Jack Torrance from THE SHINING. The Truth Behind the Psycho

… in almost luxurious conditions, surrounded by beautiful scenery, and with a guaranteed salary might at first glance seem truly appealing. An excellent opportunity to spiritually cleanse oneself, reboot the internal system, reevaluate a few things, and tackle plans postponed for later. Jack Torrance seems to view it exactly that way.

Rest, solitude, very specific and essentially mechanical duties, freedom, and disconnection from the judgmental and evaluative gazes of others are precisely what he needs to rediscover the forgotten writer within himself, cement his family, and atone for the mistakes made by the old Jack, the one who drank, couldn’t control himself, and drunkenly dislocated his son’s arm. The new Jack Torrance is a responsible family provider, impeccably mannered, uttering smooth sentences, and promising himself he won’t stand out. The Shining

But even at the outset, we see that this image has a few cracks. Jack isn’t starting from a good position. He isn’t relaxed, doesn’t feel confident; instead, he appears tense, nervously rubbing his pant leg, smiling dryly. During the car scene, as the Torrances head to their destination, it is clear they are far from a united, close-knit family. Jack is irritated, struggling to suppress impatience, collecting himself before speaking to avoid snapping. Wendy is unsure of how to behave around her husband, fearful of accidentally triggering his spring of aggression. Danny announces he knows everything about cannibalism—after all, he saw it on TV. See, everything’s fine, he saw it on TV, quips Jack, and one can almost hear the unspoken sentence because you let him watch it. Jack and Wendy’s nervousness is also evident later during the hotel tour: she chatters incessantly, displaying childish enthusiasm in the hope that no one notices her terror at the prospect of half a year of isolation. He pulls faces meant to convey absolute delight at this fantastic hotel gig. And Danny, well, Danny has bad premonitions, voiced aloud by the discontented Tony.

Time passes, and while Danny on his bike adventures repeatedly encounters the ghosts of past Christmases, and Wendy desperately battles boredom and loneliness, Jack slowly edges toward a breakdown. He begins to exhibit the first concerning symptoms. Racing thoughts (so many ideas, but none good). Insomnia, an inability to rest, anxiety (I have so much to do). If he does sleep—vivid, intense nightmares. Difficulty concentrating, with the slightest thing disrupting his rhythm. Irritation and irritability. Jack has just woken up on the floor, in Wendy’s arms, crying over a terrible dream. Danny enters the room, deeply shocked, sucking his finger and bearing marks of strangulation on his neck. Assuming her husband has once again lost control and tried to harm their child, Wendy grabs Danny and flees, while Jack unsteadily makes his way to the ballroom to sit at the empty bar. Let’s leave him there for a moment.

As for whether there truly is a syndrome known as cabin fever—and more specifically, whether it should be classified as a distinct medical condition—debate continues. The syndrome manifests as restlessness, impatience, a sense of hopelessness bordering on depression, persistent drowsiness, morning fatigue, reduced stress resilience, erratic appetite swings that can result in weight fluctuations, and so on—all as a consequence of prolonged isolation in an environment cut off from human contact. There’s also a theory that being separated from stimuli in the form of people interpreting and reacting to our actions, serving as a mirror for us, we gradually struggle to determine which of our behaviors are socially acceptable. Another school of thought argues that cabin fever is a byproduct of claustrophobia or seasonal affective disorder, fueled by isolation and confinement. It doesn’t inherently spawn extreme aggression (at least, this hasn’t been conclusively observed), though it may be a factor exacerbating the difficulties faced by individuals with other types of disorders.

After several months in the Overlook Hotel, Jack is exposed to both the dangers of isolation syndrome and the effects of alcohol withdrawal. Much suggests he suffers from undiagnosed bipolar disorder, which, like many unaware sufferers, he attempted to self-manage through alcohol abuse. Cut off from both substances and the world, Jack gradually enters a state of acute mania, within which he experiences severe psychosis. The first signs of mania can be seen in the scene where Jack harshly scolds his wife for disrupting his concentration. Then the symptoms multiply, as I’ve already mentioned: irritability, insomnia, racing thoughts, motor compulsions… and so forth.

While delusions typical of schizophrenia are often entrenched, long-lasting, and usually negative, the delusions experienced during manic-phase psychosis emerge suddenly, intensely, and may reflect the fulfillment of hidden desires, ego gratification, a sense of camaraderie, or the satisfaction of sexual needs. And this is exactly how Jack’s delusions and hallucinations manifest—a whole bar just for him, a bottle of bourbon, and the empathetic, all-understanding Lloyd, to whom he can confess without fear. Even the encounter in the infamous Room 237 initially takes on a purely erotic dimension before descending into horror—let’s add that Jack retains enough control to keep the encounter a secret from Wendy. Colors in manic hallucinations are often saturated, vivid, highly intense, and the entire construct is multi-elemental and specific, like a film set with actors, costumes, and makeup.

Not every individual with bipolar disorder experiences severe manic phases, nor does every severe manic phase involve psychosis—but Jack received the full package. And the circumstances were highly conducive. As I mentioned earlier, the very start of the adventure at the Overlook was burdensome for Jack. His marriage isn’t doing well, and apparently hasn’t been for a long time. Wendy is, for her husband, the embodiment of failure, a bitter reminder of squandered opportunities and a lost writing career. He blames her for his shortcomings and failures, claiming she ruined his life and tormented him with guilt.

The more time passes, the angrier he becomes with her, as Wendy doesn’t share his fascination with the hotel, doesn’t understand how important it is for him to be there, and even turns their son against him. All his frustration, all his anger, focuses on her—consciously, though less consciously he also blames Danny. The very existence of a family and the need to support it distracted him from his calling as a writer and prevented him from fulfilling himself. At the Overlook, Jack feels free from pressure for the first time in a long time and builds a comfort zone so precious to him that he wants to protect it at all costs. The spiral of madness tightens, fueled by rage and aggression.

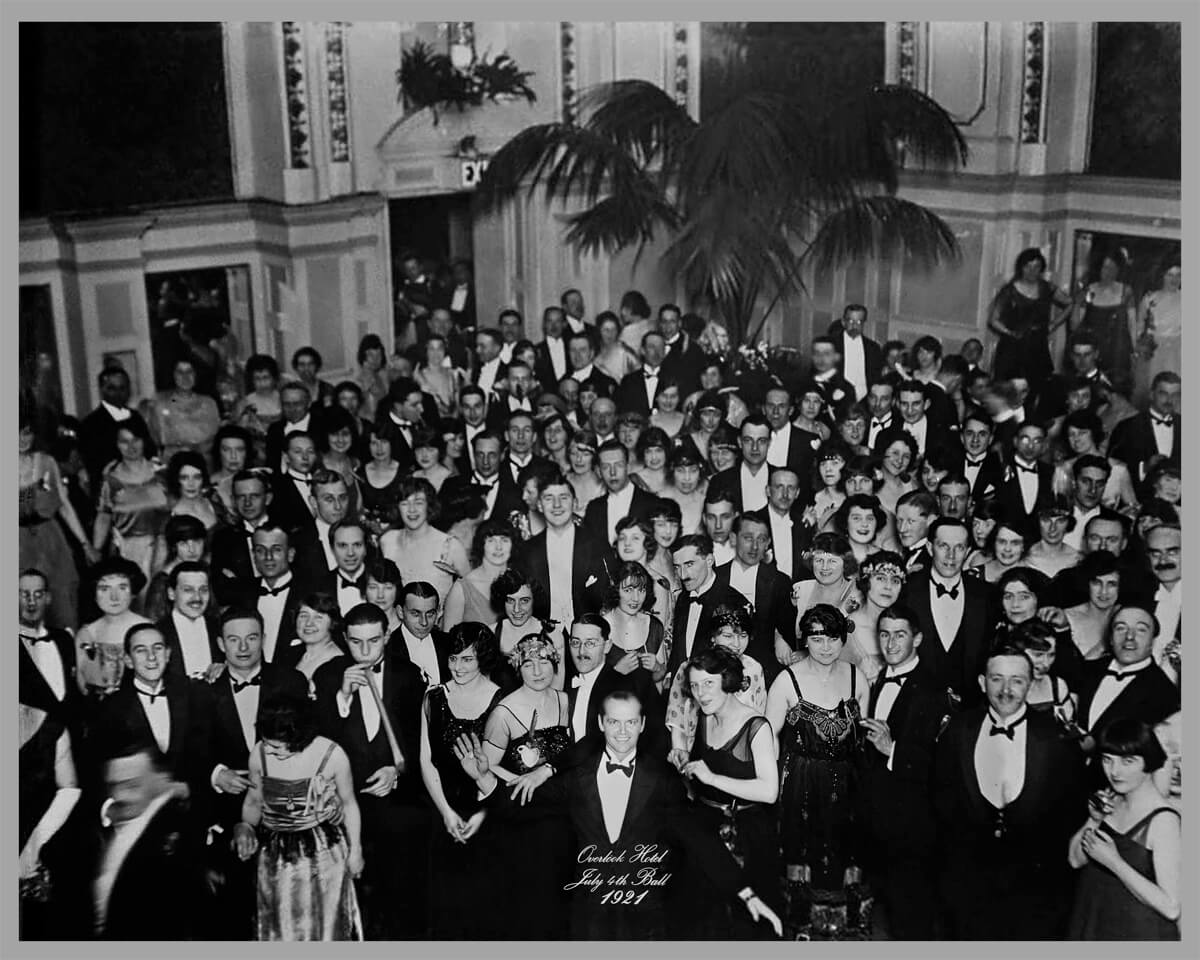

But wait a minute—someone might say at this point. Does this mean that the hotel itself has no role here, that nothing sinister is happening, and it’s all just a projection of Jack’s disturbed mind? No, one doesn’t exclude the other; in fact, one fuels the other. The hotel’s history reflects a vicious cycle of violence embodied by the caretaker figure—as suggested by the 1921 photo in the final scene, Jack is its latest incarnation. A cycle of violence difficult to escape, as the archetype of the caretaker has existed forever. Jack, given his specific disorders, is the ideal vessel for this.

Violence is no stranger to him, perhaps even in a harsher form than we actually see on screen—after all, he harmed Danny while drunk, and this might not be the only instance of aggression he directed toward his family. Wendy, telling the doctor about her son’s accident, adopts the classic stance of a justifying wife: it was an accident, these things happen, poorly estimated force… and so on. And Danny has Tony, his invisible friend, who is both an expression of shining and his protector, stronger and more aware. To the extent that, following trauma, Danny withdraws deep within himself, and Tony takes over, telling Wendy that Danny isn’t here, Mrs. Torrance. A similar trauma must have caused Tony to appear in the first place.

Some interpretations even find elements suggesting sexual abuse of Danny by Jack, though to me these are unconvincing. However, pressure, severity, and criticism are clearly present, to the extent that the boy doesn’t feel comfortable around his father and is even afraid of him. Advocates of rational explanations for the events at the Overlook Hotel even suggest that it was Danny—or rather Tony—who released Jack from the pantry, seeking an ultimate confrontation (in the spirit of redrum, of course). And Wendy’s visions? Well, a fatigued mind, extreme terror, or perhaps a case of folie à deux. It’s a defensible theory, but Kubrick’s brilliant concept loses much of its impact this way. If we accept elements beyond rationality while retaining the paranoia that besieges Jack, the story of The Shining becomes more symbolic and universal.

However, possession of Torrance isn’t the cause of his breakdown but its consequence. The seed fell on fertile ground.

Hotels with a long tradition inevitably become witnesses to brutality, betrayal, despair, breakdowns, loneliness, desires for revenge, and other equally intense emotions over time. Emotions so powerful that they leave an echo, an imprint in the fabric of time. One of the most famous examples is the Cecil Hotel in Los Angeles, now renamed Stay on Main, built in 1924 as a haven for wealthy businessmen. However, during the Depression, the street it was built on transformed within a few years from a tidy Main Street into a hub for the homeless, maintaining its grim reputation to this day. Within the hotel itself, numerous suicides and at least three murders occurred. Moreover, two infamous serial killers—Richard Ramirez in 1985 and Jack Unterweger in 1991—stayed there for extended periods. The hotel, which inspired the fifth season of American Horror Story, made headlines again due to the tragedy of Elisa Lam, a 21-year-old Canadian student whose naked body was found in the rooftop water tank after guests complained about low water pressure and a strange taste. Some time later, hotel surveillance footage of Elisa behaving strangely in the elevator leaked online.

Though it was later revealed that the video had been partially manipulated to emphasize her strangeness, and Elisa suffered from, surprise, bipolar disorder, having neglected her medication for some time, likely resulting in a manic episode with paranoia and her tragic but accidental drowning—the internet is still rife with speculation about supernatural forces and alleged possession. Such is the power of the legend of an old hotel. The same phenomenon occurred with Amityville following the murder of the DeFeo family. Under the right conditions, urban legend and facts quickly intertwine, making it hard to separate one from the other.

The same goes for the symbolism of the Overlook Hotel—the second main character of The Shining alongside Jack—which year after year, for decades, patiently absorbed every conceivable negative emotion. Their echoes are visible to both Danny and Wendy. Over time, this isolated mountain hotel became a true monument to depravity, violence, and madness, becoming a labyrinth with no exit for someone in Jack’s situation.