THE HUNGER. Much more than just vampire horror movie

…. even if you take into account that fear and excitement are two surprisingly closely related emotions. Tony Scott’s The Hunger is sometimes classified as such, but that’s a misleading definition, even though the film does contain one of the most sensual scenes in the history of cinema.

The Hunger, Tony Scott’s full-length debut focuses on something much deeper – on a blind, destructive, and uncontrollable need, on an overwhelming desire that flows from wild instinct. And we’re not talking about a thirst for blood, but something much broader and closer to all of us.

The Hunger begins with a sequence in a nightclub. Peter Murphy, the leader of the band Bauhaus, today recognized as a pioneer of gothic rock, sings the legendary song Bela Lugosi’s Dead. His expressive performance is equally unsettling and hypnotic, like a dark mantra: “undead undead undead…”. Two new people arrive at the club. She and he, just one look at them is enough to see that they are connected by a strong intimate bond. They are Miriam and John, here for the hunt.

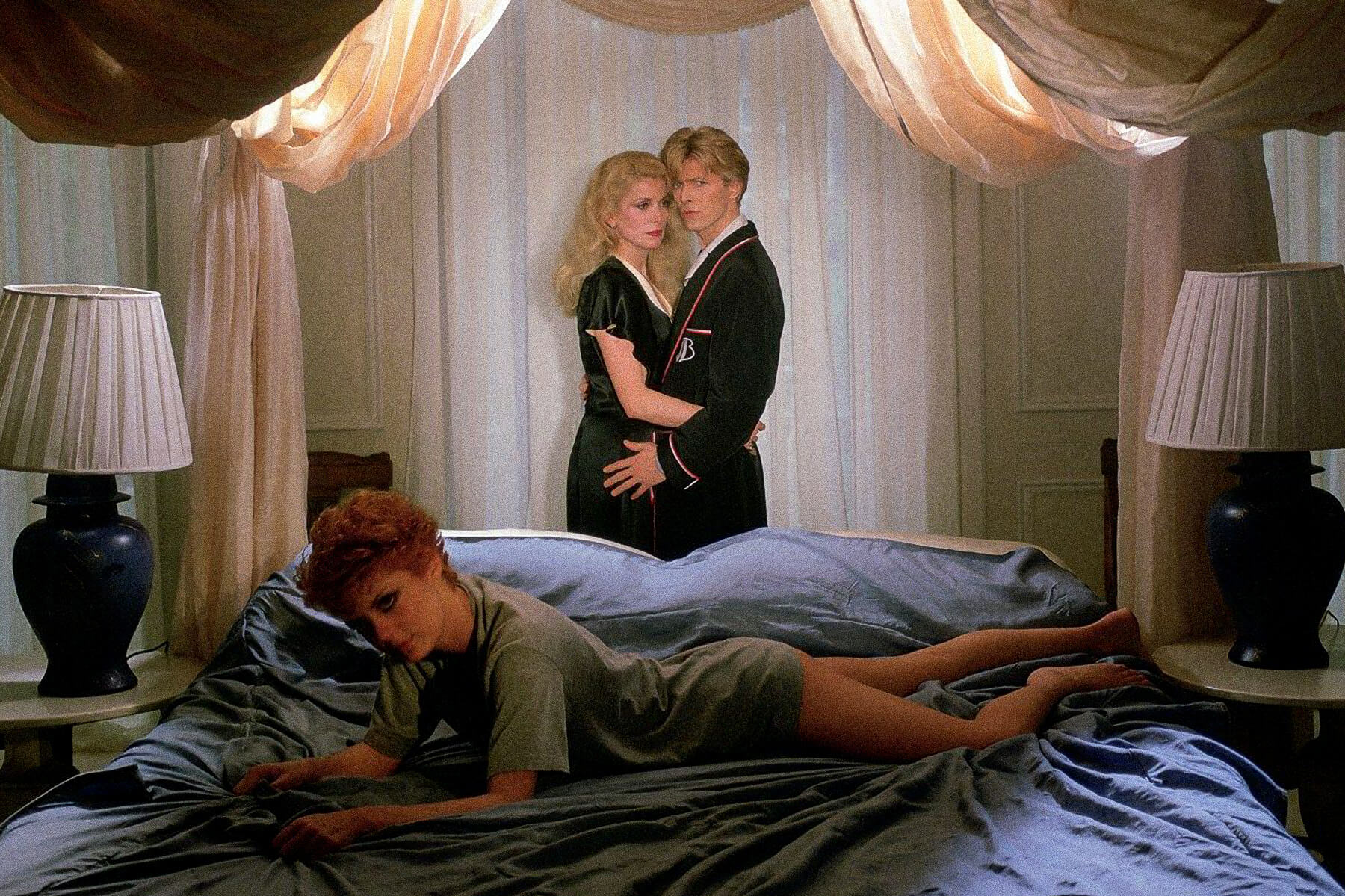

This couple has been living together for three hundred years, they know each other perfectly, and they know everything about each other – or at least, he is under that illusion. When he accepted the gift of immortality from her, they swore to each other that it was forever and for all eternity. Perfect love, two people bound by a dark secret for eternity against the world. But something is wrong. John has been having trouble sleeping for some time, his hair is falling out, and he notices small wrinkles around his eyes. His youth is ending. He knew it would happen, but he can’t come to terms with it. It’s happening too fast. Desperate, he seeks help from a doctor specializing in progeria research, Sarah Roberts, who dismisses his pleas. In an act of despair, he attacks a friend and ward. All in vain – John is doomed.

Miriam loves John, of course. She loved all her partners, and her life dates back to ancient Egypt, so there were many of them. Men and women. There is one thing, however, she never told them: that their lives were the condition for her youth. John, too, will be condemned to an eternity of torment so that she, Miriam, can find a new partner. Her regret, her despair is sincere. Her pain is authentic. However, the desire for survival is stronger.

In essence, each of us, at some point in life, faces the loss of something that seems essential for survival. It’s at that moment our primal instinct awakens, and at its core is selfishness. We want to hold onto what’s valuable to us at any cost. The feeling, even in its withered and tainted form. The person we’ve come to consider the center of the universe. Youth and beauty ensuring success. Material status. Family. Childhood. Sometimes even a beloved object. We cling to it feverishly, just to prevent it from slipping away. Fear envelops us. The instinct of possession and survival kicks in. It’s as strong and painful as hunger. And it demands satisfaction just as intensely.

Even sorrow and shame cannot defeat this overwhelming feeling. The awareness that we’re hurting someone, that we’re draining them step by step, that we’re trying to draw from a source that’s drying up. It’s an addiction demanding satisfaction. The more we succumb to it, the greater its influence on us. At some point in life, we all become incurable egoists. Sooner or later, each of us will have to confront this. We might come to hate ourselves then. Or maybe we’ll yield to our instinct calmly. We might fight and lose. Or perhaps, despite everything, we’ll emerge from this battle intact, because, in addition to instinct, we still have dignity and humanity.

The existence of primal egoism, the desire to preserve what we consider essential for life – even if it’s not objectively so – is undeniable. However, whether we succumb to it or make a firm stand against it depends on who we are and who we aspire to be. It may turn out that by yielding to ourselves, there comes a point when we become pitiful and caricatured. Look at Miriam’s face, that calm, cool, classically beautiful face. Her impeccable style, elegant high heels, and refined veil. Slim fingers holding a cigarette, perfectly painted lips, swaying hips, elegantly crossed legs. The painful sadness in her eyes, which have seen too much already. And yet even she, the ideal woman, the immortal woman, the eternally beautiful woman, may suddenly encounter something that reduces her to the role of an animal, brings her to her knees, shatters the entire perfect facade.

Some film critics, after the premiere of The Hunger, criticized this strange transformation with distaste. They expected a stylish vampire horror and expected the familiar Catherine Deneuve image. After all, she’s the first lady of French cinema, right? It’s lovely to see her in the role of a seductress, but not so much crawling on her knees. It’s so… ordinary. However, the brilliantly depicted decline of Miriam is one of the most moving aspects of the film and the essence of its message. Kudos to the great actress for not being afraid of it. It’s not a coincidence that in The Hunger, the word “vampire” is never uttered. We’re not talking about vampirism. We’re talking about humanity.

Just as wonderful as Catherine is her screen partner – David Bowie, as John. He rarely appeared on screen, but when he did, it was with a bang. The way he portrays the drama of his character, going through the accelerated phases of aging, deserves all the world’s awards because makeup and costumes are just one element of this process, and not the most important one.

And finally, Susan Sarandon, as Sarah, a young doctor slightly lost in her own desires. Sarah wants, yes, to savor life as intensely as possible. Yes, she feels like she got lost somewhere along the way, denying who she is and what she desires. Nevertheless, Sarah also refuses to live in the clutches of addiction. It debases her, and she is resolute about it. The character of Sarah reminds us that we have the right and the ability to resist instinct, even if it’s painful, and even destructive.

Unlike the critics, having an awareness that The Hunger is definitely more than just an “erotic horror,” Sarandon was very disappointed with the ending, considering it distorts the whole idea of The Hunger and her character in particular. And it’s hard to deny her that. The ending here is the biggest flaw, like an accident at work, a grating contrast to the stylish, well-crafted, well-thought-out whole. However, if you imagine that the ending happened a few minutes earlier, you get a wise, bitter, and philosophical story that is something more than just another vampire horror.