Everything You Need to Know About Polish Cinema of Moral Anxiety

During this time, amidst growing social discontent and increasing opposition to the communist regime, as well as a slight degree of creative freedom, a movement known as the Cinema of Moral Anxiety emerged. Filmmakers opposed the propaganda of the political system, exposing its various corruptions, manipulations, falsehoods, and its destructive impact on individuals and society as a whole.

The central element of the works in this movement typically features a relatively young protagonist who confronts the mechanisms governing the reality of communist Poland. Their actions and principles clash with the presented realities, forcing them to choose one of two paths. The first path involves independently facing conformity, pressures, and increasing obstacles to achieve their goal or simply maintain their moral integrity. In the second scenario, the protagonist becomes a scoundrel who, at any cost, seeks to gain benefits solely for themselves, only to eventually be unmasked. Regardless of the character chosen by the creators, the world they depict is always gray, sad, and extremely demanding, especially for idealists. The Cinema of Moral Anxiety emphasizes realism and contemporaneity, with a clearly defined authorial stance. These characteristics garnered the movement its critics, who primarily accused the films of having a black-and-white view of the world and technical weaknesses. It should be openly stated that they did not enjoy particular popularity among the general audience. Nonetheless, the Cinema of Moral Anxiety produced many excellent, even outstanding works that significantly influenced Polish cinematography.

We present a selection of fifteen of the most important works of this movement, whose main themes were issues of freedom and liberty. As is often the case with artistic movements, its boundaries are very fluid, and some films are considered part of the core canon, while others are on the periphery. In this article, we focus on the most significant representatives of the Cinema of Moral Anxiety, as well as a few examples from the periphery, without exhausting this interesting, much broader topic.

Man of Marble (1976), dir. Andrzej Wajda

One of the most important films in all of Polish cinema, which in a way gave a signal to other filmmakers (usually younger than Wajda himself) to go full steam ahead. Man of Marble contains all the constitutive features of the movement. The main character is Agnieszka (played by debuting actress Krystyna Janda), a novice director who wants to make a film about a former model worker, Mateusz Birkut (Jerzy Radziwiłowicz). The great career of the builder of socialism ended unexpectedly many years earlier, and he has since disappeared from public view. Agnieszka begins an investigation to find out what happened to Birkut. Along the way, she encounters many difficulties from people associated with the hero of her film. Wajda’s film depicts the struggle of an individual against totalitarianism—she is almost powerless against it, seemingly doomed to failure. However, Agnieszka does not necessarily have to repeat Birkut’s fate. The conclusion of Man of Marble is an appeal for courage and perseverance despite mounting difficulties. On a meta-film level, Wajda’s work is also a story about the challenges of making a film (and art in general) in times of pervasive pressure and control.

Camouflage (1976), dir. Krzysztof Zanussi

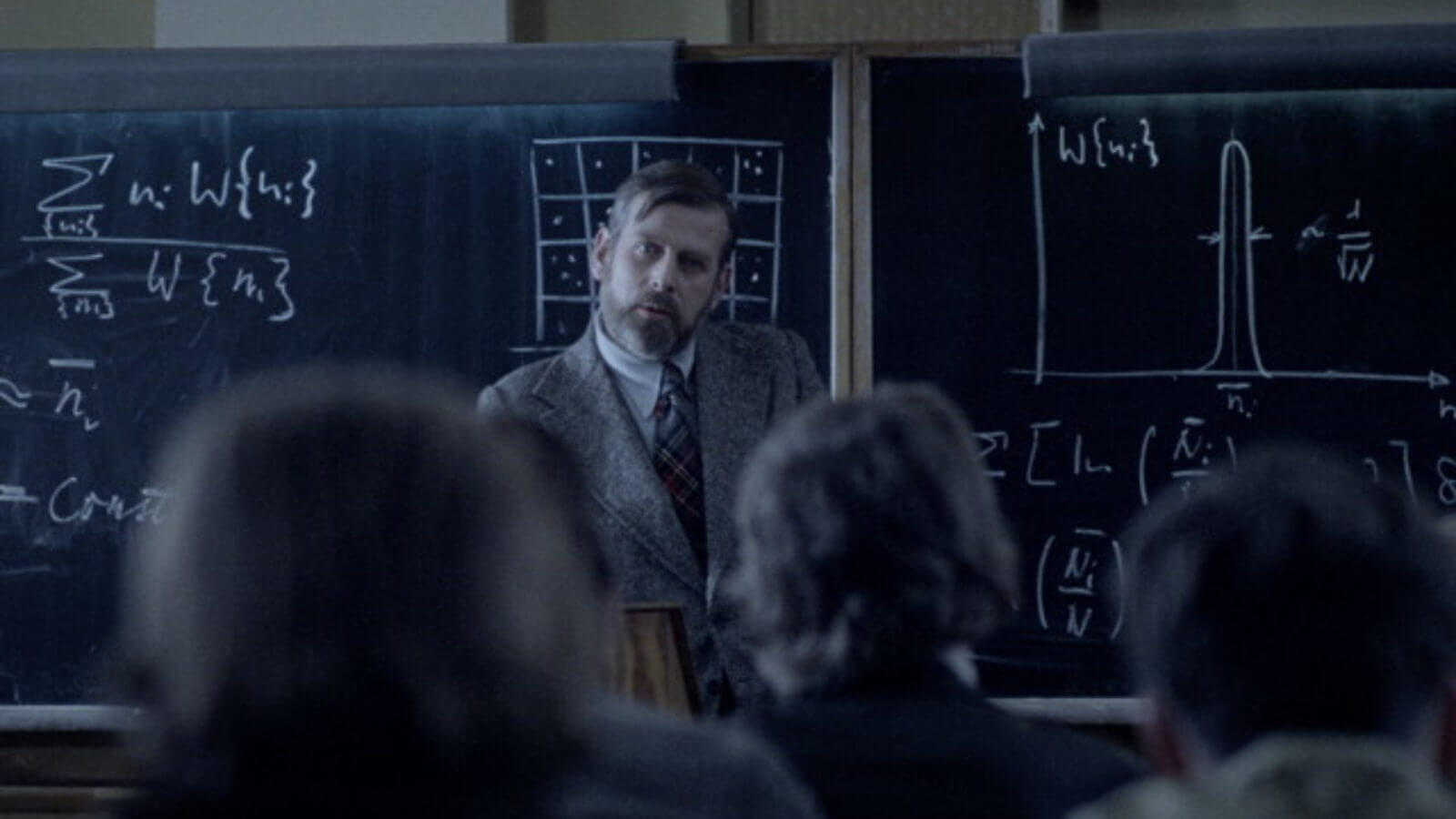

A common practice among filmmakers of this movement was constructing a plot based on the confrontation of two attitudes. This usually took the form of a morality play, a kind of struggle for the soul of a positive protagonist by a corrupt antagonist. This is how Camouflage by Krzysztof Zanussi is presented. Here, evil is represented by docent Szelestowski (Zbigniew Zapasiewicz), the supervisor of a summer language camp for university teachers and students. Under his wing is Jarosław (Piotr Garlicki), a young graduate. After a series of conversations with his older colleague, the idealist becomes convinced that the academic environment is a bunch of cheaters and conformists operating primarily through connections and acquaintances. Camouflage becomes most fascinating during the numerous dialogues between the graduate and his nemesis, the docent. There, long exchanges of arguments take place, where the young man is under constant pressure and it seems that his reasons stand no chance against the demonic careerist devoid of a moral backbone. Jarosław does not give in, although Zanussi shows that taking the path of convenience and servility is very easy and tempting. This, however, is only a mask hiding the inner emptiness of a degenerate clique.

The Calm (1976), dir. Krzysztof Kieślowski

The titular peace is the greatest dream of Antoni Gralak (Jerzy Stuhr). After being released from prison, he desires only stability—a roof over his head, a job, and eventually his own place and a family. His modest expectations slowly begin to materialize, and Antoni is on the right track to achieving a sense of happiness. However, it is not as simple as it seems, as everyday life brings about friction that can quickly lead to disaster. The greatest merit of The Calm is its avoidance of overt moralizing and political references. The main character does not fight for ideals detached from reality, nor is he a typical sycophant. He only seeks a peaceful existence, led at his own pace, without bothering anyone. Neutrality, as Kieślowski seems to say, also comes at a price, and life always requires difficult choices and taking a clear stance. Otherwise, one may risk alienating everyone and ending up without any support.

Index (1977), dir. Janusz Kijowski

The central figure of Janusz Kijowski’s film is a staunch rebel, Józef (Krzysztof Zaleski). When one of his friends is mysteriously expelled from the student list, the main character demands an explanation. Józef is very impulsive and usually cannot hold his tongue, so it doesn’t take long before he is arrested by the police, expelled from his studies, and evicted from his apartment. The young man tries to make ends meet, but his stubbornness, unwillingness to compromise, and unwavering pursuit of his plans are not allies for a student in Poland after 1968. Index at times loses its dynamism, but such is Józef’s life – gray, devoid of prospects, and unhappy. One might say that the protagonist is his own worst enemy, often bringing misfortune upon himself. Nevertheless, Kijowski portrays a character determined to fulfill his dreams and not settle for half-measures or mediocrity. Moreover, everyone around him is trying to settle down, find stability, and lead a simple and safe life. For Józef, however, honor and the sense that he will never have trouble looking himself in the mirror are most important.

A Room with a View on the Sea (1977), dir. Janusz Zaorski

Janusz Zaorski also presents a conflict of attitudes in A Room with a View on the Sea. The 1977 film begins when a mysterious young man, later named Michał, enters the top floor of a high-rise building in Gdańsk and threatens to commit suicide. Two psychiatrists engage in conversations with the young man. The first, Professor Leszczyński (Gustaw Holoubek), is an experienced therapist in retirement, while the second, Dr. Kucharski (Piotr Fronczewski), is a young, confident lecturer. At a certain point, tension arises between the two scientists. Leszczyński wants to reach out to the boy and convince him to make the decision to come down on his own. Kucharski, on the other hand, tries to lure Michał back inside using trickery, bribery, and even pharmacological means. The dominant theme in Zaorski’s film is the issue of freedom—the professor does not want to impose his will on the potential suicide or force him to live. It is up to Michał to decide whether to jump. The director shows in A Room… not only the difference between psychiatric practice and theory tested by life but also freedom itself, which was limited during communist times and the external pressure forcing individuals to act against their will.

Top Dog (1977), dir. Feliks Falk

The protagonist of Feliks Falk’s film is perhaps the most famous example of a repulsive, dishonest careerist in Polish cinema. He is Lutek Danielak (Jerzy Stuhr), the titular master of ceremonies. He leads minor events until one day he learns that a grand ball will be held to celebrate the opening of a new hotel. Danielak wants to host this event at any cost, but to do so, he must eliminate the competition. These are not just ordinary rivals, but colleagues from work, including a friend of Lutek’s. This fact does not deter him. Danielak begins to look for dirt on his colleagues, send anonymous letters, cheat, and even sells his own girlfriend for a car voucher. The protagonist evokes clear disgust in the viewer, but also a spark of pity—in pursuit of success, he loses love, friendship, and respect, perhaps even for himself. Much of Top Dog’s success can be attributed to Jerzy Stuhr, whose character can be meek, polite, and obliging, only to turn into a despicable schemer and extreme egoist in the next moment.

Provincial Actors (1978), dir. Agnieszka Holland

Disillusioned idealism also appears in Provincial Actors. In Agnieszka Holland’s film, the main character is Krzysztof (Tadeusz Huk), a theater actor. He is set to perform in a play directed by a debuting director but disagrees with the director’s vision. The young creator wants to modify the source material, disregarding its increasingly diminishing message. The most important thing is how the play will be received, not what messages it conveys. Krzysztof, isolated in his objections, increasingly descends into the depths of desperation and madness. However, Holland’s film is not limited to the confrontation of idealism with conformism and superficiality. It is also an extremely depressing story about missed opportunities. Equally important is Krzysztof’s wife, Anna (the phenomenal Halina Łabonarska). She tries in vain to save their marriage and capture her husband’s interest. She lives in an unhappy relationship, lacking a nice apartment and a fulfilling job. Holland’s cinematic debut is decidedly one of the most depressing films of the Cinema of Moral Anxiety, filled with unfulfillment and shattered hopes.

Without Anesthesia (1978), dir. Andrzej Wajda

The story of Jerzy (Zbigniew Zapasiewicz), who overnight transforms from a respected foreign reporter into an undesirable element for the system, is as accurate and depressing a reflection on the fate of an outstanding individual in socialism as the much more popular Man of Marble. Jerzy’s life gradually disintegrates—his wife leaves him for his greatest enemy, and his professional position plummets. An invisible, impersonal force opposes Jerzy, pushing him to the margins of society and leading to a mental breakdown. Wajda, without unnecessary euphemisms, depicts the process of destroying an extraordinary individual in the People’s Republic of Poland (PRL) and, importantly, does not reveal the causes of Jerzy’s successive humiliations. This lack of specificity makes the destructive political system appear omnipotent and omnipresent. Jerzy, portrayed by Zapasiewicz at the peak of his film career, refuses to compromise and thus must be toppled from the pedestal, which will be occupied once again by hypocrisy, hand in hand with conformism.

Camera Buff (1979), dir. Krzysztof Kieślowski

Krzysztof Kieślowski focused not only on the pressures that society exerts on individuals and the façade of communist propaganda. Camera Buff is equally a film about the very act of filmmaking and the life of a filmmaker in 1970s Poland. The main character, Filip Mosz (Jerzy Stuhr), is an amateur cameraman who, fascinated by cinema, begins to film his surroundings. Soon, his new passion is noticed by his superiors, who propose he make a film for the anniversary of the factory’s founding. Initially, Mosz’s recordings are purely observational, one might say, innocent, but soon he starts filming what is inconvenient for some. He becomes increasingly interested in the irregularities in the functioning of the surrounding reality and human suffering. However, this does not fit the propaganda of success and prosperity, and Mosz gradually realizes that his film hobby can bring as much harm as good. The hidden actions of the system and the artist’s responsibility are the two overriding themes of Camera Buff. Kieślowski shows that in the PRL, everything functions perfectly only on the surface, while in reality, people suffer. Meanwhile, a filmmaker has extremely limited room to maneuver in such circumstances, which can always prove risky.

Clinch (1979), dir. Piotr Andrejew

The main character, Jerzy (Tomasz Lengren), a railway worker, accidentally becomes a boxer. It turns out that the young man has a knack for his new profession and quite a significant chance of success. Jerzy climbs the ranks of the boxing career but very quickly encounters obstacles in the form of deals, fixed fights, and the unlimited power of promoters. It doesn’t take long for the protagonist to start making decisions about his future—on one hand, he believes in the honesty of the sport, but on the other, he needs money to improve his difficult financial situation. Jerzy is one of many idealists disillusioned by the laws governing reality. His falls are as quick as his rises, but he has no intention of giving up. His mentor, a former boxer who also has a less than noble past, motivates him to fight. In Clinch, Piotr Andrejew shows a protagonist who constantly oscillates between two extremes—honesty paid for with difficulties and poverty, and the other, completely opposite. Jerzy hopes until the end that he can reconcile his conscience with a career as a boxer that demands getting his hands dirty.

Chance (1979), dir. Feliks Falk

In Chance, Feliks Falk avoids explicit political references but clearly suggests them by portraying the school environment as a reflection of the functioning of the Polish political system. The film’s protagonist is Zbigniew (Jerzy Stuhr), a history teacher who cares about the well-being of his students and aims to develop their ability to think independently and make decisions for themselves. A new PE teacher, Janota (Krzysztof Zaleski), arrives at the school where Zbigniew works. Janota, a frustrated athlete, gradually imposes obedience on his students to achieve the best results with his newly formed team. It starts with taking up time that the students should spend in other classes, eventually escalating to blackmail. Zbigniew decides to oppose Janota’s regime, but Janota has the support of the self-interested principal. Falk deserves praise for avoiding the common duality in his portrayal of the world. The two conflicting teachers are not mere caricatures but complex, psychologically nuanced personalities. The metaphor of coercion and control exercised by the state over its citizens is evident but subtly constructed, based on the everyday existence of millions of Poles, not just those employed in education.

The Moth (1980), dir. Tomasz Zygadło

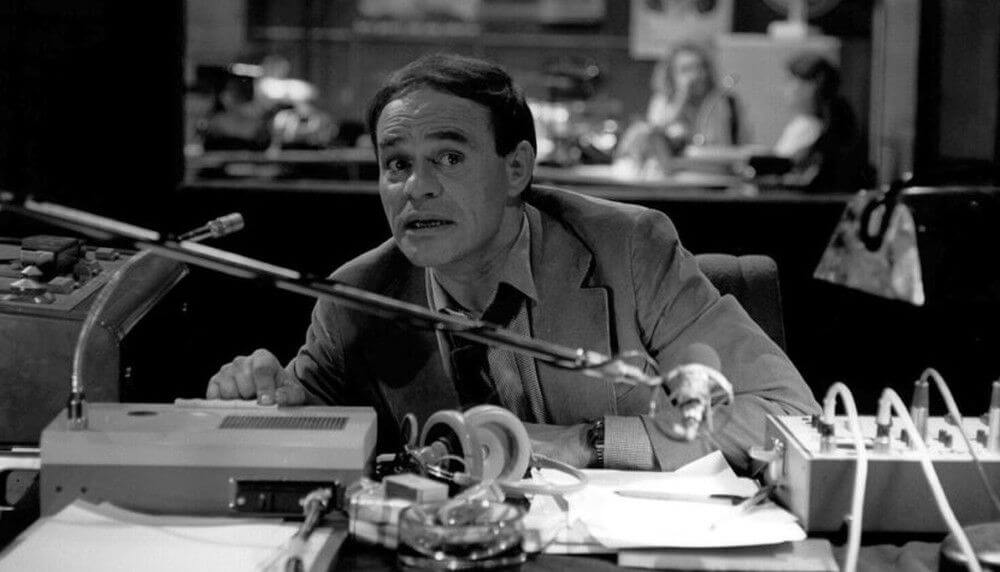

This is one of the most intimate, apolitical films of the entire movement, actually positioning itself on its periphery. The entire story revolves around the main character, Jan (Roman Wilhelmi), who hosts a nightly radio show. Insomniac listeners call him, sharing their problems, even the most intimate ones. Jan tries to help them, support them, and give them a spark of hope. Unfortunately, he himself falls deeper into madness and crushing loneliness. Jan’s situation is not much easier than that of his listeners. He constantly shuttles between his wife’s and his lover’s apartments, just to catch up on sleep and wait for the next broadcast. The responsibility for his problems and those of other people increasingly overwhelms Jan, and his psyche cannot withstand the isolation and sadness. Although Zygadło’s film subtly criticizes politics, mainly through brief episodes with the management, who are increasingly displeased with the show’s nature, The Moth centers on the inability to discuss problems. Thanks to the black-and-white, high-contrast cinematography by Jacek Zygadło, the director’s brother, the film gains a dreamy character dominated by pervasive isolation. The Moth is an intimate portrait of a man struggling with his own problems while desperately trying to help a similarly troubled society.

Without Love (1980), dir. Barbara Sass

Barbara Sass continued the poetics of *Top Dog* in her film debut. The protagonist of her film, Ewa (Dorota Stalińska), also achieves her goals at all costs, breaking up families, taking the place of colleagues at work, and exploiting the innocent. Unlike Lutek Danielak, however, Ewa is a more psychologically complex character. She is a bitter woman with a failed relationship and shattered dreams behind her. She works for a newspaper and strives to climb the career ladder, using not only her inquisitiveness and cunning but also her physical attractiveness. Although seemingly devoid of morality and caring only for her own benefit, Ewa is, in reality, a lonely, disappointed dreamer with a difficult past. Her method of coping with everyday life includes drugs, casual relationships, and relentless pursuit of her goals. The cynical journalist destroys her boss’s marriage, manipulates a colleague in love with her, and exploits a young girl in a difficult situation to advance at her expense. Ewa is corrupt, but behind this facade lies a bitter and unloved desperate woman.

The Constant Factor (1980), dir. Krzysztof Zanussi

Unlike many of Krzysztof Zanussi’s films, The Constant Factor maintains relative coherence, though it still requires focus. The director tells the story of Witek (Tadeusz Bradecki), an employee of a foreign exhibition organization and an avid mountaineer. During one of his business trips, Witek learns about financial frauds conducted by his boss, Mariusz (Witold Pyrkosz). Witek tries to oppose his superior, but his stance finds no support from his colleagues. On the contrary, they start to harass and ostracize him. Witek’s life becomes increasingly complicated, and the prospect of working in his dream profession becomes extremely distant. In his films, Zanussi often addresses universal, even metaphysical issues through metaphor. In The Constant Factor, the director fortunately largely controls his tendencies, making the film one of the most accessible in his oeuvre. The story of Witek’s fate, though relatively easy to follow, still requires intellectual sensitivity. Zanussi wouldn’t be himself if he made a work entirely based on a straightforward cause-and-effect sequence, clear-cut and simple.

Blind Chance (1981), dir. Krzysztof Kieślowski

What sets Blind Chance apart from other films of the Cinema of Moral Anxiety is its narrative structure. The entire film consists of three variants of the fate of one protagonist, Witek (Bogusław Linda), constructed on the “what if” principle. The young man takes a dean’s leave from university and heads to Warsaw. In the first version of the story, he manages to catch a departing train and soon becomes involved in party activities. In the second, he gets into a fight on the platform, leading to a sentence of public works, where he meets opposition activists. Finally, in the third life variant, Witek doesn’t take sides in the political conflict—he starts a family, finds a job, and remains somewhat on the sidelines of all tensions. Kieślowski shows that the titular chance, one small event, can set a person’s life on completely different paths. The film also gathers the paths followed by the creators of the Cinema of Moral Anxiety, proving that behind every person—whether a communist, oppositionist, or neutral—lies a unique, complex story, often full of good or bad choices, coincidences, ups, and downs.