TOP 5 Great MONSTERS in CGI. Balrog, Clover & Others

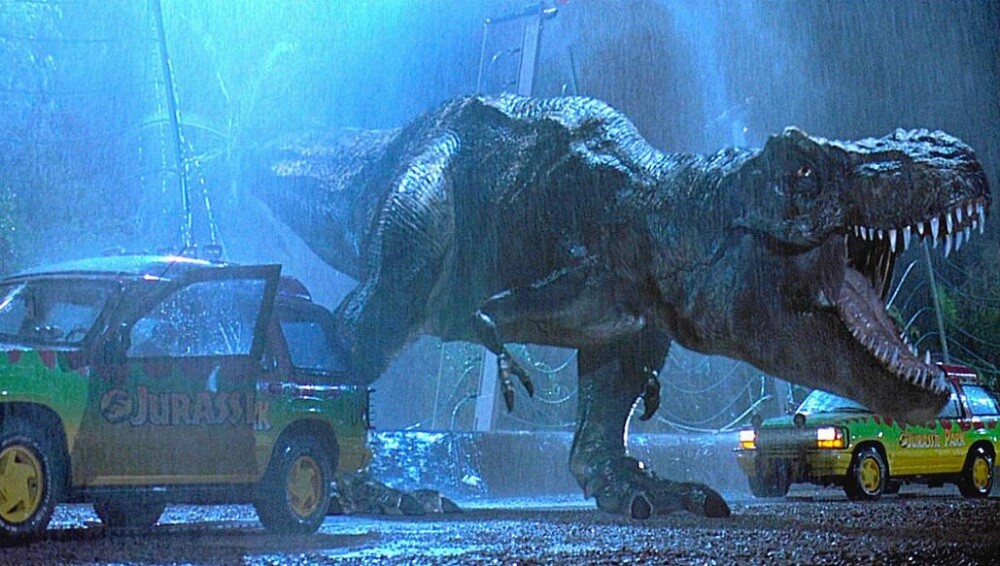

It’s hard to believe that literally in a moment it will be three decades since the release of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. Not only have the special effects from that landmark film aged very nicely, but the sequence of the T-Rex’s exit from its enclosure remains unmatched to this day in terms of the realism of the depiction of the great animal on screen. In addition, an animal created partly according to the old school, because with the help of a 1:1 scale model (nods to Stan Winston’s team), and animatronics assisted only to a small extent by the then still fledgling CGI (computer-generated imagery). As is well known, in the second installment of Jurassic Park from 1997, the same Spielberg already made use of computer effects on a much larger scale and, paradoxically, the dinosaurs of the sequel no longer made such a WOW! effect as the aforementioned semi-analog T-Rex from the original.

CGI effects are the daily bread of modern cinema. While miniatures and animatronics have been stuck in the lamppost for three decades, and are already likely to remain there, almost all screen animals, robots and all sorts of creatures from outer space or fantasy worlds are now the product of a computer, often aided by motion capture (in this field Andy Serkis has reached the level of a master), to render all the more credibly the facial expressions, physics, weight and realism of the movements of CGI creations. Despite the hundreds of films in which fantasy characters have been created to better or worse effect, only a few of them deserve real recognition, infusing us with the extremely realistic illusion of showing an almost tangibly alive creature of flesh, bone and muscle on the screen. Below are five of the best CGI creations, which I personally consider to be the magnum opus not only of the capabilities of the computers of their time, but also of human imagination, creativity and that something magical that made watching these creatures on the screen make me feel again like in 1993, when with goosebumps on my arms I wondered, where the hell did this Spielberg get the real Tyrannosaurus from!

5. TANKER BUG / Starship Troopers 1997 / Paul Verhoeven

As with the T-Rex mentioned literally two lines above, while watching Starship Troopers in 1997, that is, just four years after the release of Spielberg’s blockbuster, I was enthralled by how Paul Verhoeven brought herds of arachnids to life on film. But my jaw didn’t drop until the Tanker, a large bug with a deadly flame-thrower between its feelers, or whatever it was, appeared on screen. I was enthralled by its design, as well as its size (unfortunately, I didn’t dig into the telemetry data, so let’s consider that Tanker belonged to the “big as a barn” category), and its weight-motion credibility, which is often a crutch for digital characters even today – you know, it’s all about that cheesy feeling, as if the characters were too light, hollow inside, thus artificial in the way they moved.

The Tanker was also brilliantly integrated into the action and the interaction with the environment, including Johnny Rico, who, after riding the bug for a while (it still looks better than Legolas on the Olifant) drills through his armor with a hail of bullets and throws a hand grenade (not a holy one, unfortunately) into his nasty guts. The tanker was so realistic that Casper Van Dien (Johnny Rico) fell off his ass during the shoot, breaking a rib. Well, okay, the bug’s ass was a 1:1 scale physical construction, created to show action in close-up, not a computer creation. Today, the special effects from Starship Troopers may not pull you out of your shoes (although I don’t really know, as I recently watched the RoboCop creator’s film while wearing only socks), but they have successfully withstood the test of time, and in 1997 were among the best. Verhoeven’s film earned an Oscar nomination in the Best Special Effects category, going head to head with the Jurassic Park sequel in that category, and fields second only to Titanic, which in that memorable year smashed all the competition with a waltz, sparing only the documentary, animation and short film categories.

4. CLOVER / Cloverfield 2008 / Matt Reeves

How I love the aura of mystery, the understatement, those minimalist monsters even shown on screen, avoiding revealing them in their full glory, in full light. This, among other things, was the key to creating a memorable scene with the T-Rex, where the dinosaur was shown mostly in close-ups, and in detail (eye, teeth, paw in the mud), shrouded in darkness, perfunctorily, where realism was complemented by sound and excellent editing. A somewhat similar treatment was used in an unusual film project titled Cloverfield. This unusual combination of found footage and monster movies, literally had me hooked. Here’s a passably caught with a hand-held camera, a giant (about 107 meters high and 5,800 tons in weight) monster from no one knows where, vandalizing New York City for no one knows why. The army fights it, people run away from it, buildings collapse, rockets fall on it, and nothing can harm the monster. We will see him in his full glory only in the finale, and even then in a distant shot from a helicopter flight, when the beast walks from nowhere among buildings, showered with a hail of bombs dropped on his head by a strategic bomber, probably a B-2 . We won’t see his friendly face until the last shot of the film, and even that will be short, choppy and jerky.

The atmosphere of horror and the eerie aura around the monster is built here with the help of dynamic shots caught with a jittery hand-held camera, and the effect is complemented by eerie noises, some screeching sounds from hell made by the beast. Although we see the monster only in brief snapshots, and rather indistinctly, it’s clear that the CGI specialists have done a great job. The monster is believable, massive, brilliantly animated, in a word, just the way I like it, and one I believe in on screen. Its name Clover is unofficial and it doesn’t fall in the film; the U.S. Department of Defense refers to it by the code name LSA – Large Scale Agressor (I guess in Polish it would be that very large scale of aggression, hue hue). It’s worth recalling that J.J. Abrams himself was behind the idea for the monster, and the film was directed by Matt Reeves, creator of the later Evolution... and War for the Planet of the Apes, and The Batman from 2022. And now for some fun facts behind Wikipedia: The monster’s origin has never been fully explained – fans of the Cloverfield franchise speculate that it is a creature of underwater or interdimensional origin. Clover making his film debut in Cloverfield (in Poland known as Project: Monster) is a small specimen of his species, separated from his family. Overwhelmed by a sense of panic, the creature becomes involved in the destruction of New York City as it makes its way through the city and fights the American military trying to kill it.

The monster was characterized by its tough skin (among other things, against high temperatures and explosions caused by conventional weapons used by the military). In a Blu-ray special edition called Cloverfield Special Investigation Mode, information is given that the monster was eventually killed. The Clover had its own crustacean-like parasites (about 2,000 in number) called by the U.S. Department of Defense under the code name HSP – Human Scale Parasite, whose size rivaled that of an adult dog. In the movie Project: Monster, these parasites preyed on humans, biting them and, after some time, causing the bitten person to feel nauseous, bleed from the eyes and eventually die by exploding their chest. In the 2018 sequel, titled The Cloverfield Paradox, an adult Clover about 2 kilometers(!) tall appears at the end of the film, emerging above a layer of clouds.

3. BALROG / Fellowship of the Rings 2001 / Peter Jackson

The Balrogs belonged to the race of the Majar and were powerful fire spirits who went over to the side of Morgoth, the fallen Valar. Their leader was Gothmog. Most died during the War of Wrath and before, but a few survived it. As Ainur, they clothed themselves in humanoid shapes. In the film adaptation of The Fellowship of the Ring, the last surviving Balrog was depicted as a creature much larger than a human, with horns and a tail. The Balrogs’ characteristic weapon was a fiery whip, but they also used their claws. In the Third Era, the dwarves of Khazad-dum, while mining deeper and deeper for mithril, unwittingly awakened one of the Balrogs. This one killed their rulers (Durin VI and Náin I) and forced the others to leave their abode, which from then on was called Moria and conceived the legend of Paradise Lost. When the Ring Team passed through Moria on its way to Mount Doom in January 3019, the Balrog fought a battle with Gandalf the Grey, resulting in his death. It is known that this Balrog fought with a long whip and a dagger… – That’s Wikipedia, and now me.

Despite being two decades old, the masterpiece of fantasy cinema conjured up by Peter Jackson and New Zealand special effects company Weta Digital hasn’t quite moved it forward with time, but it eats its younger brother – The Hobbit – for breakfast. For me personally, the best part of the LOTR trilogy remains The Fellowship of the Ring, which I’ve been to the cinema three times, and not because I didn’t understand what the movie was about the first time. I chased to the cinema those three times to see not so much the whole, excellent film, but its two best scenes, which made my jaw drop three times, and even today, twenty years later, when I recall them, I have trouble picking it up. With my jaw, by the way, I have a problem even without watching movies, because I supposedly clench my teeth nervously; I think I need to finally seek a consultation with an oral surgeon. Getting back on topic, the first scene that caused the aforementioned dome to drop was the prologue, particularly the bird’s-eye shot of the battlefield and the cliff from which the Orcs fell. The second, on the other hand, was the encounter in Moria with the Balrog, inflamed with anger….

The capably created, powerful, majestic, flaming beast was shown on screen in an extremely spectacular and realistic way, and its fiery roar, when the camera almost looked into its maw, reminded me vividly of the roar of Spielberg’s T-Rex, whose spirit, as you can see, accompanies us all the time. When this hell with wings called the Balrog, crawled on two flared paws behind the heroes, stomping solidly, shivers ran down my spine, seriously. Not only the graphic designers did an excellent job here, but also the sound designers, creating one of the most memorable on-screen badasses. And adding to that the iconic Gandalf’s You shall not pass!, and the later sword-fight with the Balrog in a diving flight (shown a year later in the opening of The Two Towers), yes, the Balrog is solidly in my cinematic memory. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any information about the weight and height of this Ghost Rider’s great-great ancestor, that is… actually, I found the technical data of some Balrog from the Street Fighter game, but he measured 1.98 meters and weighed 102 kilograms, so he would be too light, and shorter than Gandalf in the hat, so it’s rather not that Balrog. All joking aside, let’s just recognize that the Balrog was relatively large, but also quite a bit smaller than the other monsters in my ranking, and the kind of Leatherback from the second place below would at most get burned in the foot by trampling the Balrog, extinguishing it like an underdog.

2. LEATHERBACK / Pacific Rim 2013 / Guillermo Del Toro

First, some stats, taken from the Pacific Rim fandom. The Leatherback is a Category IV Kaiju, measuring 71 meters tall, and weighing 90,000 tons. Leatherback’s fists are like mace; the hard protrusions that cover them can pierce through armor. Its thick skin allows it to withstand heavy damage. It is further reinforced with bone armor on its shoulders, and a comb-like plate that covers the top of its head. It has fourteen bioluminescent whiskers on the back of its head that move as a sign of agitation. He is slow, and his strength lies in his fury. His movements are reminiscent of a gorilla walking on the knuckles of large, shovel-like hands, or making great leaps. It has six visible eyes. The most deadly feature of this Kaiju is a large, four-lobed organ on its back that can naturally charge and generate an electromagnetic pulse that disables all electronics over a wide area, a dangerous threat to digital Jaegers, but not the analog Gipsy Danger.

Let me start by saying that Guillermo Del Toro’s film about giant Kaiju attacking Earth’s metropolises is undeservedly somewhat forgotten today. In addition, already at the time of its release it didn’t get the recognition it deserved, losing the duel of popularity with Michael Bay’s Transformers series, which ruled the public’s imagination at the time. Of course, I’m not talking about the plot, rather pretextual and trivial, nor about the acting, merely correct, but about the visual and sound side, which, in my opinion, was a true technological masterpiece; I regret to this day that I didn’t see the film in an IMAX theater. I will skip the capably animated Jaegers here, going straight to the insanely realistic depiction of the gargantuan size of the Kaiju. Here you can see and feel the enormous mass, and the monstrously great energy these creatures must use to move (often very dynamically and quickly) their huge bodies. My absolute number one remains the bone-healthy, epically nasty Leatherback, with which the heroes at the helm of Gipsy Danger muggle on the docks of Hong Kong. This mega-monster, after a brief warm-up in the ocean waters, enters the ring (the aforementioned docks) in spectacular fashion, as, coming out of the water, he tramples, in a fiery explosion under his boot, a semi-trailer truck parked on the wharf, like a child’s toy – one of my favorite parts of Pacific Rim, by the way, accompanied by epic music.

I love revisiting Leatherback’s duel with Gipsy Danger because of its, so to speak, meatiness and general honeyedness, which allows me, as a viewer, to be entertained like a piglet. On top of that, it’s the only time a Kaiju uses man-made objects (a crane arm) as a weapon, though in retaliation it quickly gets hit in the stupid snout with containers wielded by Gipsy Danger. Both this majestic-titanic clash and the entire film are a true display of realizational genius by the team creating a technically dazzling spectacle (effects, sound, set design), for which they did not even receive an Oscar nomination. Gravity reigned supreme at the gala, while nominations for best special effects still went to Iron Man 3, Star Trek. Into Darkness, The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, and attention, this one will hurt – The Lone Ranger.

1. M.U.T.O. / Godzilla 2014 / Gareth Edwards

I know I’m well into my 40s, and as an old guy it’s inappropriate for me to write this, but in my more than three decades-long adventure with cinema, only three things have realistically given me the creeps and scared me: the youngster from Kubrick’s The Shining walking toward the door grunting REDRUM, Dario from Blinded by the Lights (Polish series), and just M.U.T.O. (Titanus Jinshin-Mushi species) from Godzilla. Its name, so similar to TV sound muting, is taken from the first letters of the term Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organism. When creating M.U.T.O., Gareth Edwards and his design team looked to monster characters from such classics as Jurassic Park, Aliens, Starship Troopers and King Kong for inspiration, wondering what made those monsters and their designs iconic. The director also had one important wish: that Godzilla’s antagonist should be, whatever he had in mind, a modern monster for its time, and indeed, this seems to have happened, as it’s hard to find anything to M.U.T.O. similar, both in the earlier and later history of monster movies. It took a total of nearly a year to design this oddity that cuts nuclear warheads for breakfast, with Weta Digital, among others, having a hand in its creation. The spectacular birth sequence of the huge male, after he had already charged his batteries with energy from the nuclear reactor, I watched, not to lie, some 20 times, or, counting quickly, 19 times more than the film as a whole.

This amazing monster, boasted a weight of 15,000 tons and a height of 60 meters; the much larger female weighed 60,000 tons and measured 90 meters. Its design, especially the bug-like head from Starship Troopers, which was capitally created by the graphic designers, is simply amazing. This fearsome, stooping creature on six of its eight limbs (two of which are folded wings, designed, incidentally, to mimic the flap of an F-117 Stealth fighter), is devilishly strong, very realistically animated (you can feel its impressive weight), and commands respect in the divisions, as even Godzilla has a lot of trouble with him. The scene of his exit from the trap surrounded by steel ropes is, for me, the spiritual heir to the T-Rex, mentioned several times in this text, getting out of the enclosure in 1993. The effect of the awesomeness of this, my absolute favorite movie monster, is complemented by its rumbling slap of a leg on the ground, causing an electromagnetic pulse to be sent out, shutting down the electricity within a radius of few miles. And a kind of icing on the cake is the fact that this winged egomaniac can drag a submarine out of the ocean, just to feed on the nuclear warheads gouged out of its interior. To sum up, for me, Godzilla (although also coolly and climatically presented) is in Gareth Edwards’ film a background for M.U.T.O., who, steals every scene from the king of monsters.

For much of the film, M.U.T.O. is shown in dark, perfunctory, short shots (much like Godzilla, by the way), only whetting the audience’s appetite for more. I like this kind of unsatisfactoriness very much, not very common in today’s cinema of attractions, where it is replaced by overkill. This parsimonious, minimalist way of showing the monsters in the blockbuster, especially in its first two acts, was unfortunately the reason for Godzilla’s poor reception in theaters. Viewers felt cheated in some way, as scenes with monsters were cut off at the best of times, or they were shown fighting in snapshots on TV shows. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was probably of a similar opinion, as evidenced by the lack of even an Oscar nomination for special effects. At the time, Interstellar won, while Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Guardians of the Galaxy, X-Men: Days of Future Past, and Evolution of the Planet of the Apes were still nominated). I consider this a scandal, for M.U.T.O. alone deserved to walk away with a statuette in its teeth!