WAR MOVIES you don’t know you should

Creating ranking like this is always a challenging task. After all, as the author, I write in a subjective manner, and tastes vary. Nonetheless, I endeavored to recommend films to movie enthusiasts that don’t often appear in such lists but are definitely worth attention. Especially since many of them are gems that often surpass artistically or visually those ‘classic’ or most commonly mentioned productions. Will I be able to intrigue you to explore some of them? I hope so, as I believe that each of the films listed below is of the highest cinematic quality.

ATTENTION: I would like to address comments right away. From my perspective, films that “only” take place during times of armed conflicts – not just depicting battles and military clashes – also belong to the broadly understood genre of war cinema. And often, in a much more poignant way, they depict the horrors of war – even from the perspective of observers of these events.

Ivan's Childhood (1962)

In 1962, one of the most prominent Russian film directors, Andrei Tarkovsky, made his debut with his first feature film titled Ivan’s Childhood. The talented young actor Nikolai Burlayev took on the lead role. The film is set during World War II and follows the story of a twelve-year-old orphan boy named Ivan. As Soviet forces battle the German troops, Ivan operates as a scout-partisan. Numerous flashbacks reveal that the boy’s parents were killed by the Germans.

Captured by Soviet soldiers, Ivan is interrogated by Lieutenant Galtsev (Yevgeny Zharikov). It’s in this instance that we first encounter the war-marked face of the boy. Despite his young age, he possesses a strong character, doesn’t allow himself to be controlled, and exudes arrogance and self-assuredness. He doesn’t ask questions; he sets demands. He is an adult, an experienced soldier, wrapped in the skin of a twelve-year-old. His charisma is shocking, even to adult soldiers – he stands before them, a fragile, unassuming blond boy. His posture and angelic face strongly contrast with his demeanor and intentions. Yet, there’s a certain kind of arrogance and fury within this seemingly innocent child. He issues orders. Times of carefree happiness are only revealed to us in Ivan’s dreams. Tarkovsky, after all, loves contrasts. Isn’t the greatest contrast that of a child and war itself? Blinded by hatred, fueled by vengeance, and determined, Ivan sets his goal on fighting at the frontlines.

Let’s pause for a moment on these mentioned contrasts. Tarkovsky divides the film into two realms – strikingly different – the realm of reality (war) and the realm of dreams (memories). In the former, Ivan’s face seldom displays a smile, except for when he meets Captain Kholin (Valentin Zubkov, although this role was originally intended for Vladimir Vysotsky). The tragedy that befalls him forces him to confront problems that a child should never have to face. But despite the charisma that Ivan displays, even though he claims to be “his own master,” there’s still a trace of the little boy within him. He can lose his strength and cry. He doesn’t handle recurring nightmares and visions well, yet with such trauma, even the most experienced adult might struggle.

Despite many typical war scenes, Tarkovsky’s intention was primarily to show the consequences of war. It’s not about death or destruction (although the film has those elements), but rather about the destruction of the human psyche. The director himself explains that by juxtaposing childhood and war, he wanted to express his deep hatred for it.

The film also features symbols close to Tarkovsky’s creative style, such as water, which became a recognizable element in his later works, as well as references to Christianity. It’s no wonder that this film, based on Vladimir Bogomolov’s short story, won numerous awards, including the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1962. It also served as an inspiration for some of the greatest creators in world cinema, such as Kieślowski, Bergman, and Parajanov.

Tarkovsky’s film is surely known to most of you, and the above analysis might serve as a mere reminder. For those who have somehow not come across this masterpiece, I wholeheartedly recommend watching it, for films like these are scarcely made anymore.

Shooting Dogs (2005)

In 1994, as a result of a genocide committed by the Hutu people against the Tutsi people, 800,000 individuals lost their lives. Despite the enormity of this tragedy, it was one of the conflicts that went largely unnoticed by “white people.” As Michael Caton-Jones demonstrates in his film Shooting Dogs, racial divisions have immense significance in matters of war. And it all begins innocently – with the registration of the Tutsi population, referred to as “cockroaches” by the Hutu. But do such registrations not remind us of something? Does it not eerily resemble the stigmatization of Jews? As Caton-Jones proves, we haven’t learned a thing.

In Rwanda, the massacre begins. Thousands of people, including Tutsi children, are killed on the streets. Those who miraculously survive seek refuge in the school run by Father Christopher (John Hurt), where UN forces are stationed. Among these individuals are not only black Tutsi but also forty Europeans. According to the UN, the “white” people deserve decent conditions. As if the Tutsi were not the same human beings experiencing fear and sorrow. Even though armed Hutu quickly gather on the other side of the school gate, even though they commit killings right before the eyes of European soldiers, even though they’re just waiting for one false move to attack the sheltering Tutsi on the school grounds – the representatives of the UN, as they stress, have their hands tied. Their task is to merely monitor the situation, not establish order. A mockery? Yes, an obvious one, but as one conversation between a concerned teacher and an utterly emotionless journalist reveals, they are just “piles of black-skinned people.” And since they’re not “ours,” it’s hard to be concerned about them. Shooting Dogs, also known as Beyond the Gates, is a deeply disturbing film not only about the recent massacre but also about racism and the helplessness of the UN and other organizations that, in such situations, can (or want to) do very little.

Tae Guk Gi: The Brotherhood of War (2004)

It’s the year 1950. The war between North Korea and South Korea is ongoing. Due to a forced conscription, two brothers with opposing views on the war, Jin-tae (Dong-gun Jang) and Jin-seok (Won Bin), are drafted into the military. Before being drafted, Jin-tae worked as a hardworking shoemaker. He sacrificed to financially support his younger brother’s education. However, even in the military, their brotherly love remains strong. Jin-tae swears to protect his brother at any cost and does everything he can to ensure that his younger brother is sent home, even if it means sacrificing his own life. Yet, Jin-tae, who was previously against the war, begins to change over time and under the influence of the situation he finds himself in, leading to conflicts between the brothers.

Directed by Je-gyu Kang, the film doesn’t deviate much from well-known American war movies. In fact, it has something that sets it apart, namely the scale of cruelty and the spiral of hatred depicted without excessive sentimentality. Kang portrays war realistically. Blood flows in streams. There are suicides by gunshot to the head, resulting in views of pierced skulls and exposed brain matter; masses of murdered soldiers; amputations due to anti-personnel mine injuries; gruesome wounds feeding larvae. The director doesn’t try to beautify anything, hide or shield us from these brutal images we’d rather not see. Kang doesn’t spare the audience. On the screen, there’s death, pain, suffering, and fear. There’s also hunger and the struggle for sustenance. However, physical suffering isn’t the only aspect – Kang doesn’t forget to portray the condition of the war-weary human spirit. To be truthful, he shows us not only the crimes of the communist regime but also the brutality of his own people, such as the treatment of prisoners of war.

The film makes us realize that people react to war in various ways. Some soldiers had reconciled with death from the beginning. They didn’t even attempt to hope for survival and return to their families. Others, however, displayed a strong will to fight and a desire to survive at all costs. As one of them says, “I will kill even children to survive.” The concept of honor is also interpreted differently. For some, it’s an objective or even an honor to die, while others directly question whether it’s worth being slaughtered for a foolish idea of combat.

The film’s director also shows how war turns people into beasts. They become vindictive, deceitful, and cunning, exemplified by the scene where explosive charges are placed under the corpses of the massacred population. War pulls people into its whirlpool, transforming them beyond recognition, even if they initially wanted no part in it.

Another strong point of the film is its cast. Unfortunately, there’s a rather significant flaw, namely the music, which is so sentimental and biased that it’s hard not to sigh, not out of sorrow but irritation. But well, perfection is rarely achieved, and while the soundtrack is indeed poor, it doesn’t negate the film’s value.

The Chekist (1992)

“Execution, execution, execution…” – this emotionless verdict repeatedly falls from the lips of the Chekists. We are transported to the headquarters of the Cheka, the secret Soviet police established by Lenin after the Bolshevik Revolution, in the powerful film The Chekist directed by Aleksandr Rogozhkin. Although the accusations are often mockery and sometimes merely a name is enough, there’s no room for discussion or contemplation. The verdict is always the same – execution. Among those giving this order is the unscrupulous, emotionless, and conscienceless head of the regional Cheka, Andrey Srubov (Igor Sergeyev). It is he who issues condemning verdicts on all sorts of class enemies that, according to the Chekists’ belief, need to be eliminated. People accused of various pretextual offenses, held in the basements of the Cheka headquarters, are forced to undress. Nobody is concerned with shame here. There’s no time for that. Women and men go side by side, then they are lined up in rows facing the wall, and a shot is fired into the back of their heads. And so, one after another. The rows of the condemned seem endless, as the lines marked on the walls remind us. It might not be so terrifying if it weren’t for the awareness that Rogozhkin’s film tells of real events from the time of the Russian Civil War, when in the Soviet Union, all enemies of the system were treated without mercy (it’s worth noting the director’s courage as a Russian to confront this truth). All of this takes place in gray, blood-splattered corridors. The bodies are then hoisted up by ropes and loaded onto a truck. We see horrifying piles of naked bodies. It’s one massive death machine. As one of the characters says, it’s not a spectacle like public executions, where murder was committed in front of the entire people; here, everything happens quietly. In secret. And it lasts for a short moment. It’s a very simple principle: there was a person, and now there’s no person. Not even a trace of them.

But Rogozhkin’s film is not only a portrayal of the Chekists’ hypocrisy and the terrifying mass murder of thousands of people, including clergy, intellectuals, and Jews. The director also leaves room for contemplation. Amid the successive executions, we can listen to the conversations and reflections of the main character, Srubov. Asked whether he feels regret and fear because of the executed people, he firmly states that he doesn’t. But he’s not the only one devoid of a conscience. Informers also come to Srubov, for whom it never crosses their minds that their reports likely take someone’s life. Srubov’s attitude changes over time. In another dialogue, one of the executioners tells Srubov: “I’m a worker, and you’re an intellectual. You have philosophy, and I have hatred.” What is the meaning of human life to another human being? Or perhaps there isn’t one at all? After all, as it turns out, during the reading of the accusations, the Chekists don’t even listen to their content. Undoubtedly, the director addresses the topic of murdering in the name of a sick ideology and shows that this action has no trace of pathos.

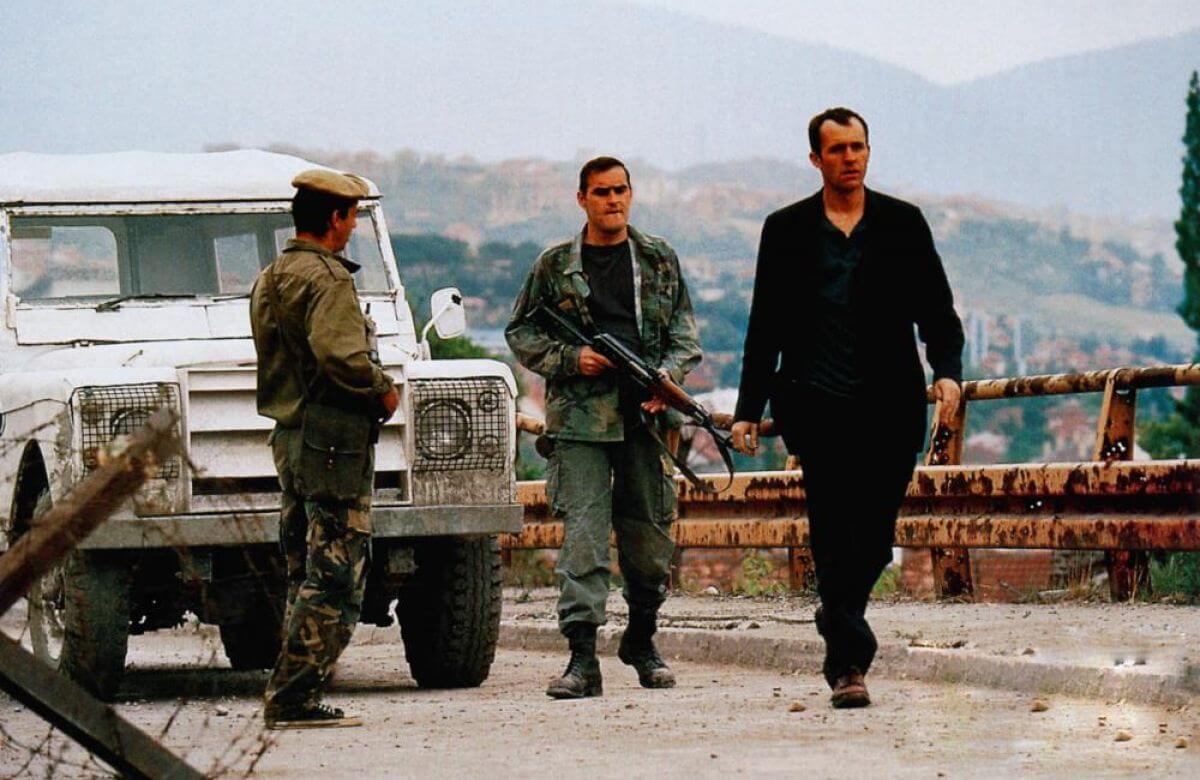

Welcome to Sarajevo (1997)

Another war film that deserves attention is the drama Welcome to Sarajevo directed by Michael Winterbottom, set in the besieged city of Sarajevo during the conflict with the Serbs. The director masterfully portrays human indifference. This time, it’s not about soldiers or those passing judgments, but about war correspondents working in Sarajevo. When they’re not filming shocking materials, they spend their time partying, having merry conversations, and drinking expensive alcohol. Right next door, the war rages on. People live in fear for their lives as snipers lurk at every corner. They don’t even have enough money for food. No one can feel safe anywhere. But for the journalists, it doesn’t matter. While they raise toasts, explosions can be heard outside, and people continue to die on the streets. To make matters worse, the shocking photos and materials they’re trying to obtain at any cost are not intended to help the city. As one can easily guess, it’s all about increasing viewership and advancing their careers. Politicians also show indifference, using ridiculous arguments. According to them, the situation in Sarajevo isn’t the worst compared to other countries. However, when asked to specify which countries they mean, they can’t provide an answer. They also claim that patience is needed. It’s easy to utter such empty words when you have security and everything needed for life. It’s easy to offer reassurances when you don’t have piles of dead bodies, wounded people screaming in pain, or terrified children crying nearby. The inaction of politicians and decision-makers is horrifying.

Thankfully, among the indifferent war correspondents, there’s one whose emotions haven’t been extinguished. Michael Henderson (Stephen Dillane) becomes involved in helping children from an orphanage. But to what extent will he be willing to go in this endeavor?

A significant asset of this drama is that the filmmakers incorporated real footage into the film. This approach gives events from that time a much more vivid resonance. We can’t shrug our shoulders and say, “it’s just fiction.”

Lastly, I’d like to mention the music. In scenes depicting the dead, the wounded, and the politicians who are eager to avoid responsibility and refuse to provide any assistance, you can hear the ironically used song “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” by Bobby McFerrin playing in the background. Kudos to the film’s creators.

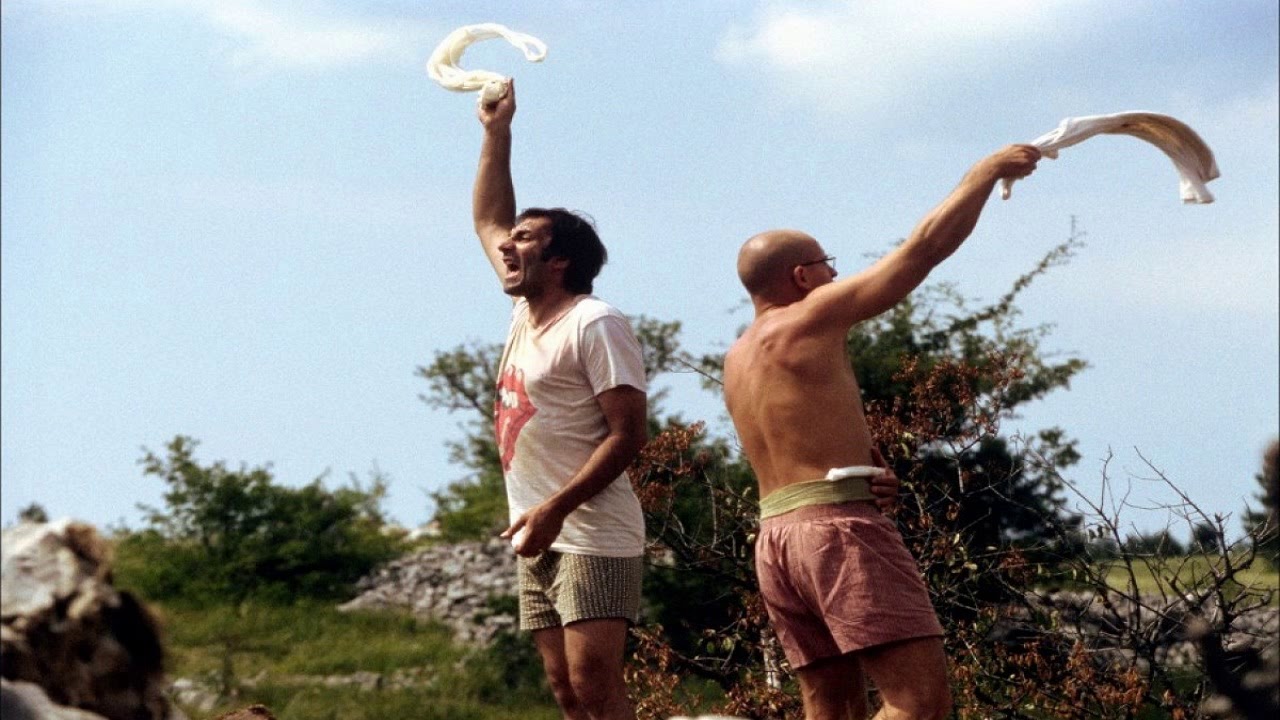

No Man's Land (2001)

Film No Man’s Land directed by Danis Tanović is also centered around the conflict between Serbs and Bosniaks. Due to a twist of fate, a wounded Bosniak soldier, Čiki (Branko Djurić), finds himself in a trench on the so-called no man’s land between Bosnian and Serbian territories. Two Serbian soldiers, including the inexperienced Nino (Rene Bitorajac), are sent to search that trench. They discover the body of a murdered soldier, Cera (Filip Šovagović), and decide to place a spring-loaded mine underneath the body. This type of mine explodes not when pressure is applied, but when it’s released. The Serbians hope that Bosnian soldiers will return for their comrade’s body, triggering the explosion when they move it. Until this point, the hidden Bosniak soldier emerges from his hiding spot, kills one of the enemy soldiers, and confronts the other, sparing his life. There’s a display of power between the two soldiers, with the upper hand going to whoever is armed. Although they initially blame each other, accusing each other, and argue about who started the war, despite their mutual reluctance that doesn’t seem like hatred, they soon realize they need to temporarily lay down their weapons and start cooperating to survive. However, they soon discover that they’re in a worse situation than they initially thought – the soldier lying on the mine is not dead, and the slightest movement can result in a tragic death for all three.

While Tanović’s film has numerous comedic elements, in my opinion, it is predominantly dramatic from start to finish. The trapped soldiers are observed by Serbian and Bosnian forces from both sides, with no inkling that there’s a mine in the trench. When they call for help (UN), we see a situation very similar to what we witnessed in the film Shooting Dogs – peacekeeping organizations merely observe and cannot actively engage. And although the film includes the line “one must not remain indifferent in the face of murder,” precisely that happens. Everyone who could help washes their hands of the situation and withdraws, regardless of the fact that three human lives are at stake. Similarly to Welcome to Sarajevo, grand words, promises, and justifications are uttered here, which ultimately lack substance and mean nothing. Tanović also criticizes the greed of journalists in his film. They show no concern for human lives or the tragedy of the three soldiers – only obtaining interesting material matters. A memorable scene is when a journalist asks her cameraman to zoom in on the face of the soldier lying on the mine, while the sappers are defusing it. Isn’t this a clear example of complete dehumanization? Tanović not only portrays the utter senselessness of war but also the heartlessness of people from various backgrounds and the need to only care about their own interests. I’ll reveal that the film remains tragic right until the end, and even if you smile a few times during the viewing, the ending will effectively wipe that smile off your face.

Corn Island (2014)

Corn Island directed by George Ovashvili also takes place on no man’s land. It’s the year 1992, during the war between Georgia and Abkhazia, seeking independence. An Abkhazian elder (Ilyas Salman) and his granddaughter (Mariam Buturishvili) settle on a small island that emerged in the early spring on the Inguri River. The island’s unusually fertile soil allows them to plant corn, the main source of food for the locals during the winter. Life on the island flows slowly. Its inhabitants hardly talk to each other, and their main focus is hard work. They build a wooden hut from scratch, and they plant corn from scratch. They are entirely dependent on nature, which can be cruel. But they have no other choice. Their island is situated between territories belonging to Georgia and Abkhazia. Boats continue to pass by, sometimes belonging to one side, sometimes to the other, yet neither the elder nor the girl seem to be affected by it. They have their own war. A war with nature, which is just as exhausting as armed conflicts.

One day, their life changes. A fugitive Georgian soldier seeks refuge on the island. Will the elder and the girl finally get involved in the conflict happening right next to them? Will they help the soldier, risking their own lives? Many of you might wonder why this film is ranked among war movies. After all, there are sounds of explosions and gunfire, two sides of a conflict, and a wounded soldier, but not much else. Mostly, it’s a film about survival. About how wind or rain can undo months of work. But is it only that? War doesn’t necessarily need to be shown directly to talk about it. It doesn’t need to be loud and extravagant, as Americans often do. It can be intimate and low-budget and still be just as captivating. Perhaps even more so? I guarantee that Ovashvili’s film, enriched with extraordinary cinematography, will evoke a lot of emotions in you.

City of Life and Death (2009)

“Chinese also have their own Spielberg. And his name is Chuan Lu. Did you enjoy directorial achievements like Saving Private Ryan, Dunkirk, or 1917? This masterfully crafted war film was made with such grandeur that it’s hard to imagine it didn’t come from the hands of Nolan or other specialists in spectacular cinema. Moreover, it’s an incredibly poignant and almost documentary-like depiction.

With the precision (and honesty, which was a huge surprise for me) of a good documentarian, Lu shows us arguably the most disgraceful part of Japanese history – the so-called Nanking Massacre, also known as the ‘Rape of Nanking’.

In 1937, Nanking was the capital of China, and the Imperial Japanese Army marched into it, committing unimaginable acts of genocide, rape, and plunder for the next six weeks – mostly targeting civilians, including women and children (according to researchers, not a single unraped woman remained in the city) – which claimed over 300,000 human lives.

Of course, at the heart of the story is the bleeding, burning city, but we observe it through the eyes of several characters: a Nazi official named John Rabe (John Paisley), who (which might sound somewhat abstract) saved thousands of Chinese in a safety zone he organized, a Japanese soldier torn by doubts and horrified by the cruelty of his companions (Hideo Nakaizumi), and a Chinese guerrilla fighter (Ye Liu), desperately struggling for survival amid the city’s ruins.

It’s a terrifying spectacle, but undoubtedly worth the attention of every war cinema enthusiast, if only for the mind-boggling ‘victory dance’ scene of the Japanese troops amidst the ruins and bodies of Nanking’s inhabitants. A very powerful piece.

Fires on the Plain (1959)

And since we’re talking about powerful productions… Heat, humidity, hunger, indifference, an endless journey – and pervasive death. Death that is almost trivial, to which the protagonists of Fires on the Plain react almost apathetically. The film directed by Kon Ichikawa, based on the famous autobiographical book by Shōhei Ōoka, is a cold (though bathed in the deep heat of the sun) study of the disintegration of humanity, the decline of morality, and the slowly and gradually emerging – albeit inevitably – madness.

Private Tamura (Eiji Funakoshi) is expelled from his unit fighting on the Philippine Islands due to pneumonia. After leaving the hospital, he traverses the island in search of his comrades. Devoid of supplies, ravaged by illness and war itself, he has little chance of survival. However, it quickly becomes apparent that hunger is worse than death…

Even though the film is over 60 years old, it hasn’t lost any of its impact and uncompromising nature – and its anti-war message is still relevant today. The slow pace and the almost lack of spectacular action scenes only enhance the sense of hopelessness, emptiness, and fear.

An absolute classic of world cinema. It’s hard to find another film that portrays the horror and senselessness of war in such a suggestive way.

BONUS: Everything Is Illuminated (2005)

A film not necessarily strictly war-related, but definitely worth including on this list. An excellent and unconventional directorial debut by the popular supporting actor and TV series star Liev Schreiber, this film isn’t a typical war movie, though the events associated with war are crucial to the fates of all the characters. Here, Jonathan, a collector of family memorabilia (one of Elijah Wood’s best roles), an American of Jewish-Ukrainian descent, embarks on a sentimental journey to Eastern Europe to find the mysterious Augustine – the woman who saved his (now deceased) beloved grandfather from a Nazi pogrom in Ukraine. He has few clues, just a fragment of information from his grandmother, an old photograph, and a necklace – a cricket embedded in amber. Joining him on this peculiar journey are Ukrainians from Odessa: translator Alex (played by the brilliant Eugene Hutz, the frontman of the famous gypsy punk band Gogol Bordello) and his grandfather, a blind (as Alex reassures Jonathan, “only he thinks that”) driver portrayed by Boris Leskin. And of course, the adorable Sammy Davis Junior Junior, the designated “official seeing-eye bitch” of their driver. This will be a bittersweet journey full of funny situations (Jonathan is a vegetarian and a compulsive introvert, which will cause him a lot of trouble during the trip) and joy, but also pain and melancholy. Moreover, many family secrets of the expedition’s participants are hidden behind it all. Illumination will reach everyone, each in their own way.

Liev Schreiber’s film is a moving portrait of breaking down intercultural barriers, accepting oneself and others, and also about the importance of the past and memories of it. And in the background, a poignant history that dates back to World War II events. Did I mention the fantastic folk-rock music?