THE DRAMA OF CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC. Without stylish melody and not memorable

Apparently, the older one gets, the more they complain. Some believe it’s a symptom of progressing infirmity, not only physical but also a sense of losing control over one’s surroundings, leaving behind only painful memories of what once was. In the case of complaining about music, I’m not quite that old yet, but I do complain because I’ve been listening to film music for years, and because over the years, I’ve gained a broader view of the processes happening within it. It reminds me of an apple, delicious and beautiful, which is devoured to the core by a disgusting, stinking, slimy worm of mediocrity and pursuit of money. Besides, I think I’ve complained the least about film music – not like about “Starship Troopers” – although I have occasionally criticized the contemporary mediocrity of musical themes written for films, especially after 2010. Something has certainly changed for the worse in contemporary film music, the kind that sticks in the memory forever, the kind I used to collect on cassette tapes to listen to with immersion through headphones, as an independent story rather than just an illustrative element of a specific film, even of the most beloved.

Is it a tragedy? I don’t intend to dramatize it that much, although I lament this phenomenon, even though nothing wrong has happened from the definition of the function of film music. The illustrative function is the primary role of film music, although over the decades in the history of cinema, it has varied. Illustration has always been present, but its melodic form has evolved, either moving away from or towards the idea of musical drama, from which film music directly derives. For those now thinking that musical drama might be opera or operetta, I’ll just say that it’s quite the opposite. The difference is best seen between Richard Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde” and, for example, Giuseppe Verdi’s “Nabucco.” I deliberately won’t explain the definitional differences between these genres because it’s enjoyable to discover them by watching these specific performances rather than memorizing rigid rules. All the information is available online for the curious.

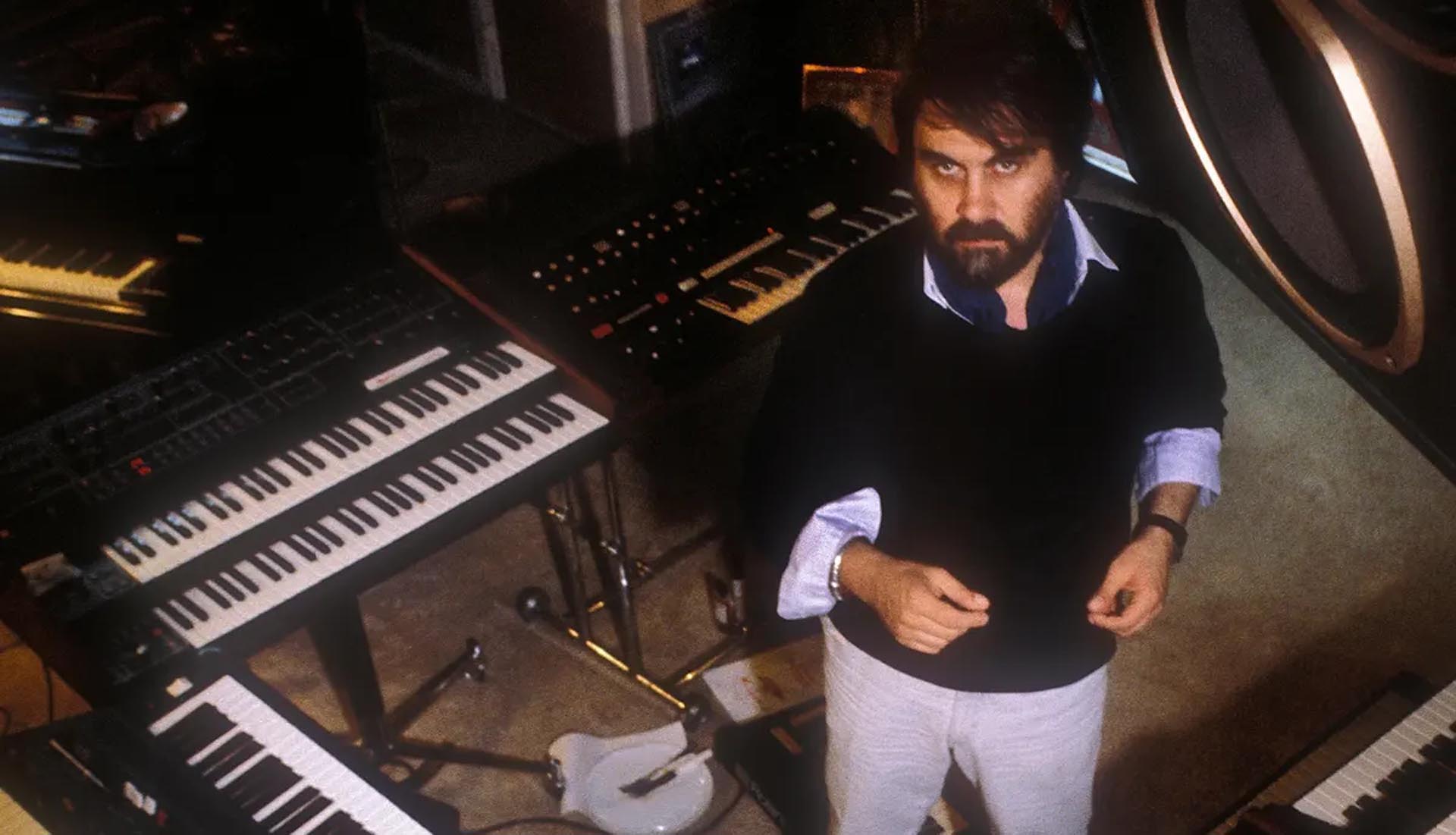

Film music primarily took from musical drama the use of the leitmotif technique, its repetition, rearrangement, and fragmentation, accompanying the film image. Melody, as well as the scale and tonality used, depended on the times and the prevailing style. And this is what I mean by the SUCCESSION OF SOUNDS possible to remember or not – more illustrative, because it complements the image and does not dominate over it – or able to function as a separate musical story from the scenes in the film, stimulating the imagination with impressions received solely through the sense of hearing. Some composer spends more or less time over it, or maybe doesn’t need to at all because they have the talent to compose a masterpiece in 5 minutes. Provided they know the notes, unlike Vangelis, who had no clue about them, which can’t be said about Philip Glass. Right now, I have their musical notations open on my monitor, illustrating two completely different approaches to film music, one strictly illustrative and illustrative-melodic. I don’t particularly care about the type of melody in this context. Vangelis mixed various types of melody in his improvisations. He was diatonic, cantabile, arc-shaped, and diatonic. Glass, on the other hand, was minimalist, tremolo-based, and sometimes chromatic, but also tremolo-based like Vangelis, albeit within a much narrower range of sounds and tonics. Speaking of the musical compositions I’m looking at, they are Vangelis’s “Memories of Green,” written in D major, and – heavily phrased – with changing meters from 4/4 to 3/4, and even 3/8, which can be heard beautifully when the sounds of the piano synthesizer rise and fall, and Philip Glass’s “Prophecies” from “Koyaanisqatsi,” written in regular C major, which sometimes twists into A minor, without phrases, with complicated dynamics, in 4/4, with legato eighths, triplet groups, and heavy, monolithic whole notes sustained on the pedal in the left hand. I spent hours struggling with similarly notated etudes to play every note correctly while keeping the rhythm. It resembles the struggle of life, constantly fighting, changing, evolving with tiresome stagnation, resignation, and death.

Both of these worlds have immense cinematic significance, yet only one is memorable – that of Vangelis. It’s creative and inspiring, while Glass’s seems more like contemporary art devoid of emotional significance. The drama of today’s film music lies partly in these two worlds. On one hand, it fulfills the illustrative function more strongly than ever, paradoxically by using means as predictable and worn-out as chords and their inversions used in disco-polo music. Let’s compare the sugary tunes in, for example, “Man of the Future” composed by James Horner, who bizarrely ripped off himself from “Braveheart,” and the magnificent score from “Sophie’s Choice” by Marvin Hamlisch. The former melody is hardly remembered at all because it’s a boringly rehashed theme from a past hit with Mel Gibson, while the latter is listened to with delight, experiencing every stroke of the cello bow on the strings.

Unfortunately, contemporary blockbusters are full of such musical banalities. They lack intelligent, memorable, and highly individualized themes that serve both an illustrative and independently emotional function, as was the case in the syncretic approach to opera and musical drama genres. The situation with music mirrors the situation with films in general, where the visual form overshadows the content, using expression means that we have seen many times before, safe but packed with special effects to cover their mediocrity and plagiarism. Thus, the drama of contemporary film music lies in the lack of a musical theme that would dominate the entire soundtrack – a theme that shouldn’t be just 4 notes, but a complete phrase with melody, harmony, and rhythm. A theme that requires ideas and talent, which undoubtedly characterizes the work of John Williams and, for example, our Polish composer Michał Lorenc. Sometimes it’s better to fill a film with tons of meaningless songs composed without regard for the image than to make the effort to find a creator who understands the production, watches it repeatedly, and composes a soundtrack that will go down in history.

Returning to “Starship Troopers” mentioned at the beginning, Basil Poledouris’s music stands out in quality throughout the production.