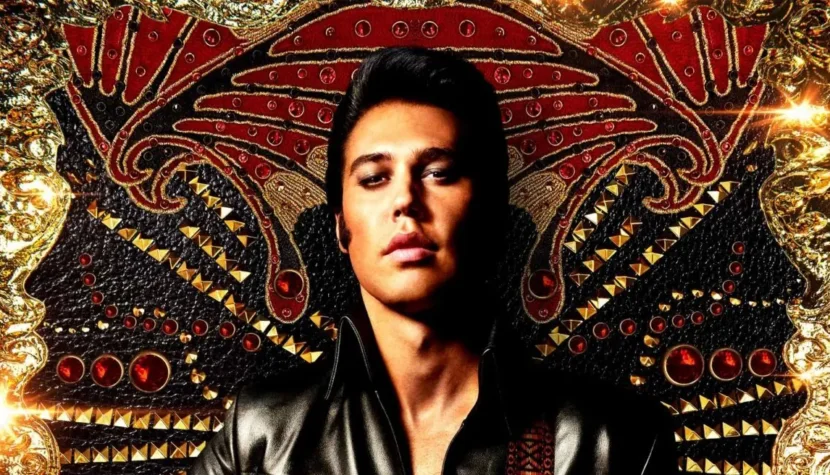

ELVIS. Everything for Sale [REVIEW]

In the early parts of Baz Luhrmann’s “Elvis”, the film touches on themes close to those in Miloš Forman’s “Amadeus”. Though it’s more of a variation, don’t take this comparison too literally. On one side, we have Presley (Austin Butler): a musical genius, a phenomenal stage personality, but only on a local level. A contract with a studio, but only a regional one. Popularity, but still on a small scale. On the other side stands his manager, Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), who knows nothing about music but has an extraordinary knack for business. Artistic value means little if it can’t be sold profitably. Parker can see this, he’s determined, cunning, and never gives up. He’ll strike while the iron’s hot.

Mozart remains Mozart. Meanwhile, Luhrmann’s Salieri diverges and takes a slightly different path. In the end, he reaches a similar point, but without the fuel of anger and jealousy. What entices Parker is the rustle of banknotes and signing new contracts. Seeing wonders isn’t always a gift.

If the intricate aesthetic of “The Great Gatsby” resonated with you, then “Elvis” might deliver another revelation. The rainbow colors, the saturation of hues in costumes, cars, and interiors elevate Luhrmann’s film. The music video style – cut, cut, cut, divided, tripled, quadrupled screens – never disorients. Instead, it allows the intensity of the experience and all the sensory stimuli to come through in a condensed way: the glow of the lights, the euphoria of the audience, Elvis’s twisted figure, fingers dancing over the guitar strings. You’ll feel it.

As is typical of Luhrmann, the camera is constantly in motion, always somewhere new. At one point, it’s a frog’s perspective; at another, a bird’s-eye view. But there isn’t a hint of editing chaos or narrative confusion. The formal richness is part of a precisely measured plan, and the visual flamboyance is a perfect lure to hold our attention. There’s extravagance, but never too much. The aesthetic of kitsch and the excess of staging are organic tools for Baz Luhrmann. It’s his natural creative environment. It’s hard to refuse when the director of “Romeo + Juliet” sends such an invitation once again.

A Living Legend

As much as the visual elements impress, “Elvis” stumbles somewhat in terms of drama and seems overly superficial. It also suffers from a common problem in biopics. We follow Elvis’s career from his youthful fascination with gospel to his final breaths. It’s a story about everything, but only a little bit of everything. The love between Elvis and Priscilla never reaches a boiling point, family quarrels are mentioned out of obligation, and his military service feels almost anecdotal. Do Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy’s assassinations flash across TV screens? Yes, because they’re meant to be important, because it’s great American history that’s supposed to serve the plot in some way.

Elvis only seems truly exhausted and consumed when he’s performing. Luhrmann pours most of his energy and directorial passion into what happens on and behind the stage. It’s where the characters’ stances crystallize, and their views sharpen. Conflicts heat up to a boil, and the characters express themselves most clearly. Elvis in the spotlight is the most genuine and trustworthy. That’s also the Elvis you pay the most for.

It’s possible the creators are fully aware that Elvis Presley long ago transformed into a global cultural symbol, and reinforcing that image is the right move, presenting him as a continuously living legend. His private life becomes fable, and his stage persona becomes an icon, a sign of the times. I get the sense that in “Elvis”, Baz Luhrmann stops at the packaging and doesn’t try to scratch away the layer of gold. Nevertheless, it’s the director himself who remains the biggest star of “Elvis”. His unmatched sense of staging, compositional bravery, aesthetic sweetness, and belief in camp as a stylistic elevation are remarkable. Beautiful things. Baz Luhrmann has certainly earned his place in the Museum of Cinema.