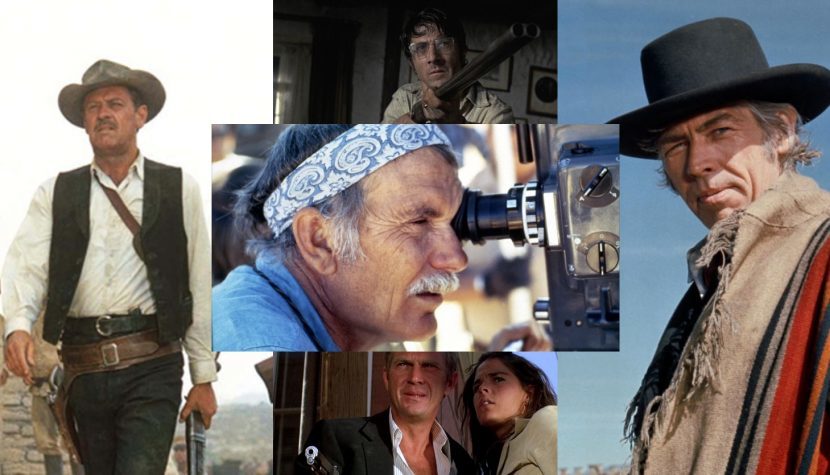

Times have changed, he hasn’t… SAM PECKINPAH’S film ranking

Sam Peckinpah (1925-1984) earned his position solidly. He started almost from the bottom in the television industry and gradually climbed upwards, intriguing his colleagues with his unparalleled imagination and creative inventiveness, but also annoying with his self-destructive lifestyle (alcohol addiction). To achieve excellent results on the screen, behind the scenes should stand not only professionals, but also people with iron patience. Fortunately, there was no shortage of such in Hollywood, which resulted in the creation of great classics that make up the first seven (half) of this list. The director, to whom the nickname Bloody Sam adhered, managed to gather around him a group of regular actors, unofficially known as Sam Peckinpah’s Stock Company (after The John Ford Stock Company). Its members included: R.G. Armstrong, James Coburn, Ben Johnson, L.Q. Jones, Warren Oates, Slim Pickens, Jason Robards and Dub Taylor.

7. The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970)

The screenplay by John Crawford and Edmund Penney became a new challenge for The Wild Bunch creator, testing his skills in a new genre – the western ballad. His most famous film in this vein is Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973), but already three years earlier his film fulfills the premise of the ballad genre perfectly, what the choice of appropriate music plays a large part. Both pictures contain original music seemingly incongruous to the world of the Wild West, but creating an unreal atmosphere around realistic events. With a sense of humor and nostalgia, the director told the story of Cable Hogue (Jason Robards), who, abandoned in the wilderness by his associates, found his way to a water source, becoming a businessman. He is accompanied by prostitute Hildy (a great role by Stella Stevens), for whom the relationship with the title character is a chance to change her previous lifestyle. The couple is watched by God in the form of an itinerant preacher (David Warner), but will Hogue be able to take advantage of all the opportunities presented to him by fate?

The Ballad of Cable Hogue testifies to the wide range of skills of the director, who, even working within a single genre, was able to create diverse works. The film is moody and romantic, filled with tenderness and nostalgia, but when necessary – also rough and frivolous. The musical setting (melodies by Jerry Goldsmith and songs by Richard Gillis) is interesting – as in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), the three positive characters have their own musical theme. The cast, headed by Jason Robards, is great. The actor was already approaching his fifties, but his film career was just beginning to gain momentum (at that point he was a respected stage actor with a Tony Award in 1959). He gave the character of Cable Hogue the traits of a sensitive, somewhat lost hero.

Set in the declining period of the Wild West, the tragicomedy presents a turning point in American history in a unique way – the moment when a new reality represented by automobiles is coming, and streets and tall buildings will be built on desert land in the future. The pride of a lonely individual intoxicating himself with freedom is confronted with the pride of the coming civilization bringing new inventions, creating a new world on old foundations. The Ballad… is perfectly balanced, containing in the right proportions elements of comedy, western, musical, romance and social commentary, so it never falls into cliché, and the filmmakers were careful to avoid schematic solutions. Thus, it isn’t only one of Peckinpah’s most original works, but also one of the most unusual American westerns.

6. The Getaway (1972)

An adaptation of Jim Thompson’s novel (The Getaway, 1958) by Walter Hill, now a cult director of action films such as The Driver (1978), Southern Comfort (1981), and 48 Hrs. (1982). Walter Hill adapted The Getaway twice – the second version (1994) was directed by New Zealander Roger Donaldson, and starred Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger. For me, however, Sam Peckinpah’s film with Steve McQueen is the one I return to more often. Thanks to the masterful direction, the film is like a piece of music, from which it only needs to remove one note to lose its proper sound and rhythm. A brilliantly played out story addressing issues of trust, freedom, and the power of money. What surprises is the subtlety with which the director presented the relationship between the two main characters. It contrasts brilliantly with the nervousness present in the later, more dynamic part of the film.

Thanks to the personalities of Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw, the duo of protagonists is charismatic, ambiguous in its assessment. It arouses sympathy, but also worries because of the emotional coldness that beats from it, which seems to suggest unpredictable characters fighting an internal battle. McQueen played the ex-con McCoy, who can enjoy freedom thanks to the support of a powerful boss. But in this world no one acts selflessly, so freedom comes at a price. McCoy was taken out of prison to rob a bank and, of course, share the loot. Both the bank action and the division of the loot don’t go according to plan. The power of the dollar makes conflicts arise and everyone can only trust themselves. Unlike in the production of a film, where to create a solid yet commercial work, the filmmakers had to trust each other. Peckinpah was not easy to trust, he was an unruly filmmaker, destroying his body with harmful stimulants, additionally he had box office failures, such as Junior Bonner, which premiered in June 1972. The Getaway hit the screens six months later, achieving commercial success and somewhat rehabilitating the director in the eyes of the audience.

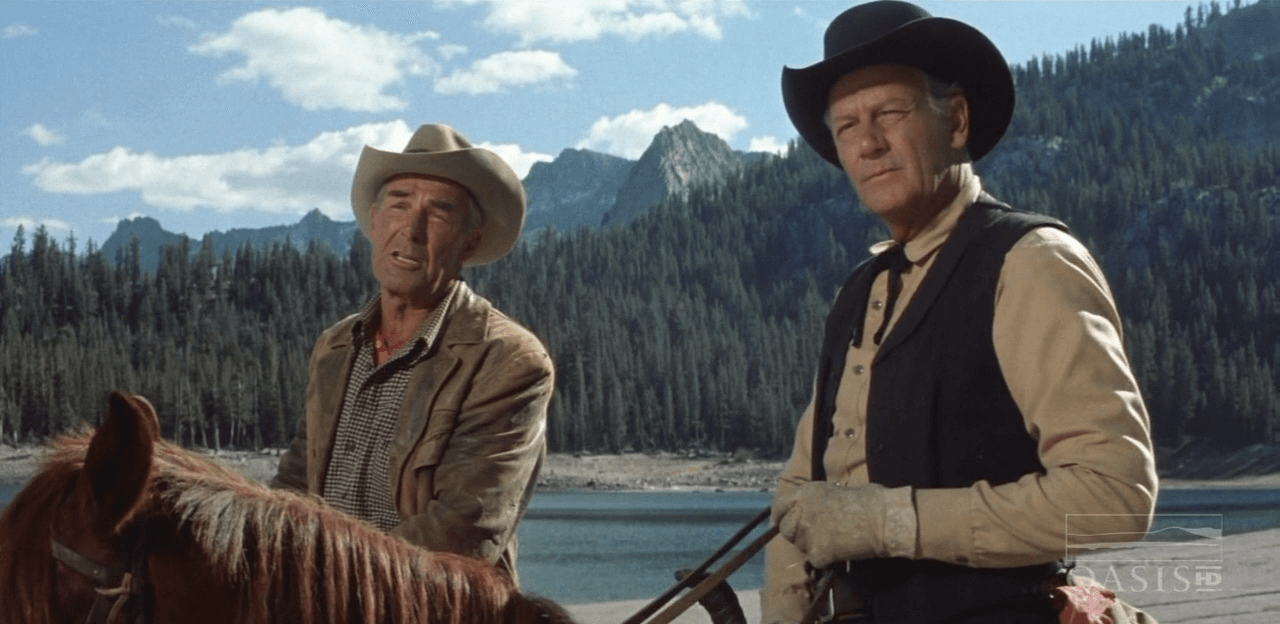

5. Ride the High Country (1962)

In 1956-1960 Randolph Scott starred in seven interesting psychological westerns by Budd Boetticher and was preparing to end his career. So he was looking for a suitable role to say goodbye to cinema. When a script signed by TV auteur N.B. Stone Jr. came into his hands, he didn’t think an above-average film could come out of it. The story of two old buddies transporting a cargo of gold through dangerous terrain seemed very classic, similar to the plot of Vera Cruz (1954), but with an emotional force comparable to B-grade cinema. At the time, Randolph Scott didn’t yet know Sam Peckinpah, a young gifted filmmaker with an offbeat imagination who knew how to make timeless cinema out of a classic story. When the 64-year-old actor saw the completed film, he made the decision to retire, as he was convinced he would never play a better role again. Interestingly, his seven years younger set mate, Joel McCrea, also decided to end his career at the time, but returned to the set in the next decade.

In Europe, the film is known as Guns in the Afternoon. It begins rather comically and uncharacteristically. A rider arrives in town and sees a cheering crowd. He smiles, thinking it’s in his honor, then it turns out that he has intruded on the race track. An unusual race – riders on horses try to catch up with the camel rider, but to no avail. Horses, having a big part in the conquest of the Wild West, lose to Lawrence of Arabia’s desert mount? This could only mean one thing – the western is losing to the exotic, a way must be found to revive the genre, to make it more dynamic, to take a different path. The journey, which is the main theme of the plot, is already taking place on horseback. But it is not the horses that turn out to be the weak point, but the people. Among the characters is a young man who rode a camel in the prologue. A swindler or dodger, or maybe just a man representing the new times – at first despising the old bores, but gradually noticing the honor and dignity inherent in them. He is like an alter ego of the director – a person who respects classic westerns, but nevertheless wants to pour fresh blood into this old convention. In turn, the two protagonists (McCrea and Scott) are two faces of one man torn between honesty and cunning, a sense of duty and a selfish desire to enrich himself. A woman (Mariette Hartley’s excellent debut) was interestingly portrayed in this masculine world – she performs a similar function to the cargo of gold transported by the protagonists, that is, she is also desired by almost all men, treated as an object whose possession brings happiness.

The original title Ride the High Country can be understood literally, as a journey through the mountain range in the Sierra Nevada, but also metaphorically – as a ride to enrich oneself, to achieve high gains, a quest for happiness, which are symbolized by the cargo of gold and the girl looking for a man. One more interpretation fits the film. Since the action of this western is set in the twilight period of the Wild West, ride the high country can mean the aspiration of mankind to create a new civilization, without horses, but with cars and streets, while erecting monumental buildings on fertile land. The death of one of the main characters in the finale is a symbol of transformation, the rebuilding of the country, because in order to build something new, some part of the old world must be put to death.

After the success of Ben-Hur (1959), the MGM label invested in big shows and the monumental How the West Was Won (1962) was in the pipeline. Few had high hopes for Peckinpah’s little western. The then president of the studio, Sol C. Siegel and producer Richard E. Lyons trusted the young director, gave him free rein to tweak the script, work with actors and even edit (significant for the director’s future career was his collaboration with Frank Santillo, who taught him editing tricks). Years later, Ride the High Country became one of the most important films of the decade and is considered a turning point in the history of the Wild West stories. Critics and film scholars referred to it as the first revisionist Western (also called the anti-Western). Along with John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), he set the path for the further development of the genre. On this new path, westerns continued to enjoy success, but increasingly moved away from American mythos, taking very different forms – iconoclastic satire (Little Big Man, 1970), realistic drama (McCabe & Mrs. Miller, 1971) or nostalgic ballad (Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, 1973).

4. Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

The finale of The Getaway, set near the Mexican border, is somewhat symbolic. Mexico for Sam Peckinpah symbolized an escape from the Hollywood lifestyle. Here he hoped for creative freedom, because he loved Mexican culture and it inspired him the most. His wife, actress Begoña Palacios, was Mexican and he made four films in her native country: Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. The latter is an excellent reworking of Western templates into a contemporary romantic-sensational story. The screenplay was developed by Gordon T. Dawson together with Peckinpah, based on an idea by Frank Kowalski. Work on the text took almost three years and began already on the set of The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970). The director managed to gain creative freedom by working with Martin Baum, founder of the independent production company Optimus, affiliated with United Artists.

Surrounded by an army of loyal men, a wealthy landowner known simply as The Boss (El Jefe) offers $1 million for the head of a man who has made a bastard child of his daughter and thus tarnished the family’s honor. This starting point is a pretext to show how primitive and greedy person has to be to join for the money in a dirty and dishonorable game. Alfredo Garcia’s head is buried with the rest of his body in a Catholic cemetery, as the man died in a car accident. This is learned by Bennie, a bar employee living modestly, who is visited by bounty hunters looking for Garcia dead or alive. Bennie is the main character, but he’s really no different from these bounty hunters – he too thinks in terms of “how much money can be made” rather than “does it make sense.” Knowing that Garcia is dead, he throws his own offer to the searchers – for the right sum he will find Alfredo and bring his head. In time, however, he sees what a swamp he has gotten himself into through his own audacity. The fly-covered stinking head in a jute sack symbolizes the worst human traits – brain deadness, moral decay, nasty insides. Man is just a piece of rotting meat, the director seems to be saying. When Bennie’s girlfriend throws him a question- accusation: “Do you want to desecrate a grave?”, he replies: “There ain’t nothing sacred about a hole in the ground or the man that’s in it. Or you. Or me”. Thrown in the right situation, the comment provokes reflection on the human condition.

Despite appearances, the film is romantic and touching. Bennie does everything he does for a woman. Despite the fact that she betrayed him, he is able to forgive her and wants by all means (even over dead bodies) to provide her with a decent future. But as they say, “hell is paved with good intentions.” The story is gripping because it is brilliantly handled both at the stage of the script (accurate dialogues, surprising twists and turns, a determined and persistent anti-hero) and directing (staging of action and violence scenes, leading the actors in such a way as to give them psychological depth). On the acting side, the film is also flawless – Warren Oates is a master of the background, but here he played the main role and performed capably. Bennie’s fate is actually a brutalized version of the director’s biography – Bloody Sam’s career is a string of turbulent and obstacle-filled fates of a social outcast. Visually, this film differs from Peckinpah’s other works. The collaboration with Mexican cinematographer Álex Phillips Jr. resulted in a hellishly bleak and raw image of Mexico on the screen. Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia is a very personal film by Sam Peckinpah, it was noticed already in the 1970s – the director managed to put his authorial stamp on this picture.

In the context of this work, it is worth mentioning the book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time and How They Got That Way, published in 1978, signed by Harry Medved and Randolph Lowell Dreyfuss. This publication included the Peckinpah production discussed above, and in addition to patently weak films like Robot Monster (1953), Swamp Women (1956), Santa Claus Conquers the Martians (1964) and The Conqueror (1956, the one with John Wayne in the role of Genghis Khan) also made it to the infamous fifty: Alfred Hitchcock’s Jamaica Inn (1939), Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible (1944), Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970) and even Richard Donner’s The Omen (1976).

3. Cross of Iron (1977)

Completed in 1976, Cross of Iron, like Peckinpah’s three previous films, was not a profitable production, but is quite rightly considered today as the last great work in the director’s career. The days of popularity of films about World War II were already slowly passing, and from 1978, with the release of The Deer Hunter, Vietnam would become a carrying subject. At least this was the case in American cinema. The makers of Cross of Iron were targeting the European market, where, by the way, Sam Peckinpah was more appreciated than in the US. The screenplay was based on Willie Heinrich’s novel The Willing Flesh (1955), quite freely inspired by authentic events, in which he participated Wehrmacht NCO Johann Schwerdfeger. The main adaptor of the book was Julius J. Epstein, whose credits include Casablanca (1942), one of the most important films of American cinema.

Such a work had to be created by the hand of a sober filmmaker, and although Peckinpah wasn’t one of those, he set aside tequila and cocaine to present his vision of World War II. Cross of Iron isn’t only a condemnation of the war, but also of human attitudes: making a career at the expense of dead soldiers, valuing people based on the number of medals and stars on their uniforms. To make the anti-war message stronger, Prussian pride and honor were juxtaposed with brutal wartime realism, and propaganda material from the prologue formed the framework of the story along with a satirical epilogue in which Sergeant Steiner bursts out laughing out loud. Without moralizing, escaping into the grotesque, the director presented the absurdity of war life, showing the superiority of the soldier over his commander.

The main virtue, thanks to which the film perfectly defends itself years later, is a two-pronged approach to war cinema. On the one hand, showing psychological, typically human aspects to accentuate the anti-war message. But on the other, presenting the battlefield in the form of action cinema, attaching great importance to the spectacularity of the battle scenes. The primary motif is the conflict between feldwebel (sergeant) Steiner and hauptmann (captain) von Stransky, two German soldiers representing different attitudes related to war, honor, morality and the meaning of military medals. James Coburn and Maximilian Schell have played the roles of their lives here. And the fact that they don’t speak German doesn’t at all diminish the film’s credibility or the strength of its message. In the same decade sequel entitled Breakthrough (1979) was made in the Austrian outdoors. Its director was Andrew V. McLaglen, and the role of Sergeant Steiner was played by Richard Burton. This film looks very poor even without comparison to the original. Andrew V. McLaglen has much more interesting productions to his credit, such as the action war movie classic The Wild Geese (1978) and the Peckinpah-esque western The Last Hard Men (1976).

2. The Wild Bunch (1969)

Between Major Dundee (1965) and The Wild Bunch (1969), Sam Peckinpah made a less than 50-minute television production for ABC called Noon Wine (1966). He wrote the screenplay based on a story by Katherine Anne Porter, and starred Jason Robards and Olivia de Havilland in the lead roles. After production difficulties on the sets of Major Dundee and The Cincinnati Kid, which was eventually directed by Norman Jewison, the making of Sam Peckinpah’s next theatrical film was in question. Only positive critical reviews of Noon Wine improved the director’s image in the industry somewhat. Producers Kenneth Hyman and Phil Feldman of Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, which ran from 1967-1970, approached him with an offer to write a script based on an idea by Walon Green and Roy N. Sickner. The company had previously financed Bonnie and Clyde (1967, directed by Arthur Penn), a groundbreaking work in terms of showing violence on screen, so no one blocked the production because of the high dose of screen brutality. The result was one of the strongest westerns of its time. In terms of showing male loyalty, it brings to mind the works of Howard Hawks, but devoid of fairy-tale heroism – here heroism means death and doesn’t involve the conquest of a woman.

“The Wild Bunch” was called in the Wild West the gang led by Bill Doolin and Bill Dalton, active in the last decade of the 19th century and engaged in robbing banks, stores and trains. From this inspiration (but also from historical accounts concerning Pancho Villa) was born the story of the outlaws’ pursuit from Texas to Mexico in 1913, when revolutionary uprisings were gripping Mexican soil. William Holden, in the role of the bandleader, heads from one hell to another amidst wheezing bullets and falling corpses, smelling death at every turn. What values is the fight for and what is a man capable of in order not to lose it? Do the rules of the code of honor still have any meaning? These questions were also asked in the late 1960s in the context of the Vietnam War. Peckinpah himself, speaking of the violence in the film, stressed that it stemmed precisely from Americans’ growing frustration with the Vietnam conflict. He wanted to show the violence differently than in classic westerns and TV productions, with more realism, far from playing sheriffs and robbers to make the viewer’s gut twist. It didn’t have the intended effect – viewers treated the scenes of violence as the film’s greatest attraction, not as something negative.

The film wasn’t the most box office western of the year (better results were achieved by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and True Grit), but for an age-restricted film it can’t be called a failure. Especially since critics were also delighted, comparing The Wild Bunch to the films of Akira Kurosawa and even Citizen Kane, and ranking William Holden’s role among the best of his career. Peckinpah made a breakthrough here not only in terms of on-screen violence, but also in terms of filming technique, particularly when it came to editing and sound design. Film editor Louis Lombardo demonstrated an extraordinary visual sense in processing the action scenes. On the other hand, the sound engineers, after consulting with the director, didn’t use the Warner Bros. sound base to match gunshot effects, but created a separate effect for each type of weapon. Lucien Ballard’s outdoor cinematography and Jerry Fielding’s music were also appreciated. To this day, it remains one of the most important achievements of American cinema and one of the best westerns ever made.

1. Straw Dogs (1971)

It’s interesting that TV filmmaker Daniel Melnick, who had already worked with Peckinpah on Noon Wine (1966), was in charge of producing the film. And the ABC television company was also a major investor in Straw Dogs. At the same time, the film was both in content and imagery so appalling that no TV station at the time would have dared to show it. Even in the cinema it raised moral questions, yet in the same year such pictures as Dirty Harry, Get Carter and A Clockwork Orange hit the screens. The material for the film was provided to Peckinpah this time by Gordon M. Williams, author of the novel The Siege of Trencher’s Farm (1969). While David Zelag Goodman, co-author of the excellent western about cowboys, Monte Walsh (1970), helped Bloody Sam develop the script.

In a Cornish setting, we observe a mismatched pair of characters – he is an intellectual, she a sexy blonde. This mismatch makes there is a kind of emptiness in this relationship and both don’t feel full happiness. However, they have what many dream of – relative security and peace. Until, however, fate prepares for them an unpleasant test of character. Violence enters their orderly world in the form of two human types. The first is a mental cripple who has trouble distinguishing between right and wrong, is capable of unintentionally hurting people and also unwittingly brings misfortune to the pair of main characters. The second type is a vengeful community, hungry for blood like a herd of wild animals, using any pretext to attack. When the safety of the main character and his wife is threatened, the hitherto hidden ferocity of the character will come to the surface.

The allegorical title Straw Dogs reveals the meaning of the work. The act of violence is a ritual, and people are only a tool in this ritual, straw dogs. That is, they pretend to be animals in order to defend themselves from what they perceive to be evil (and paradoxically becoming evil themselves), and once they unload their aggression, they become human again and life returns to normal. Excellent here are the performances of the two protagonists, Dustin Hoffman and Susan George. They have created ambiguous characters whose reaction to violence is believable. With acting that suggests inner experiences and moral doubts, it gets heated. The viewer’s comfort and patience have been put to the test and it is difficult to remain indifferent to the events depicted on the screen. This is a film brilliantly photographed using natural lighting (this is the beginning of Peckinpah’s fruitful collaboration with British cinematographer John Coquillon), but the nervous atmosphere and emotions were also brought out by masterful editing (among the editors was Roger Spottiswoode, later director of one Bond film, Tomorrow Never Dies).

The film divided critics – the efficient execution was appreciated, but disagreed with the overall message, accusing the director of misogyny and the depiction of rape as a punishment for a woman’s ability to manipulate sex appeal. 40 years later, a remake was made, titled the same as Peckinpah’s film, so it wasn’t even an attempt to re-adapt the book, but an attempt to cash in on the controversial title. Few people know, but not long after the film of Bloody Sam, there was a Turkish adaptation of The Siege of Trencher’s Farm, titled The Eagle’s Nest (1974).