Ridley Scott has already made a film about Napoleon. And it’s much BETTER

Ridley Scott does not seem satisfied with the reception of his latest film. The fate that befalls those who decide to criticize Napoleon is essentially the same. The British director accused historians pointing out errors and factual inaccuracies in the film of “not having a life.” He did not spare them bitter words in an interview for the London Times, openly admitting that he asks the same question to every dissenter with a university diploma: “Were you there? No? Then shut the fuck up.” When French critics attacked the film, Sir Ridley also responded with fire, once again acknowledging – just like Napoleon at Waterloo – that the best defense is an attack. “The French don’t even like themselves,” he declared in an interview with a BBC reporter.

When his films fail, the Gladiator director presents a prime example of the besieged fortress syndrome. He barricades himself more tightly than Jerusalem in Kingdom of Heaven, then goes on the counteroffensive. I vividly remember two years ago when the disturbingly weak box office performance was achieved by an otherwise genuinely good film, The Last Duel. Scott then blamed the entire failure on the “spoiled millennial generation” (confusing it with Generation Z), raised on those “fucking smartphones. Millennials don’t want to learn or find out anything unless it’s on the screen of their phone.” Ironically, a few months later, the Brit filmed an advertisement for the new Samsung Galaxy – entirely using the camera in the smartphone.

And again, Scott’s arrogant behavior resembles that presented by the filmic Napoleon. In one of the final scenes of the movie, Bonaparte instructs young British cadets, proclaiming that the most challenging part of life is “accepting the mistakes of other people.” “I would admit to a mistake, but I’ve never made one,” says the French emperor a moment earlier. Scott has more in common with his hero – whom he both admires and treats with clear reservation, comparing him in interviews to Adolf Hitler – than he would care to admit. Give him a few more years, a few poorly received projects, and a few uncomfortable questions, and he’ll start throwing fictional quotes from Bonaparte. He will never publicly admit that he made a simply unsuccessful film. Inconsistent in terms of character psychology, tiresome in reception, historically distorted, carried by a few successful battle sequences – that’s precisely what the monumental Napoleon is. A giant on clay feet.

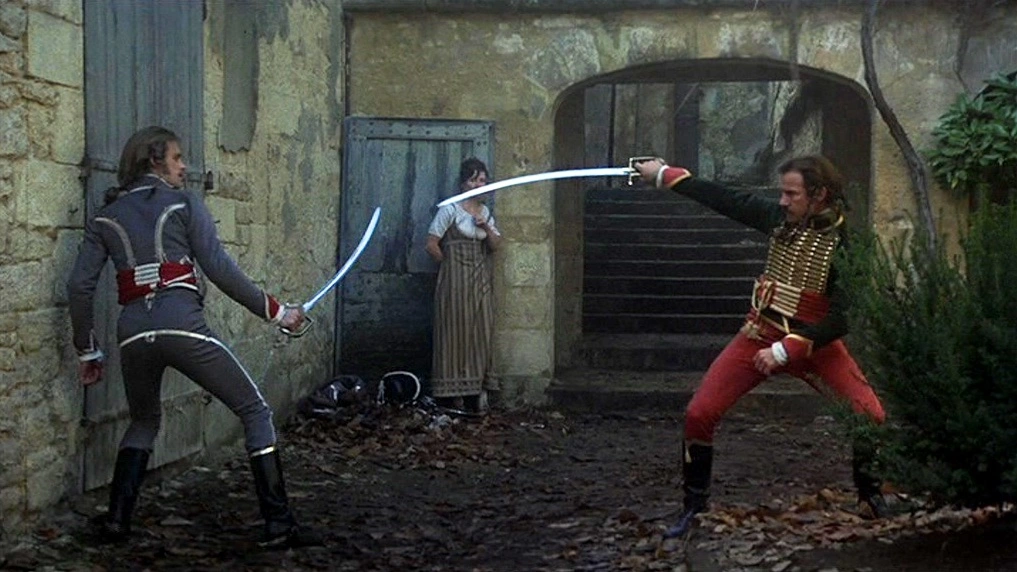

The failure of Scott’s new project seems even more interesting when considering that the era of Napoleonic wars is ingrained in the filmmaker’s DNA. The action of his first feature film, The Duellists in 1977, took place precisely during this particular historical period. Borrowed from Joseph Conrad’s story, the narrative focused on a series of clashes between two officers of the French army – Armand d’Hubert (Keith Carradine) and Gabriel Feraud (Harvey Keitel). For various reasons, the characters could never complete the titular, life-and-death duel – so every few years, they would make another attempt to kill each other, while traveling with Napoleon’s armies across Europe (one sequence is even set during the infamous invasion of Russia).

Drawing on Conrad’s literary prototype and Gerald Vaughan-Hughes’s screenplay, Scott told in his debut about unrestrained conquest, driven by a gigantic ego. The hidden but crucial character for the meaning of the The Duellists was none other than Napoleon: an exceptionally talented commander, undone by pride and excessive ambition. In Scott’s film, Lieutenant Feraud – an excellent fencer and hardened Bonapartist, who, besides fighting, most enjoys being proud – is a clear stylization of Napoleon. He agrees not only on the semi-legendary height but also on attire: the most important visual component is, of course, the famous bicorne. When Bonaparte is ousted from power, and supporting him becomes unpopular in France, Feraud does not renounce his views, for which he ends up in prison for a while. Like Napoleon: he returns to finally test his luck and face his eternal opponent. Ultimately, Keitel’s character shares the fate of his idol – the last scene of the film intertwines their destinies indissolubly by referencing František Xaver Sandmann’s famous painting (Napoleon on the island of St. Helena).

Whether he likes it or not, Ridley Scott outlined a camouflaged portrait of the Emperor of the French in The Duellists – much more interesting and coherent than the one he presented in his new film. The plot of his debut works perfectly on both a literal and allegorical level. For d’Hubert, the conclusion of the series of duels with Feraud is exactly what the end of the Napoleonic Wars was for Europe: a moment of relief, ecstatic happiness after dealing with the demon. Carradine’s character, unlike Keitel’s, matures with each subsequent duel – the series can only end when he has something more to lose than just his own life.