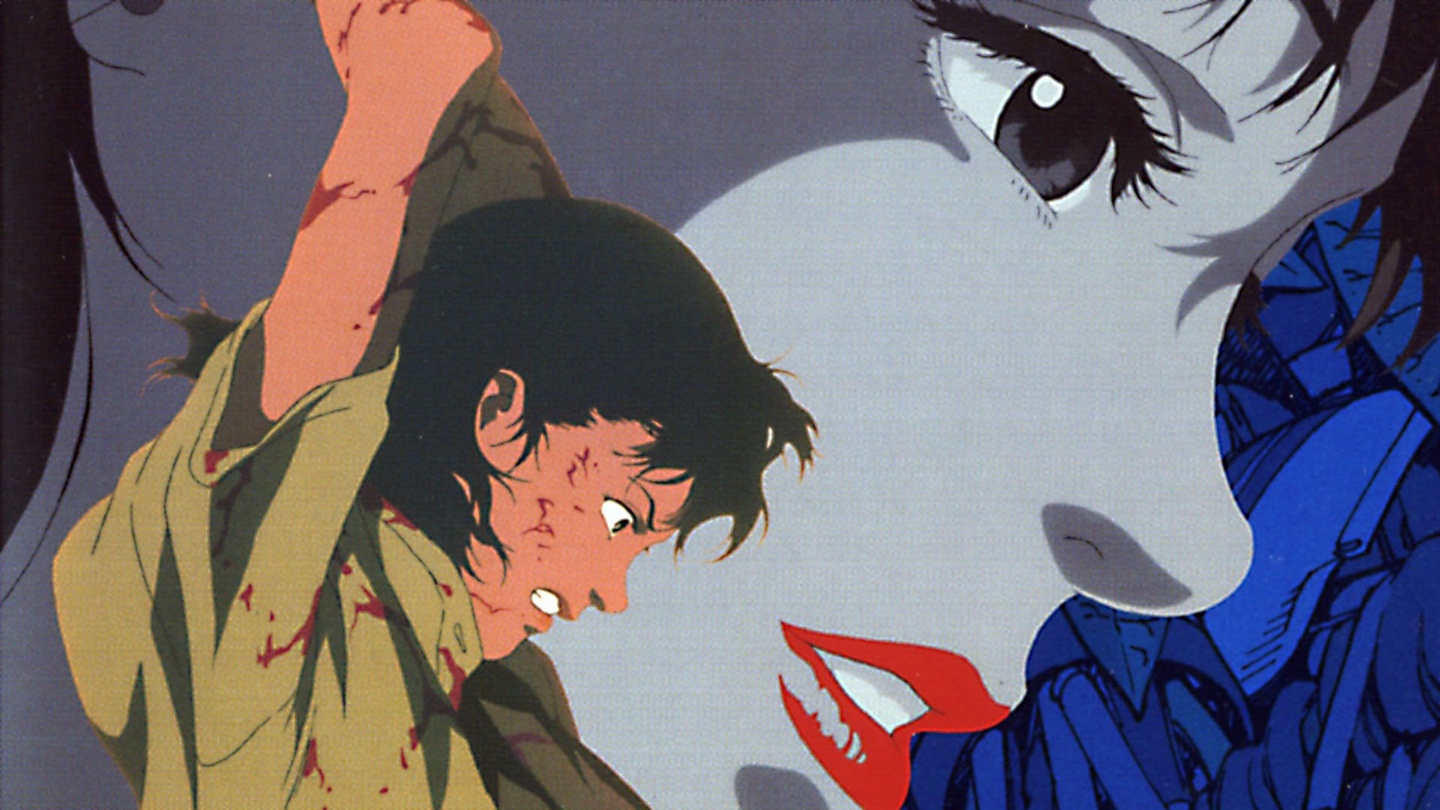

BLACK SWAN vs. PERFECT BLUE: Homage, Plagiarism, Adaptation?

However, the film resonated not only with fans of his talent and psychological thrillers but also with aficionados of Japanese cinema. While the former were mostly captivated by the emotional landscape the New York director crafted, the latter quickly accused him of plagiarism, noting many similarities to the cult anime Perfect Blue. Despite these undeniable parallels, Aronofsky has long denied these allegations, citing entirely different inspirations and goals. But what if both sides are somewhat right?

Darren Aronofsky likes to stir controversy. Despite his extraordinary talent that allows the Brooklyn-born director to create spectacular films even on subjects deemed dull and uncinematic by others, his career still seems to balance between being part of the Hollywood elite and a desire to create art films, leaning more towards the latter. Although he tackles completely different themes each time, most of his films carry certain trademarks – they are filled with sorrow, dreamlike visions, and brutally honest messages that are often unacceptable to audiences expecting happy endings but delight fans of dark genres – from painful dramas to psychological thrillers. Aronofsky wouldn’t be Aronofsky without one more ingredient – many allusions to other works of cinema, literature, and art. Black Swan, Perfect Blue.

(Obvious spoiler alert)

The issue of similarities between Perfect Blue and Black Swan is nothing new, but discussions on this topic remain lively even after many years. I also have a problem with this because I sincerely love both films, but I am far from accusing a man I consider one of my favorite directors of plagiarism. It’s not sympathy that drives me but rather the facts that clarify this matter quite clearly. The first is Aronofsky’s acquisition of the rights to the American adaptation of Satoshi Kon’s anime (Paprika) back in 2001, and it’s hard to believe that the sole purpose of this investment was honesty towards the Japanese and an irresistible desire to place Jennifer Connelly in a bathtub (Requiem for a Dream) and recreate a dramatic scene from Perfect Blue one-to-one.

The issue is complicated by the fact that Aronofsky steadfastly denies that Nina Sayers’s character was influenced by Mima Kirigoe’s story. When asked about Black Swan, he firmly responds:

There are certain similarities between these films, but Perfect Blue was not my inspiration. I was grappling with Swan Lake because I wanted to dramatize ballet.

Aronofsky has no problem praising the works of Pyotr Tchaikovsky and Fyodor Dostoevsky, citing them as the major influences on his most famous film. However, one cannot overlook the numerous borrowings from Satoshi Kon’s animation that Black Swan contains. Many. The open question remains how to classify these references. I warned about spoilers already, but I will do it once more – I will delve into the intricate plots of both films.

Perfect Blue is an outstanding film – Black Swan is too, in my opinion, though this verdict is not as widely accepted. Both titles certainly share the genre and the way its guidelines are executed, but the most ardent anti-plagiarism critics of Aronofsky point out similarities already at the stage of comparing the plot outlines, which – when appropriately crafted – seem strikingly similar:

Perfect Blue:

Mima Kirigoe is a young J-pop star who faces the chance to take the next big step in her career. To become a movie star, she has to sacrifice a lot, gradually losing her own self in the process.

How does Black Swan fare in comparison?

Nina Sayers is a young ballerina who faces the chance to take the next big step in her career. To become a prima ballerina, she has to sacrifice a lot, gradually losing her own self in the process.

Seeing these descriptions, one might prematurely judge Aronofsky as a plagiarist – but is it certain? As mentioned, they seem strikingly similar when appropriately crafted – this involves highlighting the similarities while omitting what differentiates both films. And there’s quite a bit of that. One might argue that changing one artistic field for another is a nuance – agreed. In this regard, the central theme is the pressure exerted on a young person by entirely new life situations. This loss of self in work and constant hallucinations that emphasize the protagonist’s hesitation are the main themes of both films, and in Perfect Blue, they seem to cry out for a return to the previous stage of the career – we have mirrors that show someone different from the person looking at them; the same happens with the reflection in the subway car window.

At this point, it is worth noting that while these scenes are seemingly identical, Kon and Aronofsky use them for entirely different purposes. The young J-pop star, at the manager’s urging, decides to leave the frivolous industry that has labeled her as a sweet and delicate girl. The fact that this is who she actually was and now has to change it intensifies Mima’s desire to return to singing – the manager, however, suggests something completely different, and at his urging, the girl agrees to a sex scene in the series she’s cast in and later a nude photo session – all against her will and as if to confirm the typical Japanese I cannot disappoint their expectations.

It’s completely the opposite for Nina – an incredibly talented ballerina and perfectionist who has the chance to become a prima ballerina in a completely new production of Swan Lake. However, to do this, she must understand that perfection is not just about flawlessly executing steps and figures but about losing herself in the dance in such a way that it sweeps the audience away. Genius and madness are separated by a very thin line, but so far, the well-behaved and orderly girl that Nina still is has not been able to even come close to this threshold. If she doesn’t, her life opportunity will be lost.

Both girls are heading in completely different directions.

At this point, the plots of both films clearly diverge, continuing to use very similar means of expression – and it is precisely the atmosphere-enhancing music by Clint Mansell and the dark cinematography by Matthew Libatique that should be “blamed” for the associations with Perfect Blue. Where Darren Aronofsky tells his own story, the allusions do not end.

Is the pressure that leads to (partial) loss of reality and gives filmmakers the opportunity to showcase the creation of dreamlike visions enough evidence to accuse him of borrowing? Both films evidently draw from Carl Gustav Jung’s psychological theories, giving us a complex picture of the relationship between who a person thinks they are and how their view of themselves changes under external influences. Only this and so much more.

In the pursuit of the truth about the borrowings, it seems significant that beyond the similarity of the main characters, which could equally well be pulled from their film worlds and swapped places, the creation of their surroundings is the essence of the differences. Is the motif of stress caused by new challenges merely a pretext for Kon to tell a story about how easily a defenseless person can be manipulated by someone close to them? While the central twist in Perfect Blue is the revelation of Rumi’s role in the chaos surrounding Mima, including using a mentally disabled man as a persistent stalker, in Black Swan, the starting point is precisely breaking the bonds that have shackled Nina for years – her mother (Barbara Hershey) is thus partially an equivalent of both Rumi and the Maniac (hence the visual references) but also an additional element of pressure that ultimately triggers Nina’s madness and genius.

Ultimately, it’s hard to disagree with the arguments of both sides – Aronofsky borrowed heavily from the story created by Yoshikazu Takeuchi and filmed by Satoshi Kon. However, it is not a repeat adaptation of the manga nor a remake of the anime. As a fan of both titles, I have a problem with evaluating them. They always evoke cross-associations for me – when I watch one, I think of the other, and vice versa. These similarities only gain proper perspective when you watch both films back-to-back. Then you don’t have to rely on faulty memory and its deceptive nature. I dare say that the similarity of Black Swan to Perfect Blue is based mainly on the central theme (not that rare in cinema) and a multitude of visual references, which in themselves do not mean plagiarism – at most a tribute (especially since Aronofsky has the rights to adapt it). The problem is that after the screening, it is the image, not the story (which memory fades over time), that stays in our heads.

Whether the New Yorker genuinely intended to pay homage to Tchaikovsky and Dostoevsky, but his thoughts wandered to Perfect Blue by accident, eventually engulfing him entirely, we may never know if we don’t take his word for it – he denies the influence of Mima Kirigoe’s story. It is therefore difficult to go beyond the two most likely scenarios that could have led to the creation of Black Swan: Aronofsky either overdid the number of allusions to the cult anime in his original work – he is known for that – or he truly intended to make a remake of Satoshi Kon’s film, but during production, he let his imagination stray too far, leading to a completely new, separate creation. The final proof that the first version of events is closer to the truth seems to be the information given by Masao Maruyama – producer of the original Perfect Blue – in an interview with Dazed Magazine.

Maruyama’s words clearly indicate that he and Kon had been in discussions with Aronofsky for a long time. According to him, while Black Swan is very interesting, it shares only a few scenes and the theme of obsession and loss of identity with Perfect Blue—this is not enough to consider it an adaptation. That adaptation, supposedly, is yet to come.

Adding a somber note to the whole issue is the fact that filming for Black Swan took place six months before Satoshi Kon’s death from pancreatic cancer. I wouldn’t have minded if this inspiration had been acknowledged explicitly—the film could have become a tribute to the master, similar to how Alejandro González Iñárritu made The Revenant a living monument to Andrei Tarkovsky. If only Aronofsky didn’t persistently deny it…

Written by Damian Halik.