THE WHITE RIBBON Explained. Restraining Mr. Hyde

These days, it’s fashionable to laugh at Freud. Packs of students, a considerable number of columnists, and crowds of journalists with ironic smiles reference his theories only to drag out a few theses concerning the surprisingly significant role of human sexuality.

Where there’s the word “sex,” there are soon flushed cheeks, darting eyes, and grimaces that, though trying to create the illusion of seriousness, betray the internal state of a given speaker. And so, Freud, chewed up by the gigantic machine of pop culture, has become the dirty old man who sees everything through a sexual lens. Certainly, the spectacular misuses of his theories helped this along, particularly in “film studies” analyses. The tower as a phallic symbol in Casablanca, or seeing the same symbol in Count Orlok’s bald head in Murnau’s Nosferatu, must provoke a smile of pity. Nevertheless, we shouldn’t forget that Freud didn’t only write about reproductive organs; he observed something that, for years, we’ve tried to deny. With both hands, my left leg, and my right elbow, I sign under his theory of defense mechanisms. I also agree that within each of us lies a more or less repulsive Mr. Hyde, waiting for an opportunity to embark on a night-time escapade. In part, I agree that culture is a source of suffering for Hyde and the most refined defense of our facade—if we stick to the metaphor, let’s say, of Dr. Jekyll. I also agree with Michael Haneke, who—as we’ve come to expect—proves in a subversive way that Freud’s equation concerning culture can be written in reverse. The White Ribbon demonstrates that culture can act as a catalyst, unleashing our inner demons.

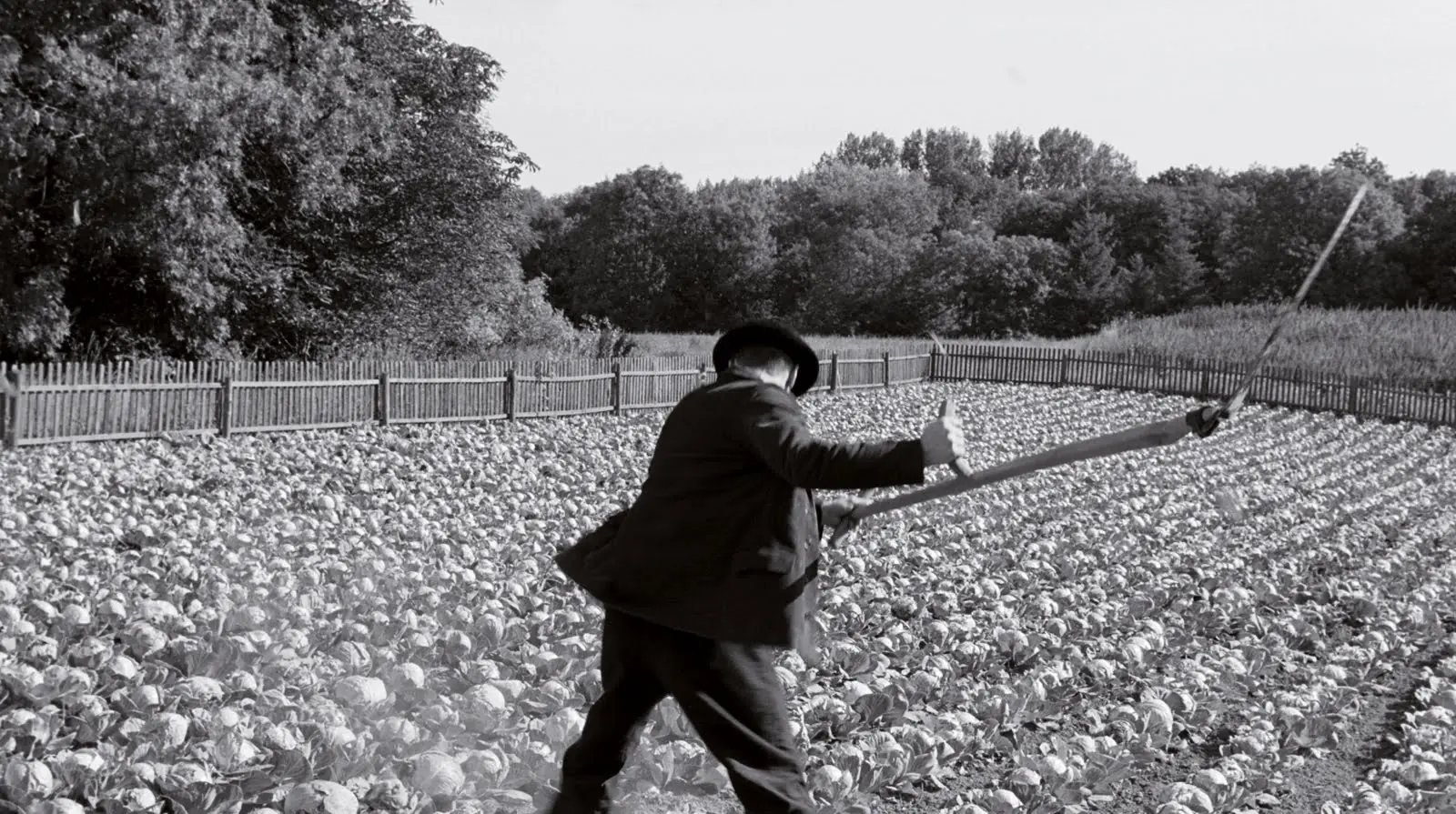

What other culture, if not the deeply rigorous, classically understood Protestant culture of the early 20th century, could keep Hyde in check? Theoretically, it should be the very one to protect a person from themselves most completely. The practical aspect of this hypothesis is demonstrated to us by Haneke on the celluloid strip of The White Ribbon, which transports the viewer to the world of a small, German, Protestant village in the second decade of the 20th century. The muted blacks, whites, and grays of the depicted world deceive the viewer, who simply has no reason to anticipate any misfortune beyond what we commonly call an “unfortunate accident.”

However, barely visible but devilishly resilient strings don’t tie themselves around trees in such a way as to block the path the local doctor takes while riding his horse. Since the ropes tied around the trees aren’t what we call an “unfortunate accident,” neither can the series of severe fractures and internal injuries suffered due to the sudden halt of the gallop caused by the horse’s fall be considered accidents. Premeditation worked here, the will to do evil. And where did this happen? In a village where the so-called Word of God is the law, and where growing boys are tied to their beds so as not to give in to their youthful urges at night.

And what of those muted colors, calm shots, static scenes during which we demand to see at least a small trace of editing? All this is just a mask, bringing to mind the opening scene of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet—on the surface, we have red poppies, green grass, and snow-white fences surrounding idyllic gardens, but a bit closer to the ground (where the mask begins to peel) lies the vermin, Hyde resides there. This childishly simple but reluctantly revealed principle, demonstrated by Lynch, fits perfectly with the universe of Haneke’s The White Ribbon. Observing a series of “inexplicable” acts of aggression in a peaceful area, we witness the breaking of the seams of the carefully sewn cultural costume—a convention created by the villagers, according to which everyone follows the word of God and despises anything that even vaguely connotes sin or scandal.

The convention they (the villagers) adopted bears the marks of Freudian sublimation, that is, the transfer of life energy from this “bad” place (sexual urges, desire for aggression and domination) to another sphere of life (blind obedience to strict rules of faith, fanatically suppressing any interest in sexuality, punishing deviations from the rigid code). And maybe all of this would work if “culture were not a source of suffering,” but this kind of culture is an unbearable source of suffering for Hyde, so he takes the only logical step—he escapes on a “night-time escapade,” though the cobbled streets of London are missing.

It’s not just Hyde prowling the town—the perpetrator(s), whose identity I won’t reveal, though it’s not the most important point of The White Ribbon. In fact, every house has its “little demon” manifesting during corporal punishment inflicted on supposedly “disobedient” children, if being late is a disobedience worthy of a beating. It manifests during the humiliation and harm done to those who should be particularly close to us.

It manifests, finally—what should be paradoxical—during the supposed following of the “word of God,” which, in the performance of the depicted community, often resembles more a variation on the Code of Hammurabi. The conclusion is simple—such a strict culture doesn’t suppress the actions of our darker side, but quite the opposite, it causes it to “swell” and explode uncontrollably, allowing us to return to normalcy, that is, a consensus between the “bad” and the “good” (however naive that may sound). To release bad emotions, scapegoats are needed—the more defenseless, the better, because they won’t fight back.

Haneke demonstrates exactly this kind of mechanism, and the key—at least for me—to understanding his vision is the recurring motif of the white ribbon, meant to remind children to maintain the purity of their souls, and one of the final scenes in which the director insistently (from different distances) shows us the large, “cold” church building looming over the town. What is the purpose of ribbons tied to the arms of people who have themselves forgotten to follow the rules they are meant to symbolize?

Apropos of “buildings,” Nietzsche once said: Since you believe in God who sits in Heaven, why do you cover the sky above your heads, kneel, and direct your gaze to the ground? Without the strict laws dictated from the pulpit, would society have organized life in this way? What’s more, Haneke takes it a step further, provoking thought by setting the events before the outbreak of World War I. Is it possible that the pattern which worked in a small Protestant community could also work on a larger, European scale? Could World War I have been, for Haneke, such an “escape of Hyde,” an exploding safety valve, the ruptured seam of the tight corset of 19th-century culture?

Many questions remain, far more than answers obtained. The identity of the perpetrator(s) in The White Ribbon takes a backseat. Returning to the questions themselves—their main feature is likely that posing them in general discourse (i.e., intended for a broad audience) will certainly be fruitless. In general discourse, they will be rhetorical questions. Only for the individual viewer can they become a reason to reflect, first on themselves, and also on what is happening and has happened around them. Thus, Haneke tells us something about himself, but also motivates us to try to look at ourselves…