MY NEIGHBOR TOTORO. Real anime treasure

Hayao Miyazaki is the Japanese creator of childhood dreams. The animations produced by Studio Ghibli are classics that have influenced generations of Japanese children. The character Totoro, featured in the studio’s third film, enjoys such popularity among children in the Land of the Rising Sun that it’s akin to Winnie the Pooh’s popularity in the UK. Miyazaki’s creation, My Neighbor Totoro, unexpectedly became his flagship production, elevating him to the heights of Japanese animation artistry. Just like his fictional character, he became an icon of children’s cinema, crafting worlds of untouched, pristine nature and friendly spirits, drawing inspiration from Japanese traditions while finding magic in ordinary reality.

Animation is big business in Japan, and Studio Ghibli is its national treasure. Seven works from the studio have made it onto the list of the 15 highest-grossing anime productions, with the film Princess Mononoke from 1997 surpassing Titanic in popularity in its home country. It’s no wonder that Miyazaki, who oversees the best animations in the country, is practically worshipped. He’s often compared to Walt Disney, even though the American visionary was more of a producer, while the Japanese artist rolled up his sleeves and personally hand-painted his films. This is the secret to his works because Miyazaki’s films are primarily visually enchanting. Subdued, subtle color palettes, effortless realism, and meticulous attention to every smallest detail are some of his hallmarks.

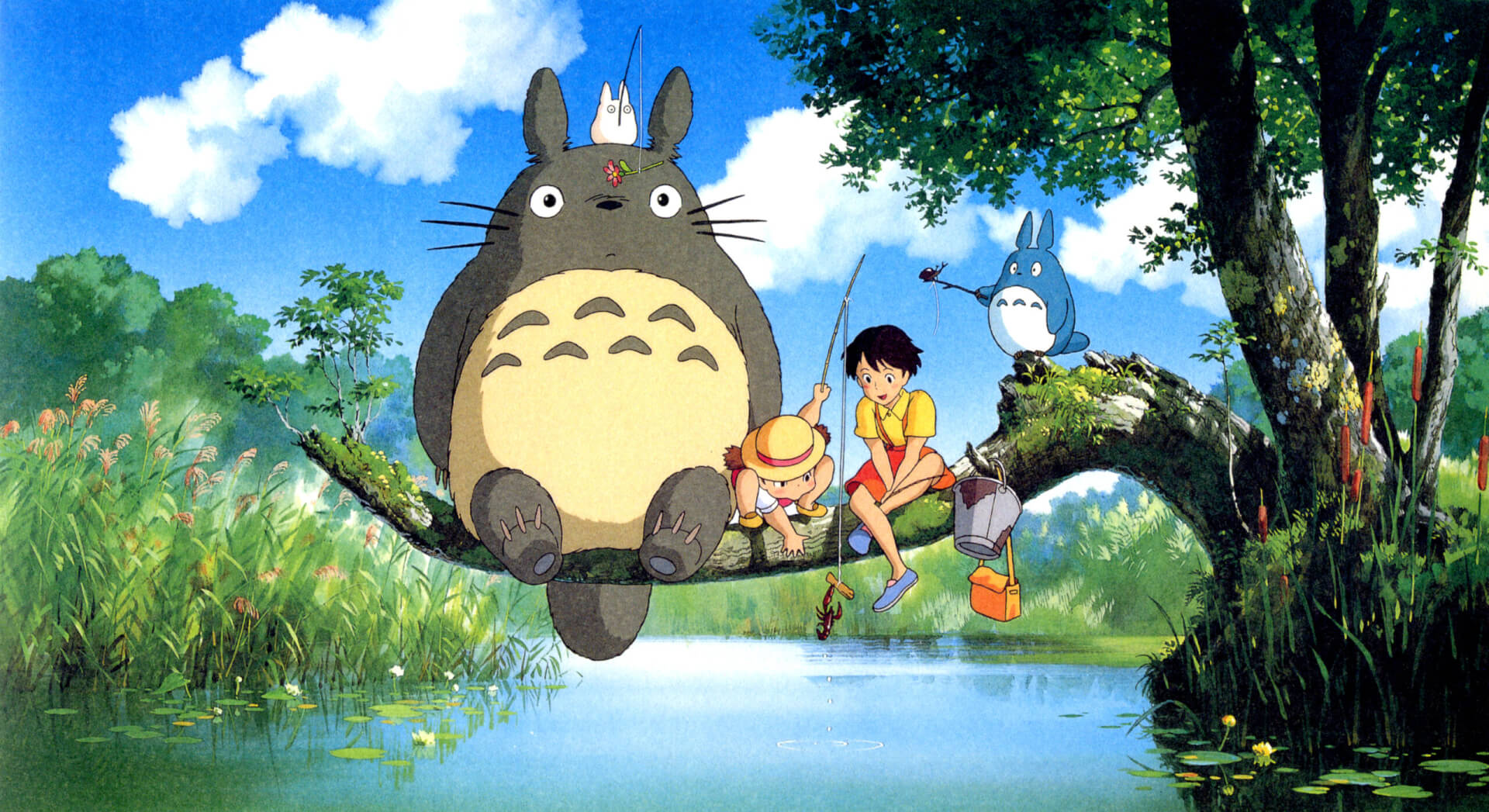

On April 16, 1988, Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies premiered, as did Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro. These two very different films, one solemn and the other warm and idyllic, would soon leave a significant mark on Japanese cinema. Unlike the first film, which tells the story of the tragedy of war, the second one is set in post-war rural Japan. The film opens with the scenic countryside of the satoyama – a mosaic of rice fields, dense forests, meadows, ponds, and streams. Nature, in all its intricacy, is alongside the two main characters of the film, sisters Mei and Satsuki, the most important element of the story, shamelessly flowing into almost every frame. Every plant, flower, stream, and the bottle resting at its bottom is an integral part of the realistic world depicted.

The sisters, along with their father, move to a secluded village, where they are waiting for their mother, who is in the hospital, to return. As they familiarize themselves with the new environment, they carefully explore every nook of the unfamiliar area. They stroll along well-trodden paths adorned with statues of Jizō, the guardian of children, the weak, and travelers. Their father takes them to a Shintō shrine located on a hill at the foot of a massive divine camphor tree. According to their father, Professor Kusakabe, this tree “remembers the old days when people and trees were friends.” The characters thus greet the spirits of the forest and ask for their protection. Magical forest creatures, including the titular Totoro, are said to inhabit this sacred tree and will soon become friends with their new neighbors.

Is Totoro, a huge, white-gray, fluffy creature with black claws and a wide smile, who perches on tree branches at night, a spirit of the forest? According to the director himself:

Totoro is not a spirit. I believe it is a creature that feeds on acorns. I suppose it’s just a forest watcher.

Totoro and other creatures, including soot sprites, only reveal themselves to the main protagonists. They provide comfort in the absence of their mother, alleviating fear and longing. Totoro takes Mei and Satsuki on a journey to an alternate reality, which is the wild and uncharted nature—a representative of order, harmony, and innocent childlike carefreeness. While My Neighbor Totoro distinctly outlines the relationship between humans and the gods and spirits of nature, the question of who Totoro is to the protagonists—a magical being, a spirit, or a creation of their own imagination—remains unanswered.

My Neighbor Totoro primarily tells the story of the strong connection between humans and untouched nature, drawing heavily from the traditional Shintō religion of Japan. The central objects of worship in this faith are kami—spirits, essences, deities, ranging from the sun goddess Amaterasu to lesser entities like Inari, the kami of prosperity, whose roadside statue makes an appearance in the film. The term “kami” also refers to individual divinities, the sacred essence dwelling within a rock, tree, river, animal, or even a person. Kami and humans are not separate; they exist in the same world and share in the complexity of the universe.

Why not consider that Totoro himself is a kami, a revered spirit of the camphor tree? He inhabits the sacred tree bound with Shimenawa ropes to protect it from malevolent spirits. He also accelerates the growth of trees through dance and stands guard over the forest. With Totoro as a Shintō spirit, one can establish a connection through quiet and profound contemplation of the beauty of nature, just as young Mei does upon arriving in the countryside. Furthermore, only Mei and Satsuki can see Totoro because they are the most human, pure-hearted beings. Shintoism teaches that only in the purest hearts and most open minds, a state called “kokoro,” can one interact with kami. The friendship between the forest creature and the sisters becomes a complete unification of humans and nature.

Like other works by Miyazaki, My Neighbor Totoro is characterized by its utopian portrayal of the harmonious coexistence of humans and nature. The director creates worlds drawing heavily from traditional Japanese animistic beliefs, as well as crafting adorable creatures that inhabit treetops and dark corners of abandoned houses. The film’s world is sealed off from the rest of the world by a tall camphor tree wall, remaining a pristine and idyllic paradise where every element of nature is alive, overseen by fluffy beings. Miyazaki’s enriching fantasy is filled with sentiment and spiritual solace. His sun-warmed story exudes unparalleled lightness, charm, and childlike magic.

The perfect medium for the stories of the legendary director becomes classical Japanese animation. The remarkable skill of Studio Ghibli’s animators, who approach the beauty of nature with extraordinary sensitivity, is revealed in the form of detailed depictions of the natural world. The animators illustrated the fantastic and peculiar world of supernatural creatures with remarkable precision and delicacy. Every aspect of the landscape appears to possess its own spirituality. The animation’s meticulous artistry, featuring precise drawings and a harmoniously coordinated subdued color palette along with watercolor backgrounds, contributes to the film’s serene visual composition.

Although My Neighbor Totoro was a box office failure more than 30 years ago, attracting only a small number of viewers to theaters, the film has rightfully gained recognition over time, paving the way for its creator, Hayao Miyazaki, to success. Since then, the titular character has been regarded as the most important figure in children’s animation. It evokes the secrets of nature and the beauty of childish imagination. The forest creature has become not only a pop culture icon but also the most important mascot for young Japanese children. In 2013, Totoro firmly established itself in the realm of nature when a newly discovered species of velvet worm in Vietnam, a worm-like creature with numerous legs, was named Eoperipatus totoro, due to its resemblance to the red Catbus from My Neighbor Totoro.