THE SHELTERING SKY. Bertolucci’s Visually Stunning Opus Deciphered

One of these filmmakers is the Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci, whose work significantly transcends traditional trends and conventions. The author of The Spider’s Stratagem skillfully uses cinematic techniques.

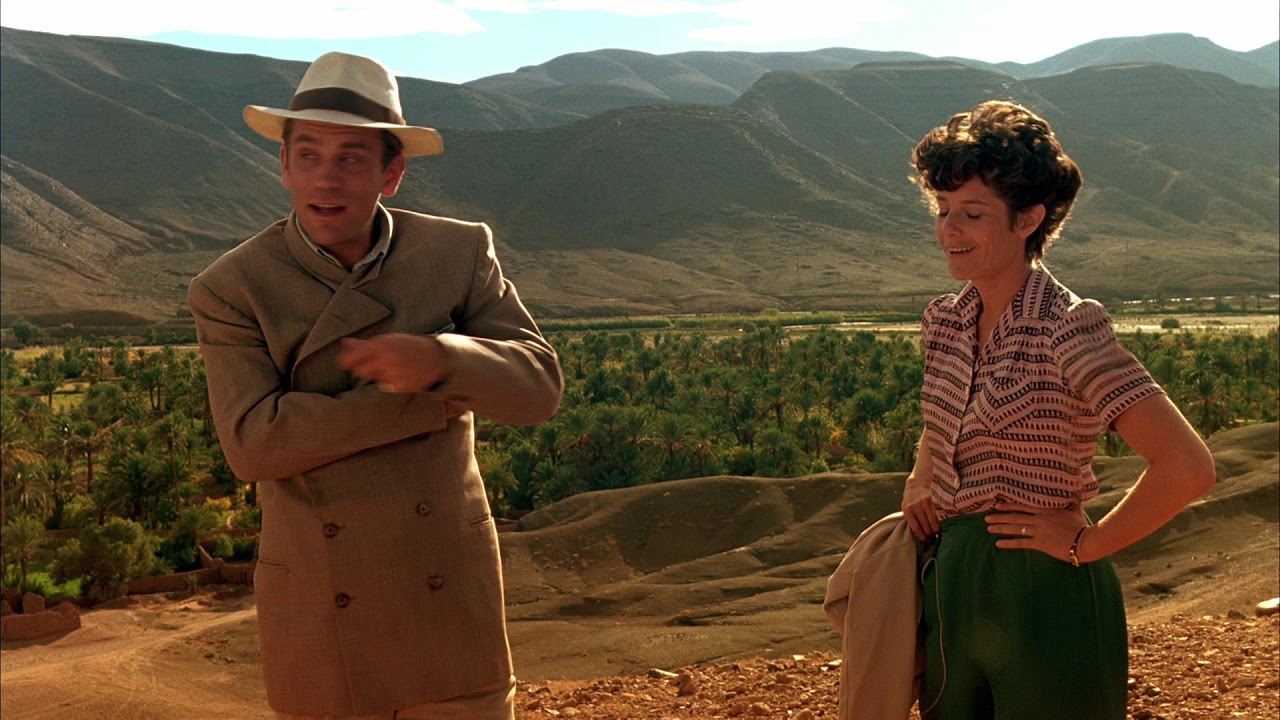

The Sheltering Sky (1990) tells the story of the married couple Kit and Port Moresby, who are experiencing an emotional crisis. Along with their friend George Tunner, they decide to escape from the big city to Africa. They believe that there, they might prevent the ultimate breakdown of their relationship. As a result, we get a portrait of people disillusioned with life, lonely, and uncertain of their feelings. The film is based on the novel by American poet, novelist, and composer Paul Bowles, who debuted in 1949 with The Sheltering Sky. The roles of the three protagonists are played by John Malkovich, Debra Winger, and Campbell Scott.

The documentary opening of The Sheltering Sky shows a panorama of the city by day and night, in different seasons. New York in the 1940s glimmers with thousands of lights. Many buildings are shown from a low-angle perspective, making them appear even larger and grander. Modern architecture and means of transport, neon lights, street bustle, residents engaged in daily routines, elegant businessmen, sophisticated women, and bustling entertainment centers are elements that convey the specific atmosphere of this place. This characteristic mood is further enhanced by the soundtrack, composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto. A shot of a departing ship heralds significant changes for the film’s characters. The “swinging” New York is left behind. A “new” world awaits. But what is it really?

Bertolucci’s film is reminiscent of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Here, too, the journey can be viewed on the level of the protagonists’ introspection – a dive into their minds. Following this thread, The Sheltering Sky becomes a story about the tangled fates of individuals. Additionally, an initiation mechanism is activated. The protagonists abandon civilization and enter a completely different reality. Time ceases to have any meaning for them. Permanent changes occur in their psyche. The director clearly emphasizes the moment of transition. After the initial sequence, depicting a portrait of New York, there is a cut to a close-up of Port’s face, visibly exhausted from the long sea voyage. This scene is accompanied by Arabic, exotic music. The transatlantic journey can be seen as a threshold situation – a suspension between civilized America and the Black Continent. The three protagonists then disembark in the Maghreb. They see an old, rusty crane. This image evokes contemplation, reminding of the transience of all material things, and evokes the past. Exotic music intermingles with classical, somewhat sentimental pieces.

In the next scene, Kit opens a suitcase and reaches for a hat. Inside are books. Among them is Nightwood – a novel by American writer Djuna Barnes, a representative of Anglo-American literary modernism in the 1930s and 1940s. This scene provides viewers with information about Kit herself – her tastes and beliefs. Meanwhile, Tunner takes souvenir photos. A group of African children, summoned by Port, takes the suitcases and they all head to the city. Only from the conversation between the couple and a customs officer do we learn who the characters are – Port is a composer, Kit a playwright, and Turner a “vain businessman”.

In one city street scene, a poster promoting the film Sans lendemain (1939) by French director and playwright Max Ophüls catches the viewer’s attention. It is no coincidence that Bertolucci chose this particular filmmaker and this work. Ophüls used cinematic expression with great precision. He was fascinated by fluid camera movements, zoom-ins, and zoom-outs. He emphasized symbolism and emotional tension between characters. The similarities between the French filmmaker and the director of The Sheltering Sky seem quite apparent. The title of Ophüls’ film – No Tomorrow – clearly resonates with the message of Bertolucci’s work.

The next shot of The Sheltering Sky: an old man’s face, the camera zooms in – we see almost the entire interior of a colonial-style restaurant where the protagonists sit. Along the walls hang mirrors – this motif will reappear later in the film. Besides the trio of friends, other tourists sit at dusty tables. Children in ragged clothes shine the shoes of guests from faraway America. A boy sells the daily press. We hear a cheerful French song. An illusion of happiness is created; a desire to experience an unforgettable adventure. In the background, we see Paul Bowles, the author of the novel. In reality, he alone knows the future of the created characters.

Moreover, we do not know who the mysterious woman in a hat, who enters the restaurant, is. Perhaps she appears in the film under the same principles as Paul Bowles – she is a sort of intermediary between two worlds – literary and cinematic. The couple lights a cigarette, and we see close-ups of their faces. In this shot, Kit resembles a femme fatale from film noir. Her beauty, intelligence, emotional ambiguity, and self-confidence do not go unnoticed by George. The pair flirts with each other. Port, against his wife’s wishes, begins to recount his fatalistic dream. The irritated woman leaves. The protagonist tries to explain Kit’s behavior, stating that for her, everything can be a bad omen: a white Mercedes cannot just be a white Mercedes, a sign carries meaning and symbolism. These words can be translated into the realm of film art. Every element of the film image is a carrier of meanings, an unlimited field for interpretative performances.

In the next shot, we see the Grand Hotel from the outside with its rich ornamentation, wrought-iron balconies, and stained glass at the door. Moments later, we are in the married couple’s bedroom (or rather bedrooms). The protagonists talk to each other while lying on beds. They sleep separately in two connected rooms. One shot is particularly poignant: on the right side, behind open doors, we see Port lying in bed. This place (and the protagonist himself) is bathed in orange light.

As Patti Bellantoni writes, the use of such color in the film can indicate several interpretative paths: firstly, the vibrant orange in the interiors as a product of romanticism; on the other hand, it can take us on a subconscious journey, broadening the field of emotional experiences. Orange can also simply be perceived as exotic. On the left, we see Kit’s reflection in the mirror. Such an arrangement proves that the relationship between these two is only a facade, an illusion. The mannerist prop of the mirror, similar to a costume or mask, indirectly and exaggeratedly depicts reality. The breakdown of the marital relationship is inevitable. They are additionally separated by physical objects (suitcases, furniture, knick-knacks). We see partial reflections of the characters. It seems that the journey to Africa will not bring the expected result. On the contrary, it will reveal what has been deeply hidden so far. Human instincts, hidden desires will come to light. Port will find a semblance of happiness in the arms of a prostitute. Kit will be seduced by a dark-skinned native.

Bertolucci does not hide his interest in the psychoanalytic concept of man and the realm of self-awareness. The concept of apperception is linked to the aforementioned idea of initiation – a sort of rebirth, discovery of one’s self, reconciliation with fate. The director focuses primarily on these aspects.

The existential message of The Sheltering Sky is evidenced, among other things, by the character of Paul Bowles, who comments on the protagonists’ actions from off-screen. The writer points out the thoughtlessness, inevitability of fate, and helplessness in the face of passing time. This way, an additional level of narration is built.

The relentlessness of destiny is particularly evident in the character of Port. The first sequence of the film shows Mr. Moresby’s exhausted, sweat-soaked face. As a result, Port dies of malaria. Earlier, he confesses his sincerest love to his wife – discovered too late, however.

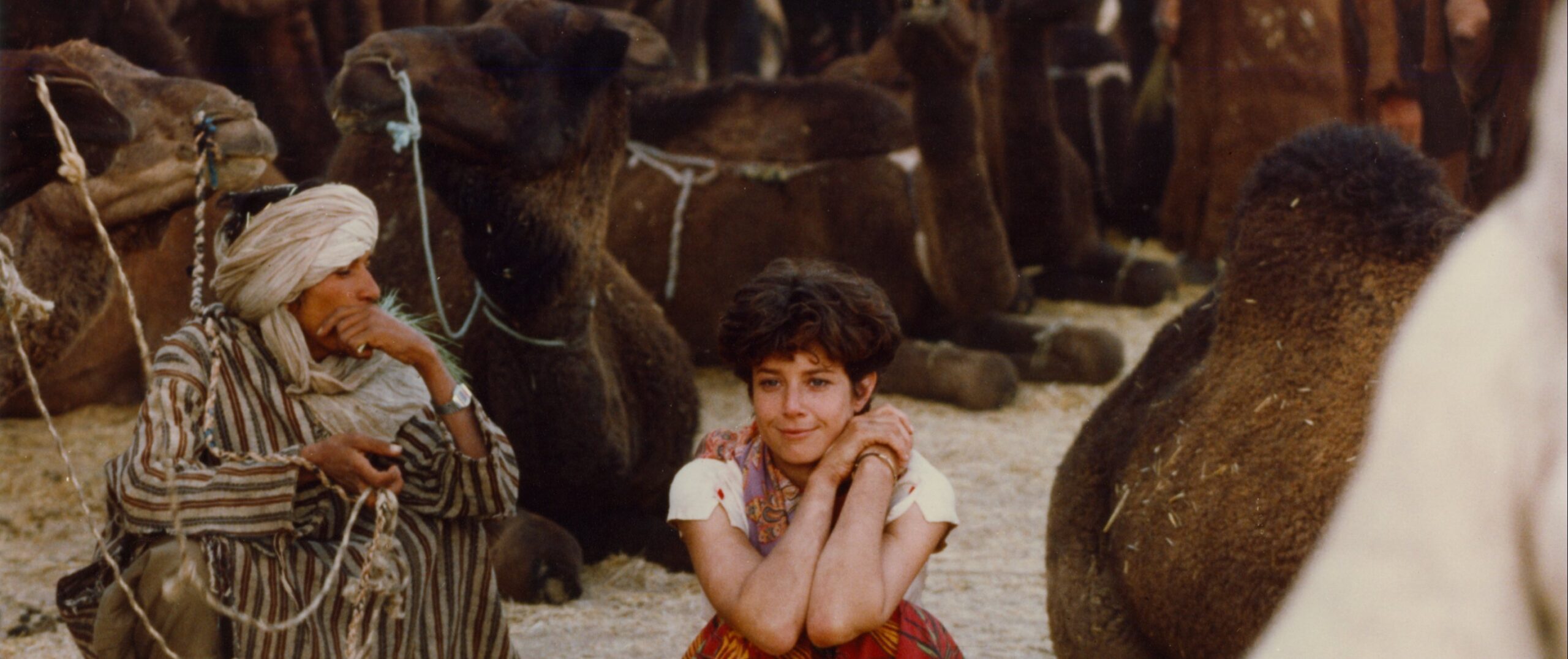

Kit, on the other hand, is an exceptionally strong and spiritual woman, willing to submit to the whims of fate. As if she wanted to see what the consequences would be. She undergoes a transformation and forgets about what was. In a sense of meaninglessness and emptiness, she joins a Tuareg harem. She appears deranged. She does not take the opportunity to return to America. In the final scene, she disappears into the crowd on the streets of Tangier.

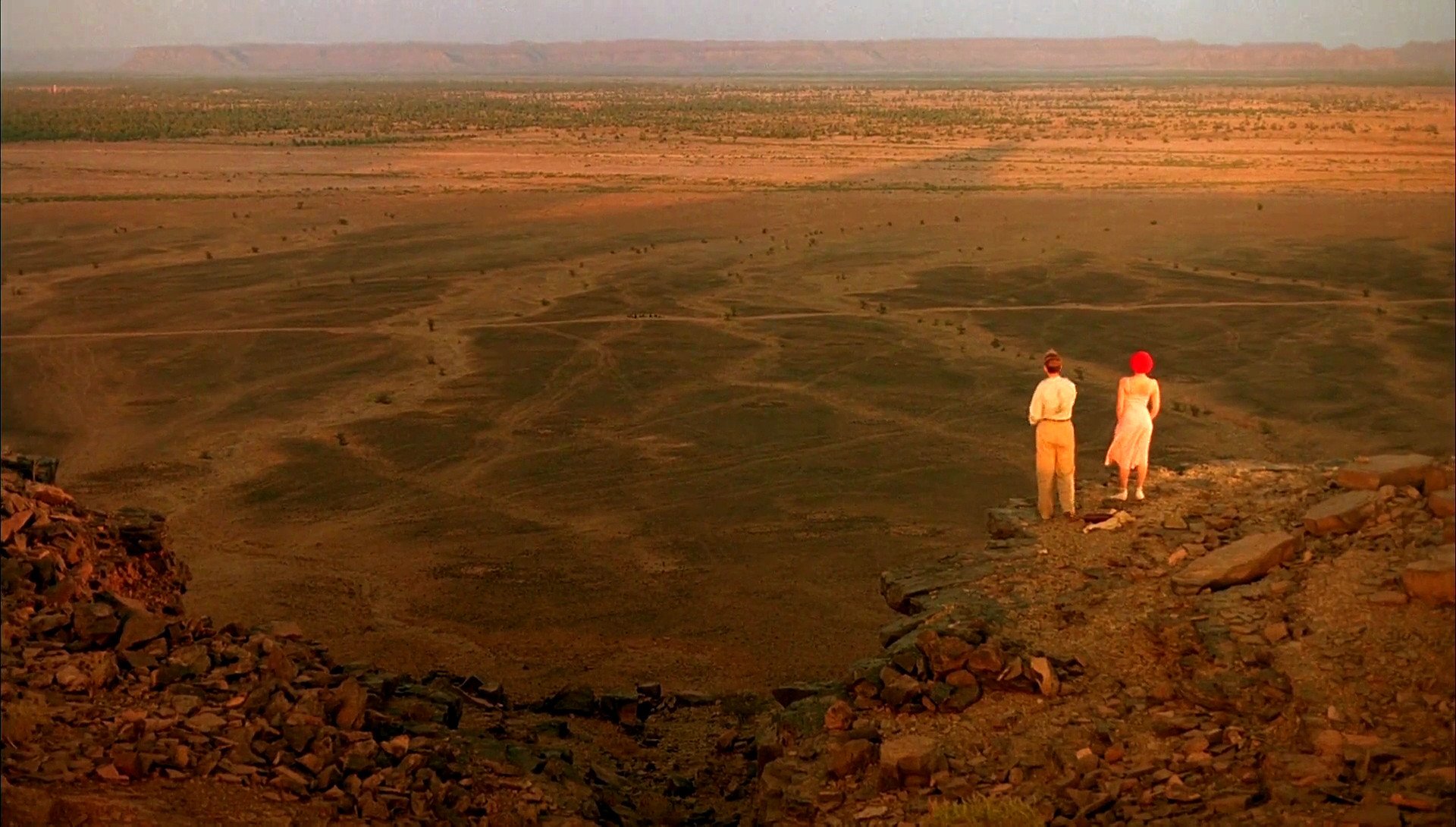

In The Sheltering Sky Bertolucci embodies the concept of man “thrown into existence.” In collaboration with cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, he visualizes the idea of the protagonists’ loneliness in picturesque, melancholic images of the desert. The sense of alienation corresponds with the ethnic groups presented on screen. Hostile glances, incomprehensible rituals, unfriendly living conditions evoke a strong sense of alienation. Bertolucci and Storaro’s exoticism does not at all associate with sunny beaches or luxury hotels. The creators depict a world that would make a person reflect on themselves.

The Sheltering Sky is a film presenting timeless content. The director’s intention was to make the audience aware that each of us can be “thrown into existence,” regardless of time, space, or social position. The slow pace of the action recreates the atmosphere of life in the deserted areas of Morocco and other North African countries. The lack of adaptation and harshness of life are evident in the austerity of the landscape, and the vast sky deepens the sense of nothingness.

After the scene of entering African soil, Kit, Port, and George discuss the difference between a tourist and a traveler. The heroine explains that a tourist thinks about returning home from the moment they arrive. A traveler doesn’t know if they will ever return. Based on this single statement, Bertolucci directly suggests the philosophical and existential undertones of the film. The visual layer is intended to help the audience with interpretation and provoke reflection. The cinematic means employed are not only to highlight the ambiguity of human nature but, above all, to underscore the absurdity of existence – we may think we are free, yet we are still burdened by our past and acquired experiences.

Written by Martyna Suchon