The most interesting VIKINGS MOVIES. A fascinating journey in the footsteps of the Northmen

Of their many conquests, the Vikings have had the most trouble conquering cinemas and television. But they’ve had some notable successes in the past decade. After the six-season-long series Vikings (2013-2020), the subject was taken up by one of the most acclaimed filmmakers of modern cinema, Robert Eggers (The VVitch: A New-England Folktale, The Lighthouse). His The Northman was another artistic success for the director, but with a budget of more than $60 million it turned out to be a commercial disappointment. Historical pictures, even those of the highest quality (e.g., Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel), are not what most interest the mass audience these days.

From the Fury of the Northmen, O Lord Deliver Us!

Movies about Vikings are a very narrow strand of cinema (especially when compared with swashbuckling pirate movies), so Eggers’ new film hasn’t very strong competition. But there are a few special cases that can compete with it, although they are not more widely known (here I’m thinking primarily of Icelandic productions from the 1980s, because if any nation can be considered specialists in Viking climates, it’s Icelanders). This summary isn’t in the form of a ranking, but a chronological list of the 10 most interesting film adaptations of the legends of the Normans, as the Vikings were called in Western Europe (or the Varangians – in Eastern Europe). For the record, the word Vikings accurately means warriors going overseas to plunder, rape and murder, and can refer to more than just northerners (for example, in the 1967 film The Viking Queen, this term refers to the Celts). For obvious reasons, this article considers only stories about Nordic warriors.

Related:

The Viking (1928), dir. by Roy William Neill

A film produced by Herbert T. Kalmus, president of the Technicolor corporation that revolutionized cinema. The days of color pictures came after the sound stage, but as early as the silent cinema era there was experimentation with color. One such groundbreaking work is The Viking, directed by Roy William Neill, which was first (in 1928) released as a silent film, but when MGM studio executives were impressed by the innovative visuals, they decided to distribute the film in sound. The new edition premiered in 1929 and wasn’t fully audio – viewers still had to read the boards with descriptions and dialogue, but other sounds (the roar of the MGM lion, the music recorded on the disc, the sounds of the crowd, the sounds of sword duels) could be heard in the cinema. However, it was the use of color that made an electrifying impression at the time – already in one of the opening scenes we have red blood stains dripping onto the book after a Viking murders one of the Englishmen.

The intrigue was taken from Ottilie Adelina Liljencrantz’s book The Thrall of Leif the Lucky: A Story of Viking Days (1902). The story begins in England and continues in Norway, then Greenland, to end with the discovery of America. Lord Alwin (LeRoy Mason) of Northumbria is abducted and taken into Viking captivity. He is bought by Helga Nilsson (Pauline Starke), an orphan in the care of Viking Leif Ericsson (Donald Crisp). An important theme of the picture is the conflict between the pagan beliefs espoused by Erik the Red (Anders Randolf), the explorer of Greenland, and the Christianity professed by his son, Leif. Of course, there is more legend than truth here, the Vikings wear horned helmets, and the construction of the stone tower in Newport, which still stands today, is attributed to Leif according to the theory propounded by Danish historian Carl Christian Rafn. The breakthrough made by the film is no longer very significant today and the film has disappeared somewhere in the abyss of oblivion. Also working against it’s the not very convincing side of the plot – it’s a story with a banal message about the power of love supported by faith in the “only right” religion.

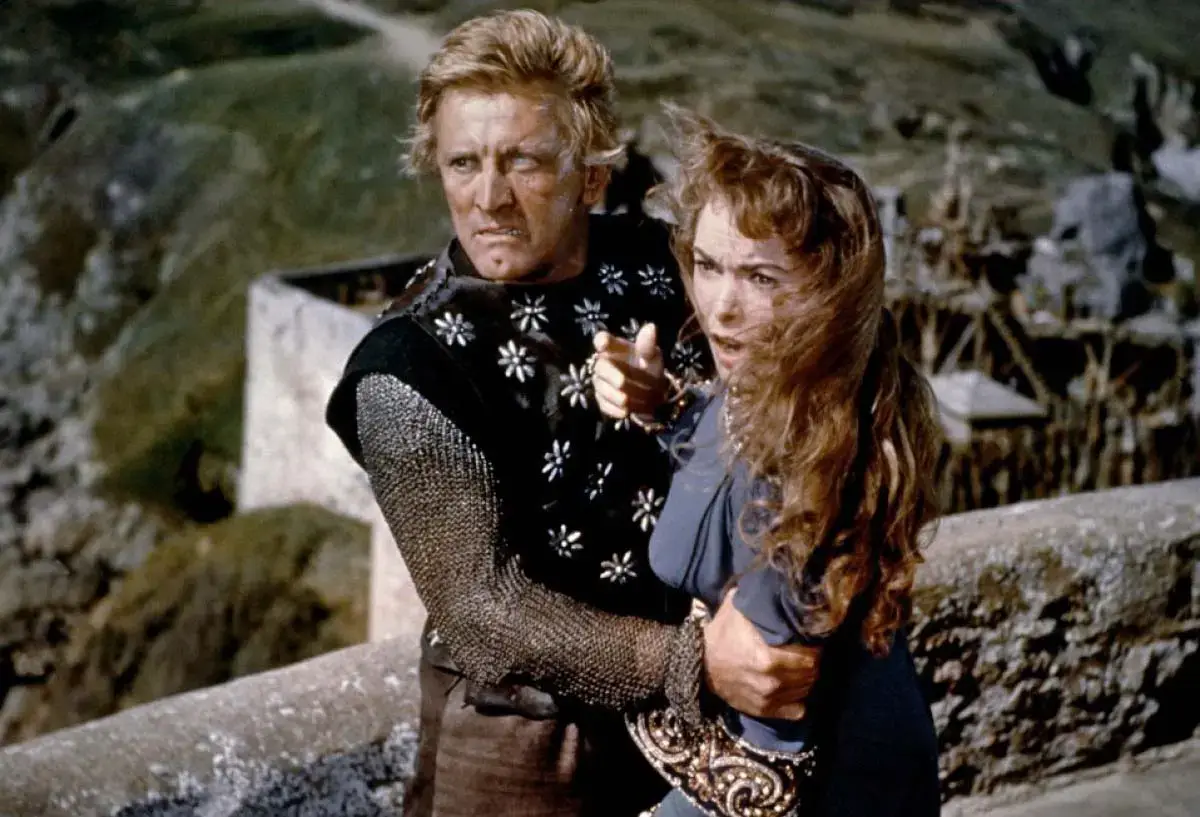

The Vikings (1958), dir. by Richard Fleischer

In the 1950s – as part of a series of historical dramas shot on a grand scale – there was, among others, Prince Valiant (1954), directed by Henry Hathaway and based on a comic strip by Harold Foster. However, it received mixed reviews and ultimately failed to recoup the production costs put into it. The making of another Viking film thus came under question, but a risk was taken when Edison Marshall’s book The Viking (1951) reached the desk of Hollywood producers. Adaptation, under the direction of Richard Fleischer, was shot in a modern Technirama system, so the colors were enhanced, emphasizing the beauty of the locations: Norway, the Lima Fjord in Croatia or Brittany in France. This time the effort paid off – it was a hit both in the U.S. and abroad. And although critics accused it of being closer to a fairy tale or western than a racial historical production, it became for many years a model of how films about Vikings should be made.

The Norman invasion led by Ragnar (Ernest Borgnine) and the resulting death of the Northumbrian king become the pretext for the usurper and tyrant Aella (Frank Thring) to take the throne. The widow of the previous king, Enid (Maxine Audley), is expecting a child – a potential future claimant to the throne of Northumbria. The child’s real father, however, is Viking chieftain Ragnar. After twenty years, a meeting occurs between the slave Eric (Tony Curtis) and the Viking Einar (Kirk Douglas), who share the same father, but do not yet know that the same blood flows through their veins. From the first glance, they feel hatred for each other – Eric attacks Einar with a predatory falcon, which deprives him of an eye, as a result of which Einar and his father condemn the slave to a slow death – he is thrown to the crabs to eat. The conflict is exacerbated when they both fall in love with Princess Morgana (Janet Leigh).

In a way, it resembles a fairy tale in the style of Greek myth with a fate weighing down on the characters. One also senses an affinity with classic westerns – conquests of western lands, fraternal conflict culminating in a duel, a main character resembling a western good bad guy who, despite his evil deeds, isn’t the murderer type, but an honorable man. The final duel between the brothers is magnificent in terms of choice of location, realization and choreography by French classical fencing master Claude Carliez. In the wake of the film’s success, the Tales of the Vikings series (1959-1960) was created, telling the adventures of Leif Erikson. The series was co-produced by Elmo Williams, editor of Fleischer’s film and second unit director (responsible for the action scenes). In turn, the cinematographer of the work in question, Jack Cardiff, shot the colorful show The Long Ships (1964) in Yugoslavia. The production has its fans, although the person writing these words isn’t one of them. On the wave rising Viking ships also benefited the Italians – in 1961 alone they were made in Italy: Erik the Conqueror (1961) by Mario Bava, The Last Viking (1961) by Giacomo Gentilomo and Tartars (1961) by Richard Thorpe, where the Vikings are the opponents of the titular barbarians.

Knives of the Avenger (1966), dir. by Mario Bava

Like many Italian genre filmmakers, Mario Bava defended himself against being pigeonholed into one type of movies. After the success of Black Sunday (1960), he became a master of gothic horror, and while he confirmed this by returning to the genre, he also tried to experiment with other types of entertainment. Often these were cinematographic experiments, as in the case of Erik the Conqueror (1961), Bava’s first film about Vikings. The plot and some of the ideas were stolen from Richard Fleischer’s The Vikings (1958), but visually it is an exceptional work – you can see that it was shot by an artist who can work wonders with camera and light. By plot, however, I think Bava’s second Viking picture, Knives of the Avenger (1966), is a much more interesting show. This doesn’t mean that it’s an original work – one can still sense the influence of American cinema, this time the western Shane (1953) by George Stevens.

A woman named Karin (Elissa Pichelli) and her son listen to the forecast of an old prophetess invoking the name of the god Odin. There is both comfort and warning in her words. She heralds hope, for the woman’s presumed dead husband, King Harald (Giacomo Rossi Stuart), is alive and will soon return to her. But it also warns that the devil doesn’t sleep, so it is advisable to flee, keeping close to the sea so that the water will wash away the footprints. Their enemy is the cruel Hagen (Fausto Tozzi) wishing to marry Karin to take over her clan. Hagen’s men quickly find the woman’s hideout, but their struggle with the helpless lady is interrupted by a mysterious “horseman from nowhere” (Cameron Mitchell), who is particularly good with knives. The stranger is plagued by demons of the past – in a murderous rampage of revenge he once killed innocent people, and his name Ator inspired fear. Now he longs to right the wrongs, and the gods give him that chance by putting Karin and her son in his path.

Interestingly, Leopoldo Savona was hired to direct the film, but he was not up to the challenge. Mario Bava was pulled in to rescue the project, and he wrote the script from scratch and completed the film in short order. Fast and cheap are not words one associates with an epic historical or adventure production, so on the surface it doesn’t sound promising. And if anyone expects spectacular battle scenes and conflicts pulled from the pages of medieval history, they will be disappointed. And yet the film defends itself perfectly, offering a fascinating tale bordering on a dark fairy tale and an intimate story about attempts to atone for past sins. Knives of the Avenger is an example of Mario Bava’s genius – proof that to make a good film you need: a solid workshop, the soul of an artist, creative energy, and only on the next money are needed.

Alfred the Great (1969), dir. by Clive Donner

The biography of one of the most eminent English rulers was made by Clive Donner, who had no experience in making big-budget pictures. The result was an unconventional work based on the relationships between the characters, rather than showy battles. However, it managed to avoid an annoying theatrical manner and enter the battlefield as well. Scenes showing soldiers in a Spartan phalanx are impressive, but in addition to the historically confirmed clashes between the English and the Danes, human attitudes in the face of crisis situations were also important to the filmmakers. Instead of a sword in his hand, Alfred would rather hold a cross and raise prayers, because he felt his destiny was to become a priest. But when his country is attacked by northerners, he is forced to change his life plans and takes on the role of a war strategist, a role in which he excels. As king of Wesssex, he doesn’t stray too far from the priestly ministry, because religion is everywhere. The conflict between two countries with different customs is also a battle between two demiurges: the Christian God and the Nordic god of war, Odin.

The screenplay is an adaptation of Eleanor Shipley Duckett’s book. Screenwriter James R. Webb and producer Bernard Smith co-created the successful historical westerns How the West Was Won (1962) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964), made for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. This time they reached into European history, and set the film in County Galway, Ireland. Unlike the great Alfred, the filmmakers failed miserably. Both in the clash with critics and the public, the film didn’t stand a chance. Although today it can be singled out as an interesting representative of the British costume drama of the 1960s, one must also admit that it has its weaknesses, evident, for example, in the underdeveloped dialogues. It’s interesting to note that the film featured the wife of playwright Harold Pinter, Vivien Merchant, who doesn’t speak any lines here – she refused to deliver sentences from the script due to their low quality.

Outlaw: The Saga of Gisli (1981), dir. by Ágúst Guðmundsson

Gísli Súrsson is the protagonist of an Icelandic saga set in the 10th century, telling the story of blood ties that are cut by hatred, jealousy and the harsh law of revenge. Gísli, along with his brother Thorkell and two brothers-in-law – his wife’s brother, Vésteinn, and his sister’s husband, Thorgrímur – try to make a blood pact, but a conflict arises that destroys the relationship. Vésteinn is killed in his own pallet, and Thorgrímur is accused of the murder. Soon death also befalls Thorgrímur, and because of this, Gísli becomes an outlaw man, pursued like a wild animal. When the Viking isn’t participating in a looting expedition or taking part in a battle, he seeks conflict within his own clan. Lacking a common enemy, blood ties cease to matter, as the blood of the warrior flows through the Viking’s veins.

When the Icelanders took on the Nordic sagas, the result was a remarkable, almost naturalistic work, providing an interesting counterbalance to Hollywood super productions. In addition to fairly realistically depicted rituals (mainly funerals), there are also ideas that have little to do with attention to realism, such as an ice hockey match. The Icelandic outdoors is shown amid both greenery and snow, which is also meant to emphasize that relationships between people change as quickly as the seasons change. The film brings out the best in the sagas for portraying a credible story from the ancient, already semi-legendary history of the North. Ágúst Guðmundsson’s picture could have become a model for many filmmakers interested in this fascinating period of history, but actually only one filmmaker decided to follow this path. This was Hrafn Gunnlaugsson, author of the excellent The Raven Trilogy.

When the Raven Flies / Revenge of the Barbarians (1984), dir. by Hrafn Gunnlaugsson

When Harald Fairhair after the unification of the Norwegian tribes became ruler of all of Norway, many of his opponents took to the sea in search of refuge. Iceland proved to be an ideal hideaway, where they could raise a family and farm in peace, away from big politics. However, the warrior’s past has earned him many enemies and it’s not easy to escape revenge, and a flying raven heralds a brutal and dishonorable death. Thord attacked Ireland twenty years earlier, plundered treasures (mostly silver) and killed many of the inhabitants. The son of one of those killed arrives in Iceland without revealing his name – he is simply called Guest (played by Jakob Thór Einarsson). His goal is to avenge his father and find his sister, who was kidnapped by the Vikings. The Guest’s plan is to decides to play two rival groups against each other – Thór (Helgi Skúlason) and Erik (Flosi Ólafsson).

The raven of the title is a Norse mediator between the human and divine worlds, bringing news to Odin, the greatest of the gods. The director drew inspiration from the films of Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone, and an association with the plot of Yojimbo (1961) and A Fistful of Dollars (1964) is immediately apparent. But the style is also far from Hollywood’s depiction of the darkness of the Middle Ages. Leone’s western inspiration is most evident during the final duel, when Guest, clad in armor, tries to approach the enemy and is attacked with arrows. The classic, not to say banal, plot has been ingeniously adapted to the realities of medieval northern Europe and enriched with local folklore. The atmosphere is brilliantly built by the Icelandic outdoors and the film’s seemingly incongruous repetitive music (Sigvaldi Kaldalóns’ piece Á Sprengisandi was used as the main theme). Hrafn Gunnlaugsson capitalized on the film’s success and the audience’s interest in Iceland’s medieval history by making two more Nordic stories. These works are also worth including in this article, because despite their similarities they differ a lot and complement each other perfectly.

Trees Grow on the Stones Too (1985), dir. by Stanislav Rostotskiy, Knut Andersen

Soviet-Norwegian co-production based on Yuri Vronsky’s novel Extraordinary Adventures of Kuksha from Domovichi. Bright-haired young man Kuksha (Aleksandr Timoshkin) is taken prisoner during an attack by Norwegians on Gardarika. Thorir (Thor Stokke), the leader of the invaders, however, sees in him the makings of a warrior, so he adopts him. The boy harbors hatred for the Danes, who slaughtered his relatives before the Norwegians arrived. But the motive of revenge turns out to be less important than the motive of longing for the homeland, also important are the themes of freedom and happiness, their meaning, appearances, using them to enslave people. Kuksha is given a new name, Einar the Lucky, falls in love with a beautiful royal daughter named Signy (Petronella Barker), and his rival becomes the battle-hardened berserk Sigurd (Thorgeir Fonnlid).

Russian medieval anthropologist Aron Gurievich, among others, was a consultant on the film, and there was some effort to do justice to the era. But it is largely a youth production – a tale of love and learning about a foreign culture, visually beautiful and simple-hearted, but able to surprise with unconventional plot plays. The visual layer is inspired by Russian painting, primarily the works of Viktor Vasnetsov. To help with the fight scenes, sportsmen practicing the Russian martial art called sambo were hired. When necessary, film is showy and brutal, as during a naval skirmish between Norwegians and Danes. But when it’s essential, the atmosphere changes to intimate and idyllic.

Trees Grow on the Stones Too cannot compare to Stanislav Rostotskiy’s previous masterpieces (The Dawns Here Are Quiet, 1972; White Bim Black Ear, 1977), but it’s another successful film by this director. Certainly, co-financing from the Norwegians helped, resulting in a fuller picture of the old era, while successfully competing for financial benefits (eventually the film was a hit, but unfortunately didn’t live to see a sequel).

Shadow of the Raven (1988), dir. by Hrafn Gunnlaugsson

Among Icelandic filmmakers, Hrafn Gunnlaugsson made the greatest contribution to the genre of medieval adventure stories. He made three films that are part of a variety of entertainment cinema popular mainly in the US and Italy. The first of these pictures is internationally titled When the Raven Flies (1984), more on the last part of the trilogy – The White Viking (1991) – later in the text, and now a few words about the middle film of the series, known internationally as Shadow of the Raven (1988).

The plot is taken from the Celtic legend of Tristan and Isolde, but also from Scandinavian tales of blood feuds between clans. The thing takes place in 1077, when Iceland was already heavily Christianized, but the old customs were still alive. The protagonist is a young traveler Trausti (Reine Brynolfsson), who studied theology in Norway and, although he has pagan ancestors, is already largely imbued with the Christian faith. When he returns to his native Iceland, he becomes an unwitting participant in a quarrel over a stranded whale that is a real treasure for surviving the harsh winter. As tribesmen and enemies are gripped by rage, hatred and a lust for revenge, he thinks in terms of Christian forgiveness and love. Perfect in this context is the scene in which Trausti plunges a Viking knife into the ground as a sign of peace, and behind his back the tribesman Grim (Helgi Skúlason) throws his knife, killing his neighbor and incurring the wrath of his daughter Isolde (Tinna Gunnlaugsdóttir, the director’s sister).

That’s not all the important elements of the plot, because when the bishop (Sune Mangs) enters the village with his son Hjörleifur (Egill Ólafsson), the plot gets even more complicated and another conflict is created. What we have here is a thrilling, dynamic performance that holds you in suspense and draws you in with its frighteningly cold and bleak atmosphere. The aura created around the characters heralds the lack of hope for a better tomorrow. The middle, somewhat calmer act is followed by a squalid and unforgiving final chapter, where the prayerful formula Kyrie eleison is merely an act of desperation, not a true profession of faith, for the world has been overshadowed by the shadow of the infernal raven – a symbol of war and death – and no God will open the gates to paradise for man.

The White Viking (1991), dir. by Hrafn Gunnlaugsson

Mankind has developed many weapons, but the sharpest of them is a certain book called the Scriptures. Christianization proved more effective than the Vikings in conquering the world, and Odin eventually had to succumb to the Christian God. The White Viking is set during the declining reign of Norwegian King Olaf Tryggvason (between 999-1000), who sought to eliminate pagan temples and replace them with Catholic churches. The primary source of inspiration for the screenwriters was Ari Thorgilsson’s The Book of Icelanders (Íslendingabók), written in the 12th century.

The main characters in the film are Askur (Gotti Sigurdarson) and Embla (Maria Bonnevie) – names from Norse mythology denoting the first humans created by the gods, and therefore the pagan counterparts of Adam and Eve. This alone shows how the two religions are similar, as each is based on the same principles. Embla is the daughter of the Norwegian jarl Godbrandur, while Askur’s father is the lawspeaker of the Icelandic Althing, Thorgeir Thorkelsson (an authentic character played by Helgi Skúlason). In the opening sequence, they participate in a nuptial ritual along the lines of traditional Nordic ceremonies, but the ceremony is interrupted by supporters of Christianity led by King Olaf (Egill Ólafsson). Askur is forced to convince his fellow Icelanders to embrace the Christian faith. To make sure he takes the task seriously, Olaf takes Embla hostage.

The film exists in three editions. The most popular is the two-hour producer version with Askur as the main character. In the second edition, the film takes the form of a four-part mini-series with authentic scenes of animal sacrifice. Meanwhile, the third release, made available in 2007, is a director’s version titled Embla. It’s shorter than the original one, because the director removed many scenes with Askur in order to better show the character of the female protagonist (this treatment was probably not only a result of the director’s vision, but also the fact that Maria Bonnevie, for the first time on the screen, performed much better than her film partner).

The Northman (2022), dir. by Robert Eggers

When the protagonist catches a spear in flight and throws it towards the enemy, and then, together with a small squad of warriors, with frenzied fury written on his face, pushes through the walls of the city – and this is realized as a mastershot – it’s already clear that we’re dealing with a film whose director knows exactly what he’s doing. Robert Eggers based the script for his third feature-length film on the Danish legend of Prince Amleth, son of Horvendill, lord of the Jutes. The legend is best known from the accounts of Saxo Grammaticus (Deeds of the Danes / Gesta Danorum, 12th/13th century), and today is associated with William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The film begins with King Horvendill (Ethan Hawke) returning to his family nest, where his wife Gudrún (Nicole Kidman) and 12-year-old son Amleth (Oscar Novak) are waiting longingly for him. The battle-hardened ruler wants to pass on his inheritance to his son, but shortly after the initiation ritual he is killed by Fjölnir (Claes Bang), his brother. Witnessing the murder is Amleth, whose purpose in life from now on is to avenge his father.

Eggers interprets the motif of revenge as a rejection of humanity and an entrance into the soul of a wild animal. The protagonist transforms from an innocent child into a berserker named Björn-úlfur (Alexander Skarsgård), a bear-wolf in whose heart smoulders a never-quenching flame. The result of this heat is an unbridled madness that makes the main character an anti-hero figure – someone who has become a beast more cruel than the one who contributed to his harm. But even the beast has human reflexes, and they are most evident in his relationship with the Slavic slave Olga (Anya Taylor-Joy). The life of the northman resembles the barren, volcanic soil of Iceland – no beautiful fruits flourish, only bitter, hallucinogenic, sometimes even poisonous weeds.

British archaeologist Neil Price, an expert on the Viking Age, was a consultant on the film, but the director, together with Icelandic screenwriter Sjón Sigurdsson (Dancer in the Dark, Lamb), treated with respect not only the history of Iceland at the turn of the 9th and 10th centuries, but also its mythology and animal symbols (ravens, bears, wolves). In addition to the historical realities – most believable in the visuals, which are full of dirt, blood, extreme violence, surreal rituals and Iceland’s natural settings – viewers get a large dose of mysticism and psychedelia. The lead role is based on physicality, but the challenge for Skarsgård was not easy, as it required bringing out his animal nature. Robert Eggers has prepared another successful film feast that will be remembered for a long time. And while the production in question is be among my favorite pictures of the year, I place it lower than Hrafn Gunnlaugsson’s The Raven Trilogy in the category of Nordic stories.