“Fallout” is a surprisingly good adaptation. Today, there’s no need to steal games, although war is near

This is the irony of our times and my teenage life—that I had to go through some serious acrobatics just to play Fallout 1 and 2, having virtually no means to buy these games. Cracks, keygens, exe swaps, mounting images on virtual drives to simulate original discs, that finger-twitch on the left mouse button hoping the game would start this time and the saves would be intact. When I turned 18, things turned upside down because playing such politically incorrect games was part of our generational rebellion against the philosophy that you have to have before you can be, so we stole everything that seemed iconic. Thanks to this hustling, I had the chance for Fallout 1 and 2 to shape my image of the computerized (and more) post-apocalypse for life. I waited many years for a movie, a series, anything, thriving with Fallout 3 and 4. I finally got it, between my forties and fifties, and I’m okay with that because it’s a great production. It soothes my old, twisted world experienced during the regime’s transformation, giving it a little more childish fuel to cross half a century and see the first contours of retirement looming on the horizon. On the other hand, I’m astonished and saddened that we seem to be stuck in one place when it comes to envisioning our end—specifically games, films, books—the narrated model of human genocide remains the same. I also fear that the niche nature of the Fallout universe will now be transformed into a profitable franchise, thus commercialism will destroy the most important advantages of this RPG reality.

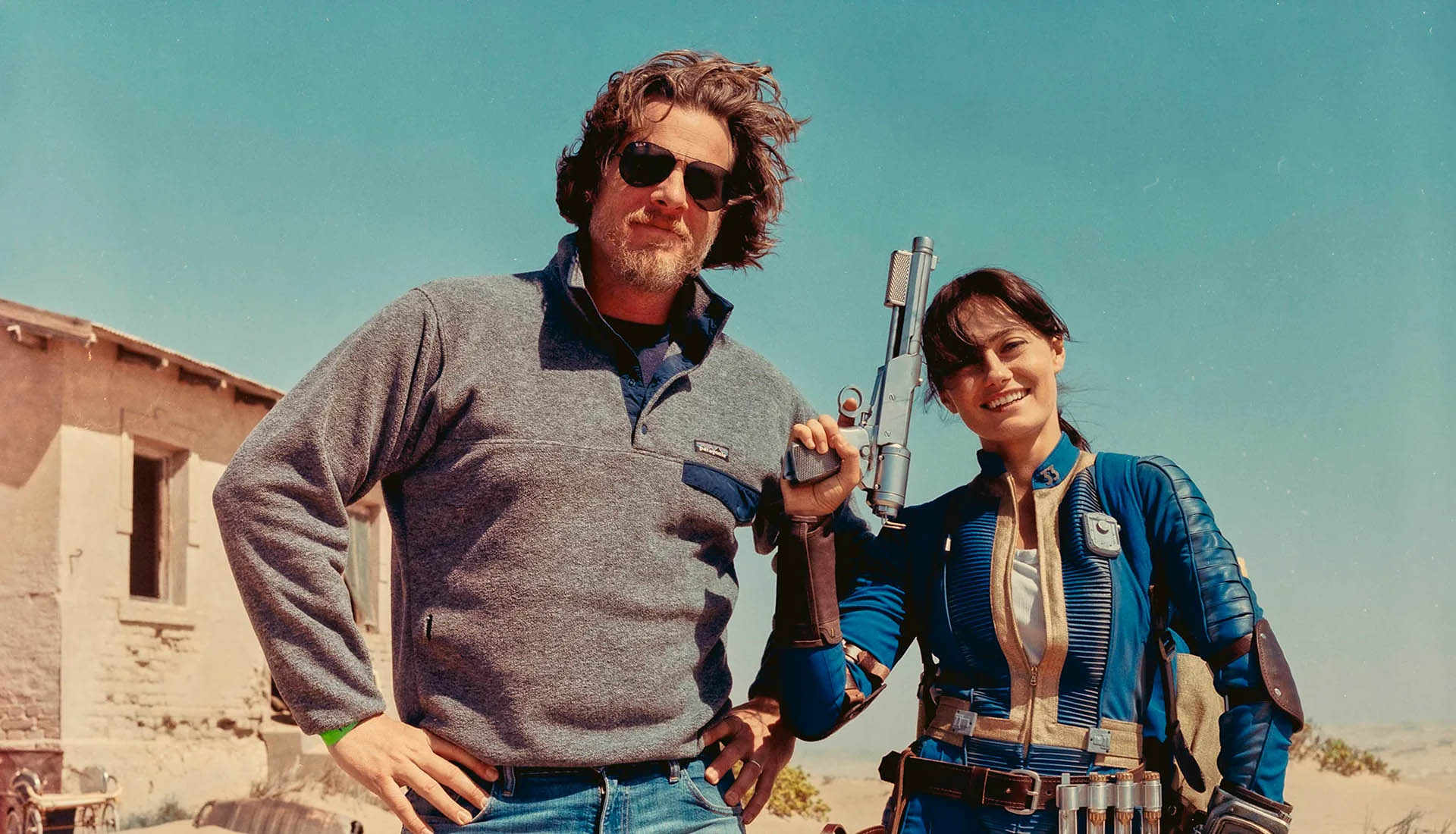

I’ve already found ads online promoting gaming chairs with the Pip-Boy logo. Prices for the latest Fallout versions with add-ons have also dropped at the Xbox store—that’s a relief. However, my local grocery store still doesn’t sell Nuka-Cola. Yet, it’s evident from the market that traders who usually have no clue about the magic of the universe they trade in are already eager to extract money from Fallout fans, preying on their sentiment. To younger generations, they’ll sell gadgets always because the apocalypse is popular today, as if we were living in a new fin de siècle era. Despite these commercial concerns that Fallout will become a franchise losing quality with each season, it’s surprisingly good for now. I didn’t expect to see such a well-crafted storytelling of the game world. Amazon went above and beyond, perhaps because they had specialists from Bethesda Game Studios overseeing it. After the release of Fallout: New Vegas, made by Obsidian Entertainment (former Black Isle Studios employees), Bethesda had a debt to repay to older players who never fully trusted the company to carry the title. After all, Black Isle are the legendary creators of the first two Fallouts. They had to keep up, proving themselves not just with games, but by creating a whole cinematic universe, of which the Amazon series is an important beginning. Bethesda passed this exam.

Was it difficult? Adapting games is much easier than books because with literature, you only have words that need to be converted into concept art. With games, filmmakers can use gameplay as draft graphics. The problem lies in writing the story, as game storytelling follows different rules, and viewers probably wouldn’t want such a direct copy. Therefore, the Fallout series is a well-executed homage to the game aesthetics while taking viewers on an entirely new journey in the universe, perhaps to suggest a further path of game development. That would be an interesting role reversal.

As for aesthetics, the original concept was fantastic. The series is set in the United States, but it’s an entirely alternative path of their development. Most importantly, transistors were never invented. Vacuum tubes and atomic physics are the basis of science, leading to a stagnation in societal development akin to the 1950s. Interestingly, certain scientific elements progressed and influenced culture, while others did not. There’s also the lingering Cold War paranoia mandating the eradication of any communist tendencies in society, which ultimately led to war. The key event shaping Fallout is the Great War, a global nuclear conflict between the United States and China in 2077. The series depicts this interestingly—both the science and the morality—through the retrospective of the life of the ghoul Cooper Howard. I’m not a fan of retrospectives, but these are engaging and infrequent, thus not disrupting the main narrative flow. The series unfolds 219 years after the Great War, in 2296. It might seem odd to many that over two centuries passed without Earth being rebuilt, primarily due to Vault-Tec’s pre-war activities. They built 122 vaults where people were supposed to hide from nuclear attacks, but in reality, it was to create a new, better, and more Nazi-like society. However, the experiment persisted, and its consequences are explored from the 6th episode onwards. The journey to Vault 4 is shocking for the characters and accelerates the narrative pace, adding horror elements to the post-apocalypse for viewers. Multigenre storytelling can be chaotic in modern productions, but in Fallout, it’s an asset. The same goes for the antagonists—many are evil, many are good, much like in RPGs. Depending on our choices and others’, we become villains or heroes, and our friends can become potential enemies.

One can argue if the world depicted still looks the same after 200 years as in the series—reminiscent of Mad Max. It’s a spectacular move creating atmosphere. Radiation could also explain the situation, preventing recolonization. Comparing the timeframes of the series with the games, they span 185 years in post-war history, with the first game occurring in 2102 and the last in 2287. The Amazon Prime TV series takes place right after the events of all Fallout games in 2296, significantly expanding the world’s timeline. Since these events aren’t in the games of that period, the storyline wasn’t limited for the creators, and they made clever use of it.

Regarding aesthetics, both pre-war and post-war elements are faithfully recreated from the best aspects of the games—from vaults’ interiors to the doors leading to the outside world, Pip-Boy, Vault-Tec mascot, kinescope TVs, stimpacks, vault dweller outfits, mutated creatures from the world above, ruins of old California, all details of attire and weapons, like the iconic Brotherhood of Steel knight helmet, and even the food—especially the famous jelly. Maximus, Lucy, and Ghoul are surprisingly unique additions complementing this aesthetic. Most importantly, although I know it’s nearly impossible, there’s a sense that character attributes grow as in RPGs after completing quests. Lucy is a prime example when she completes a task in the Superdupermarket, which is actually a human organ harvesting facility, and her stats significantly improve. Maximus also levels up, and as for Ghoul… his transformation is of a different nature. It somewhat reminds me of Arthur Morgan’s character development in Red Dead Redemption 2. I won’t reveal more; discovering it for oneself is enjoyable, especially the finale. The violence and language are at a high level of indulgence. There’s even nudity, though women are portrayed too safely for the series to be considered daring. Since games had no limits, why impose them in the series? Perhaps a fear of losing viewers? The age rating should be raised to 18+ to solve this formally. I’m especially referring to Lucy’s first encounter with her husband at their wedding, where she doesn’t remove her dress at all, and the groom is immediately naked. It looks strange. Hopefully, game fans won’t object to the expanded relationship plots in Vault 33, 32, and 31, which lean more towards detective drama than post-apocalyptic themes. The games approached this differently. Moral choices were abundant but less intertwined with diverse atmospheres. The series needed a non-linear plot to engage viewers with twists and, most importantly, to distinguish Fallout from The Last of Us. I’ve seen these comparisons online, and Fallout likely ranks higher than Naughty Dog’s hit. Fallout is much more political, anti-war, anti-utopian, social-democratic. The discussion about not allowing dogs in vaults between Howard and his wife is a great example of the series’ libertarian message. What’s the point though? We make so many productions about future dangers, but does it bring about any global change?

Returning to the earlier suggestion that we’re going in circles, contemporary mass culture replays entertainment models designed mainly in the 80s and 90s. In this context, something from Fallout comes to mind—the end of the world is a product. It just needs to be managed appropriately, and if a method is found, time almost stops. Cultural management as well. It’s like managing fear, a craft we know masters of from history. Another, darker thought crosses my mind. We’re probably close to the end of civilization since the canon of human extermination hasn’t changed in over 30 years and is now entertainment for us, increasingly so. We keep telling ourselves the same cliché about our end, and I’d like contemporary pop culture to have the courage to abandon our old dad narratives, who stayed up all night to do one more quest in a game that determined our imagined independence because they had to get up in the morning, attend classes, and pretend to be good students at least until 2 p.m. I never expected to write this in the context of games and a series about total war, newly aware that I’m living in a pre-war era. Maybe that’s why we talk and think so much about war, play it, enjoy collecting frags—to prepare for its real arrival? It’s very close.