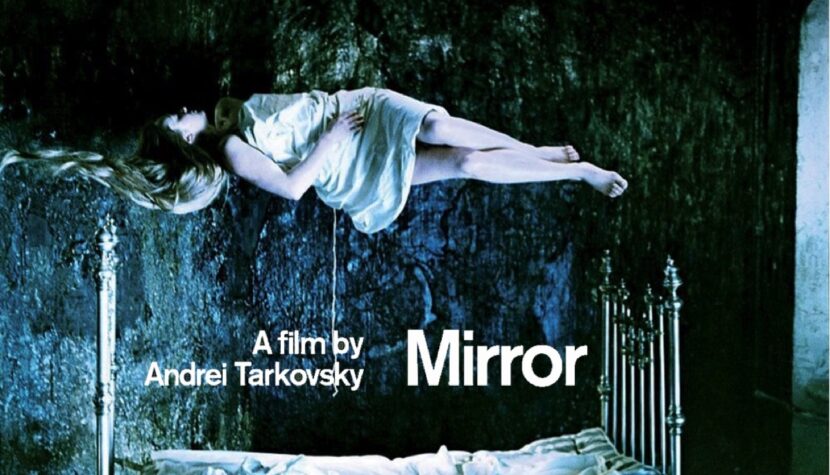

MIRROR. Prohibitive and Uninviting, Yet a Masterpiece Nonetheless

Each one is a piece of a larger whole and contains clues essential for interpreting the others. Each of them says something important about the creator himself and metaphorically shows what the director either does not want or cannot express directly. The depth of the Russian’s films owes much to this personal perspective. Among all his works, Mirror stands out as the most personal and one of the most important.

When Tarkovsky worked on Mirror, he was already a fully formed artist. He had developed his own unique language through which he communicated with the audience. The key to understanding the film seems to be the first scene, where the line I can speak freely is uttered—just as ambiguous as the rest of the film, but clearly indicating that this time the director does not intend to hide behind someone else’s story and that this film is about him, his loved ones, and the events that shaped him.

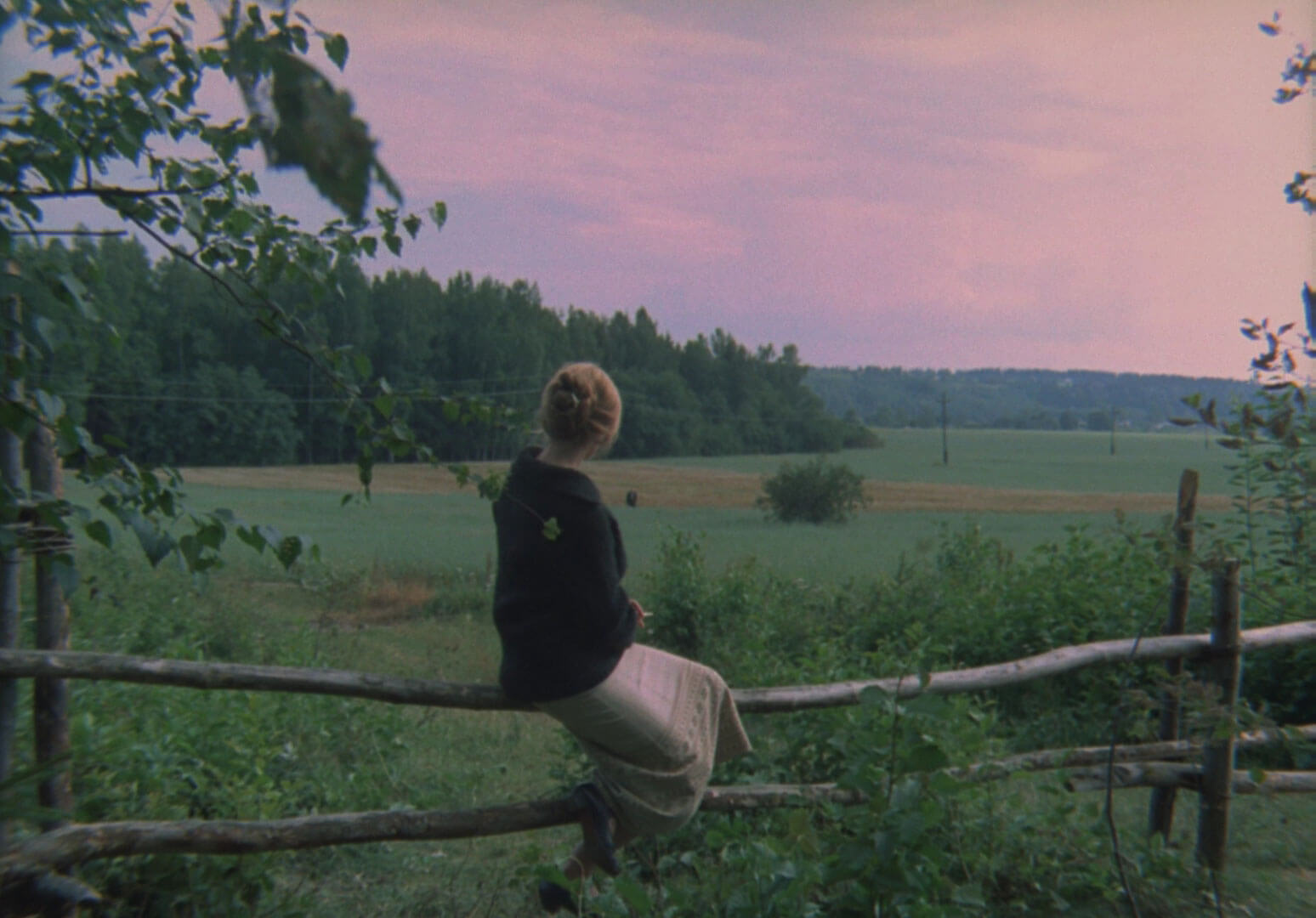

Regarding Mirror, it is difficult to speak of a plot, although it cannot be said that the film is entirely devoid of one. The action unfolds on several planes simultaneously—the alternating use of color and black-and-white film seems to suggest which plane we are dealing with at any given moment. Both characters played by Margarita Terekhova (mother, Natalia) have a son played by Ignat Daniltsev (Ignat, Alexei). One can infer that despite the different circumstances in which they find themselves, for Tarkovsky, they represent the same person or, alternatively, embody the same archetype.

It is hard to say whether the director meant the archetype of the mother or the wife. It is possible that he meant both—this seems to be suggested by the scene in which Terekhova, looking in the mirror, sees the face of an older woman. Later, this woman turns out to be Ignat’s grandmother—played by Larisa Tarkovskaya herself. The Soviet director had previously invited family members to appear in his films (his first wife, Irma Raush, played Ivan’s mother in Ivan’s Childhood), but this was the first time that the woman, believed to be the prototype of the film’s central character, actually appeared on screen. This clue cannot be ignored when attempting to interpret Mirror.

To appreciate the multi-layered nature of “Mirror,” one must know a bit about Tarkovsky’s biography and at least some of his films…

Explaining all the references and metaphors is practically impossible, and moreover, like any great creator, Tarkovsky leaves enough ambiguity in his work for everyone to interpret it from their own perspective, so this film will mean something different to each viewer.

It is worth mentioning that compared to Tarkovsky’s earlier films, Mirror is a much more polished work. The framing, lighting, and editing are all perfectly balanced; it is clear that nothing in this film was left to chance. It is evident that the director spent a lot of time explaining the roles to the actors, which, combined with Terekhova’s incredible talent, resulted in a performance that can be considered the best in the Russian’s entire filmography. Terekhova is excellent—there is not a trace of artificiality or exaggeration in her performance, which was somewhat irritating in Tarkovsky’s earlier films. It is also hard to find weak points in the supporting cast—the standout here is Anatoly Solonitsyn, one of Tarkovsky’s most frequently appearing actors.

When Mirror was being made, Tarkovsky already had a solid position. He had secured his place in history with Andrei Rublev, so during the making of Mirror, he could afford much more than he could at the time of his debut. Moreover, his earlier successes undoubtedly emboldened him. The result is stunning—Tarkovsky’s fourth full-length film is a masterpiece in every respect.

Words by Michal Bleja