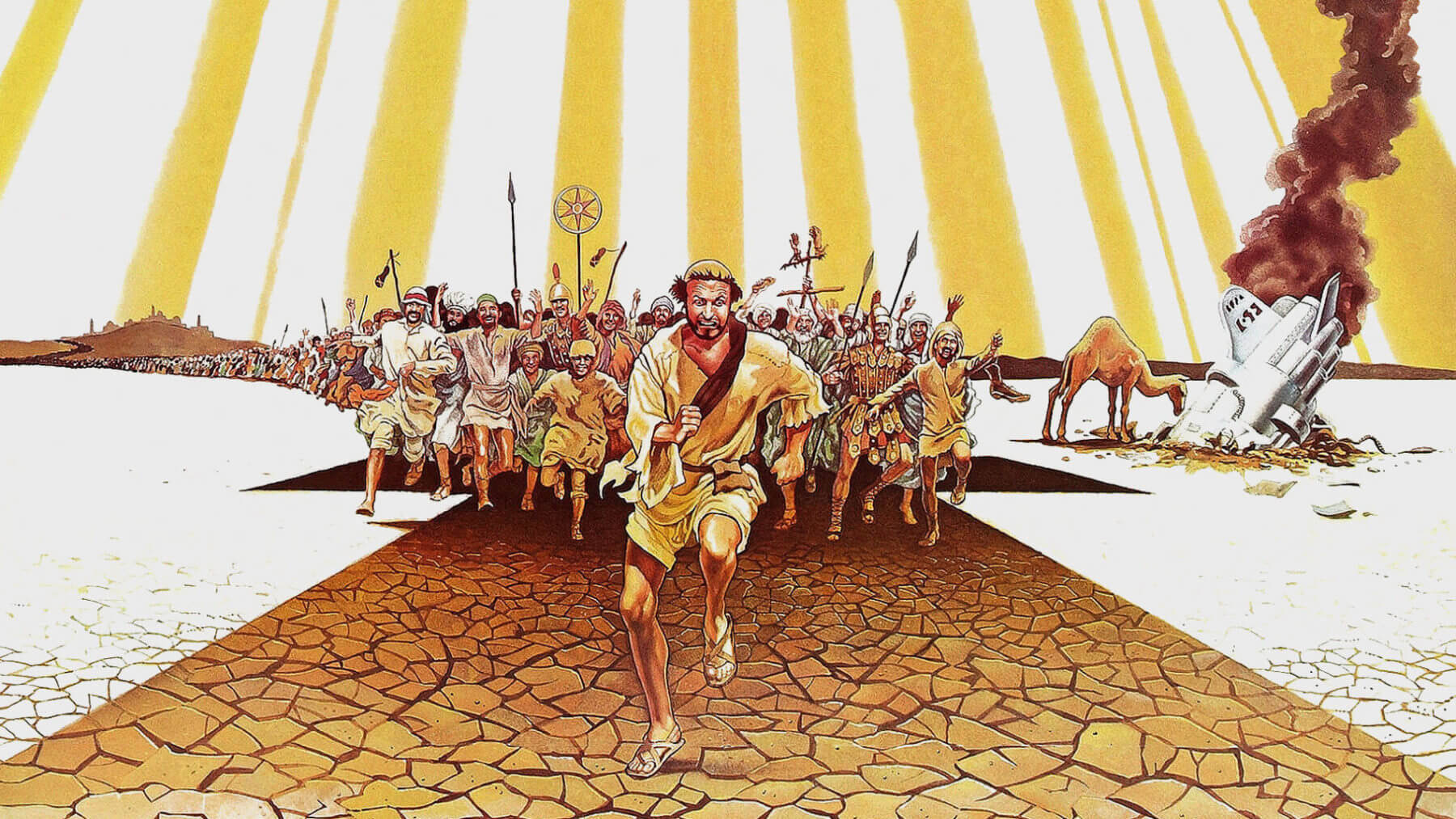

LIFE OF BRIAN. Monty Python’s hilarious masterpiece

The legendary comedy group of the seventies took over British television, creating the marvelous Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

These six men quickly achieved celebrity status both on the islands and across the ocean, allowing them to break out of the square frames of the television sets of the time and embark on larger, much more expensive projects. Apart from And Now for Something Completely Different, which was essentially a re-shot collection of the best sketches from the series, the first full-length feature film made by members of Monty Python was Monty Python and the Holy Grail. However, it was only a few years later that five Brits and one American (let’s not forget about Terry Gilliam!) managed to turn the world upside down with their controversial second feature-length project – Life of Brian.

Not everyone knows that this wonderful film almost never saw the light of day. The project was financed by EMI Studios – they provided the Pythons with all the equipment, part of the crew, and money for the trip (the exteriors were supposed to be shot in Tunisia). A few days before the departure and the start of the shooting period, the studio unexpectedly withdrew from the investment. The reason was very simple – the CEO, Bernie Delfont, finally read the script, which he found cheeky, blasphemous, and rather unfunny.

The Pythons found themselves in a tight spot. Without financial backing, with canceled flights, and a script that systematically deterred potential benefactors. Ultimately, the project was saved by one of the world’s biggest Monty Python fans – George Harrison. The musician, and privately a friend of Eric Idle’s, who personally asked him for help in this matter, established HandMade Films specifically for the needs of Life of Brian. In the future, Harrison’s company produced films such as Time Bandits by Terry Gilliam and Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels.

Soon, more problems began to arise on the horizon, fortunately of a slightly smaller caliber. The previous film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, was co-directed by Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones. During the production of Life of Brian, it turned out that both gentlemen had two completely different artistic visions. In his autobiography titled Gilliamesque, A Pre-posthumous Autobiography, Gilliam recalls:

Of the handful of scenes I eventually directed – one of them being the arrival of the three kings to the village – I tried to give it an epic scope. I don’t think there was anything wrong with the way Terry was doing it; it’s just that he was doing everything as if it were for television. As a result, there were scenes – especially the one with Pilate, for which we built a ridiculously rich set with a straight Roman room inside a three-story Jewish house, actually invisible on the screen – where, in my opinion, we lost important, impressive shots.

And indeed, it is hard to find in Life of Brian the epic scope that was a common feature of many historical-religious, Hollywood epics of the 1950s and 1960s such as Ben-Hur, Quo Vadis, The Ten Commandments, or King of Kings. This is probably because Gilliam eventually gave up, leaving Jones free rein, and settled for a few minor roles and the position of production manager. Later in his autobiography, the American adds:

In hindsight, however, I see that no matter how much I stamped my artistic feet and argued how it could be improved, Life of Brian not only got made but turned out rather splendidly. In moments of sanity, I even admit that the end result strikes a pretty good balance between my lofty ambition and baroque angles and Terry J’s more practical sensibilities.

The next minor problem was related to the actor playing the title role. The Pythons struggled for a long time to decide which of them should play the unfortunate Brian. John Cleese was particularly eager to play this role, as he had never before (apart from a small film parodying Sherlock Holmes adventures – The Strange Case of the End of Civilization as We Know It) had the opportunity to play the main character appearing in almost every scene of the film. Ultimately, through lengthy discussions and democratic voting, it was decided that Cleese would be much funnier in minor roles, and Graham Chapman should play Brian.

The choice turned out to be a bull’s eye. Graham Chapman played the role of his life, creating an unforgettable character on the screen – a lost, somewhat “thrown into life” Brian, who is successively met with further misfortunes. However, the Pythons’ decision was very risky – Chapman was struggling with a serious alcohol problem at the time. His then-partner, David Sherlock, recalls that the comedian could drink two or even three bottles of gin a day. Complications related to Chapman’s alcoholism affected his colleagues during the work on The Holy Grail. Graham was then notorious for getting drunk at night and mixing up lines during the day, as well as rebelling against the decisions of the directing duo, which consisted of his close friends. Before starting work on another feature film, the Briton decided to quit alcohol and organized a private rehabilitation, which had a very positive effect on his acting performance.

Life of Brian caused an incredibly huge stir around the world even before its official premiere, which took place on August 17, 1979, in New York. Protests were organized to prevent the Python’s film from seeing the light of day. Demonstrations marched through the streets, with Catholics, Jews, and Protestants, priests, rabbis, and pastors marching arm in arm – almost everyone felt offended, although in reality, nobody had seen Life of Brian. “It takes a lot to bring these people together, and we did it in a very simple way – by offending them all at once. An article covering these protests was published in Variety, and each religion got a couple of columns to admit that what we did was inappropriate, which everyone agreed on. It was awesome,” recalls Terry Gilliam in his book. Leading the protests in the UK, in the homeland of most of the Pythons, was Mary Whitehouse, the head of the influential organization Nationwide Festival of Light. It was mainly thanks to her relentless efforts and the written pressure of thousands of her supporters that the premiere of Life of Brian was blocked in Swansea, Whitehaven, Harrogate, and Cornwall, among others. Interestingly, the controversial film could not be seen in any cinema in Norway either. Norwegian fans of Monty Python had to travel to Sweden for screenings! The situation seemed so comic and absurd to the creators of the Flying Circus that they quickly turned it into a perfect joke and started promoting the film in Scandinavia as “so funny that it was banned in Norway.”

I had the incredible luck to watch Life of Brian for the first time in a cinema two years ago. To experience this incredible British humor, these fantastic sketches (stoning, stuttering Pilate, Biggus Dickus, the completely unexpected flight of the aliens, the only right suicide squad, or finally the iconic song sung in the last scene of the film by Eric Idle) in the company of dozens of strangers, in a dark room and on a big screen – a unique, absolutely priceless experience.

A few days ago, for the purpose of writing this text, I refreshed Life of Brian on the couch in front of the TV. The second viewing brought me a lot of joy (despite the fact that I remembered almost all the jokes) and made me realize how wrong the opponents of this film were in 1979 and how wrong they are today, calling it blasphemous. The only group that should feel offended after watching the Pythons’ film are neither Catholics (to whom the author also belongs), nor Jews, nor Protestants, nor Muslims. They are the dimwits without their own opinion, the numskulls blindly following the crowd, who could successfully compete for the title of “aristocratic fool of the year” hand in hand with the five mentally challenged participants of the famous sketch. It is the thoughtless who laugh in Life of Brian – Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin, and we have been laughing with them for forty five years.