SAW Explained: The Real Killers Behind John Kramer’s Jigsaw

He preferred to carry out his mission under his own name – John Kramer. However, the results proved to be just as questionable as the sincerity of the mission’s foundation itself. Jigsaw’s declarations do not entirely align with his actual motivations, even if he is not fully aware of this or, more likely, refuses to admit it to himself.

Kramer of Saw Series fits the typology of a self-appointed vigilante, driven by a belief in the mission he is carrying out (mission-oriented). His manifesto centers on making people who carelessly and thoughtlessly squander their lives realize the magnitude of their mistake. In Jigsaw’s view, life is a gift that must not be wasted—a gift so precious that the fight to preserve it justifies absolutely everything. However, people lack the will to fight, they lack the survival instinct. Kramer, therefore, organizes games based on what he perceives as an individual’s weakness, testing their desire to survive and thus delivering a lesson for the future (of course, only for those who manage to adhere to the rules – and there aren’t many of them).

Technically speaking, Jigsaw is not a murderer – at least not in the sense of directly taking his victims’ lives. After all, that would conflict with his pompous philosophy. He is a proponent of autonomous choices—or so he claims. Whether you survive or perish, the choice is yours, and any failure is entirely your fault.

In 2006, a young man from Nova Scotia, Stephen Marshall, was searching for a significant life mission—and he found one. He spent considerable time gathering information about registered sex offenders in Maine. From a list of thirty-four names, he selected twenty-nine and diligently compiled the necessary details to “teach them a lesson.” He then traveled to Houlton to visit his father, borrowed a truck and a firearm, and proceeded to target the first two individuals on his list. In Milo, he shot and killed 57-year-old Joseph Gray, and in Corinth, 24-year-old William Elliott. By all indications, he planned to eliminate all twenty-nine people on his list. However, the police intercepted him on a bus en route to his next target. Marshall had no intention of being taken alive and committed suicide, thereby abandoning his mission in its infancy.

As a curious aside, another Stephen Marshall, a 38-year-old Briton from Hertfordshire, was dubbed “The Jigsaw Killer” by the press. However, this title has no spiritual connection to John Kramer; instead, it refers to a literal “jigsaw.” Marshall had a habit of dismembering his victims and leaving fragments of their bodies in different locations. The total number of his victims remains unknown—he was convicted of a single murder, that of Jeffrey Howe, and refused to provide further details.

Michael Mullen had a difficult and painful childhood. Abused both physically and sexually, he grew into a deeply troubled and unstable individual, haunted by an obsessive desire for revenge. The vengeance was not directed at his own abusers, but at those who could harm other children and condemn them to a fate similar to his own. The catalyst for his actions was the case of Joseph Edward Duncan III, a particularly depraved pedophile and murderer. In a four-page letter sent to the Times, Mullen explained that he hoped to die before Duncan so that he could “welcome him to hell.” This twisted sense of justice and retribution motivated Mullen to take matters into his own hands, targeting those he deemed a threat to children, even if it meant resorting to extreme violence.

In the meantime, posing as an FBI agent, Mullen knocked on the door of a house shared by three registered sex offenders: Hank Eisses, who had served less than six years for raping a 13-year-old; Victor Vazquez; and James Russell. According to Mullen’s own interpretation, he gave each man a chance to survive. Only Russell managed to pass the “test,” as he showed genuine remorse for his actions. The other two, Eisses and Vazquez, allegedly “boasted” about their crimes and shifted all the blame onto their victims. As a result, Mullen spared Russell’s life but killed Eisses and Vazquez. This act of violence, in Mullen’s eyes, was a form of justice against those he believed to be unrepentant threats to society. I am not a saint, Mullen wrote. I am not proud of taking two lives, and I’d gladly give up my own, but that would mean nothing. He added that abused children often become part of a vicious cycle of violence, growing into addicts, alcoholics, or even pedophiles themselves. Mullen died in prison in 2007 under unclear circumstances.

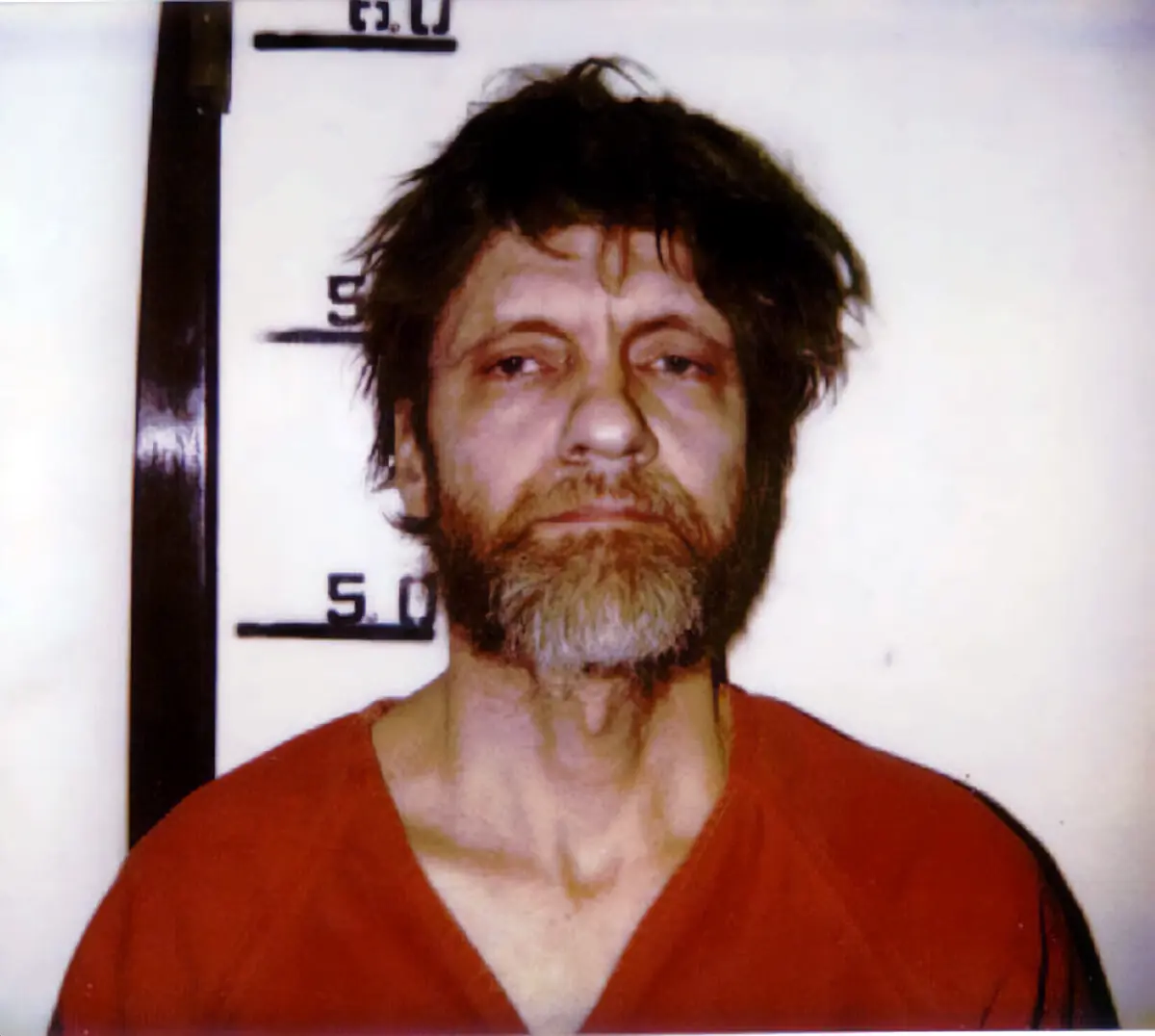

The pair of vigilantes mentioned above, like Kramer, were driven by a desire to eradicate corruption and repair societal flaws. Show remorse—and you live. One of the most famous mission-driven killers was Ted Kaczynski, who went down in criminology history as the Unabomber. Of Polish descent, the son of Wanda (née Dombek) and Theodore Richard Kaczynski, he was a child prodigy and mathematical genius. Between 1978 and 1995, he conducted a terror campaign, planting or mailing homemade bombs to individuals he considered champions of new technologies.

In Kaczynski’s view—a survivalist who lived off the grid in a cabin without running water or electricity—technological progress was humanity’s greatest enemy, dulling the natural instincts essential for survival. Over his years of activity, the Unabomber killed three people and injured twenty-three. Apparently frustrated with the FBI’s slow progress, he sent a manifesto—over 50 pages and 35,000 words—to The New York Times, demanding its publication and promising to end his terrorism if this condition was met.

The manifesto titled Industrial Society and Its Future was eventually published, after long debates, by The New York Times and The Washington Post. The style of the essay was later recognized by Kaczynski’s brother, David, and his sister-in-law, Linda. At the time of his arrest in April 1996, the Unabomber held the record for the most costly investigation in FBI history. A forensic expert diagnosed Kaczynski with paranoid schizophrenia, which he himself considered an “idiotic” and “politically motivated” diagnosis. Ultimately, he avoided the death penalty, but although there is no chance of him ever being released, he remains steadfast in his beliefs, publicly advocating for the inalienable right to freedom of speech, and maintains an active correspondence with over four hundred people.

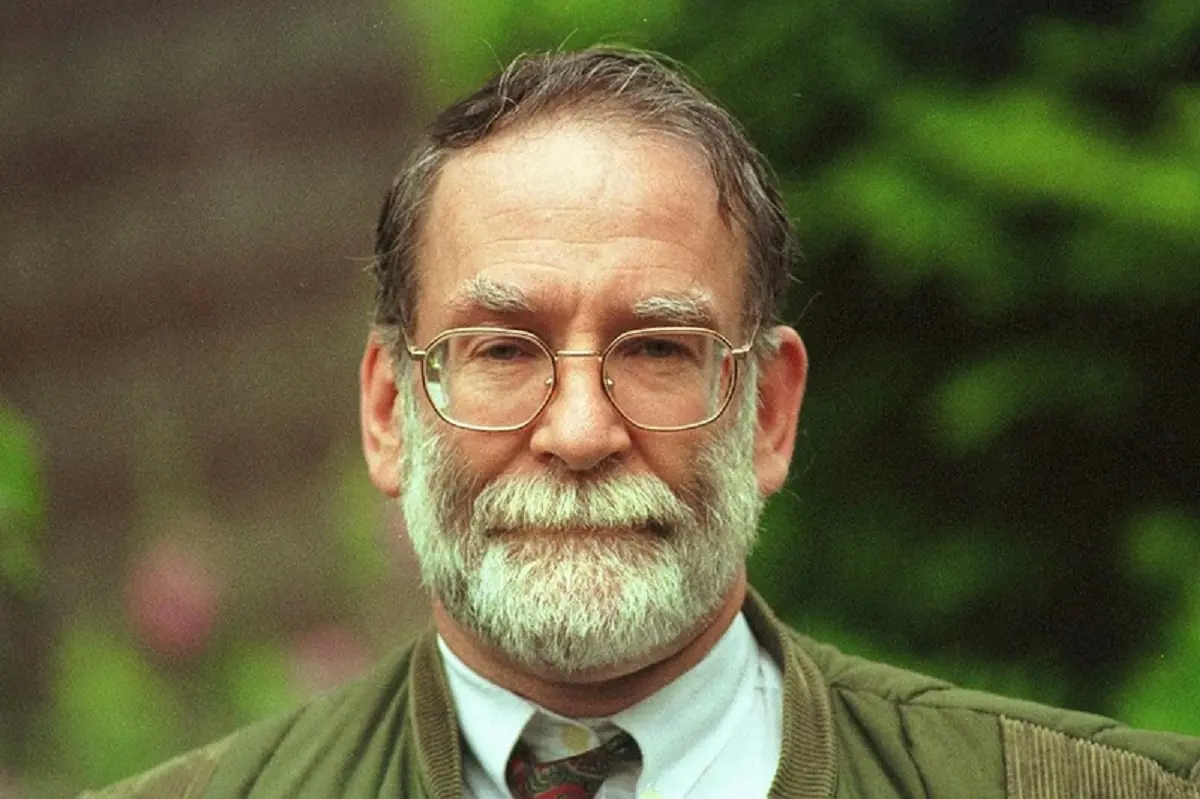

And speaking of killers with a mission, it’s impossible not to mention the one who claimed the most victims: Harold Shipman, a British doctor known as Dr. Death. While for the Unabomber, killing people was more of a side effect that he was willing to accept but did not actively pursue, Shipman had direct, even intimate, contact with his victims. He was arrested for a total of fifteen murders, tried for four, and is estimated to have been responsible for the deaths of two hundred and eighteen people, if not more. His tragic story began in his early youth when he witnessed the terrible suffering of his mother, dying of lung cancer, who only found relief in the powerful doses of morphine she received.

Shipman graduated from medical school in Leeds and then practiced as a general practitioner for several years, until the number of unexpected deaths, especially among elderly women, under his care began to raise concerns among several families. One of them also noticed that a will had been forged. This was Shipman’s biggest mistake, as by making himself the sole beneficiary in the falsified document, he immediately came under suspicion. He acted the same way every time: he would administer a lethal dose of painkillers to his patients, write down the cause of death as natural causes, and beforehand would intentionally describe the patient’s health condition as much worse than it actually was. Because he was highly respected, he usually had no trouble convincing grieving families to have their deceased loved ones cremated.

His defense, which tried to convince the judge that Shipman was a compassionate angel of mercy, failed completely, as none of his fifteen victims were in an advanced stage of illness. Did Shipman believe he was helping them? One can only speculate, as he never admitted guilt, and in 2004 he hanged himself in prison. Perhaps what started as a mission he believed to be a legitimate effort to help the sick eventually turned into an addiction to control and power, especially since Shipman had a tendency to develop addictions and enjoyed indulging in drug-induced highs. Let us remember this evolution of his actions (or rather, its degeneration), as it will be important later.

Robert Christian Hansen, also known as the “Butcher Baker” or alternatively the “Human Hunter,” kidnapped, raped, and murdered at least seventeen women between 1971 and 1983. A skinny stutterer covered in acne scars, Hansen spent most of his teenage years meticulously planning revenge against women who mocked him, or women in general. He entered criminal history through a psychological profile created by Roy Hazelwood, which became famous for its remarkable accuracy. Hazelwood not only predicted that the offender was an experienced hunter with an inferiority complex, but also suggested that he was likely a stutterer and collected souvenirs from his “victims.”

I mention Robert Hansen here for one basic reason: his method of operation. Hansen had the habit of releasing disoriented, naked women into the forest and then chasing them down, hunting them like animals. He followed a set of rules that made sense only to him. Some women were given a head start. Others were wounded with a knife before being released. Some were shot from a distance, while others had their throats slit up close. Still, others were set free. It was never fully defined how much of his behavior was related to the actions of the women themselves and how much was merely a random variation in the game, simply for his own amusement, to avoid repetition. This, however, is another example of a killer who plays a game by his own delusional rules, fulfilling his desire for control while being unable to manage his own life.

John, just before transforming into Jigsaw, found himself in a situation similar to many of his later victims. Professionally, he was a civil engineer. His once-happy, successful marriage to Jill falls apart when she is attacked and, as a result, miscarries. John, growing angrier and more indifferent with each passing day, distances himself from Jill, leading to their eventual divorce. The man responsible for this tragedy, one Cecil Adams, would later become Kramer’s first target. This same Kramer would later subject Jeff Denlon to “forgiveness tests” and accuse Dr. Lynn Denlon of neglecting her family after the tragic death of their son in an accident.

After his divorce and the breakdown of his life, John receives the final blow—a diagnosis revealing an inoperable brain tumor. Devastated, he attempts suicide by driving his car off a cliff. However, his body, incapable of defeating cancer cells, still has enough strength to survive the crash. Like many failed suicides, John experiences a rebirth, a newfound appreciation for life and the world. He adopts a philosophy of “enjoying every second” (which is why the element of time is so crucial in his games) and decides to dedicate the rest of his earthly existence to a mission of converting people who have forgotten the preciousness of life.

Kramer uses intricate devices that function like traps, but they can be escaped from, provided the survival instinct is strong enough. Usually, this requires physical pain and psychological sacrifice, often linked to character flaws. These Jigsaw tricks bring to mind the tragic story of Brian Douglas Wells, a pizza delivery man who, with a bomb strapped to his neck, unsuccessfully attempted to complete four tasks outlined in his instructions before the time ran out. The first task on the list was a bank robbery. The footage showing Wells’s head exploding continues to circulate on the internet. This event took place in 2003, a year before the release of Saw. The police investigation suggests that Wells initially took an active part in planning the robbery involving the bomb. He just didn’t know it would be real…

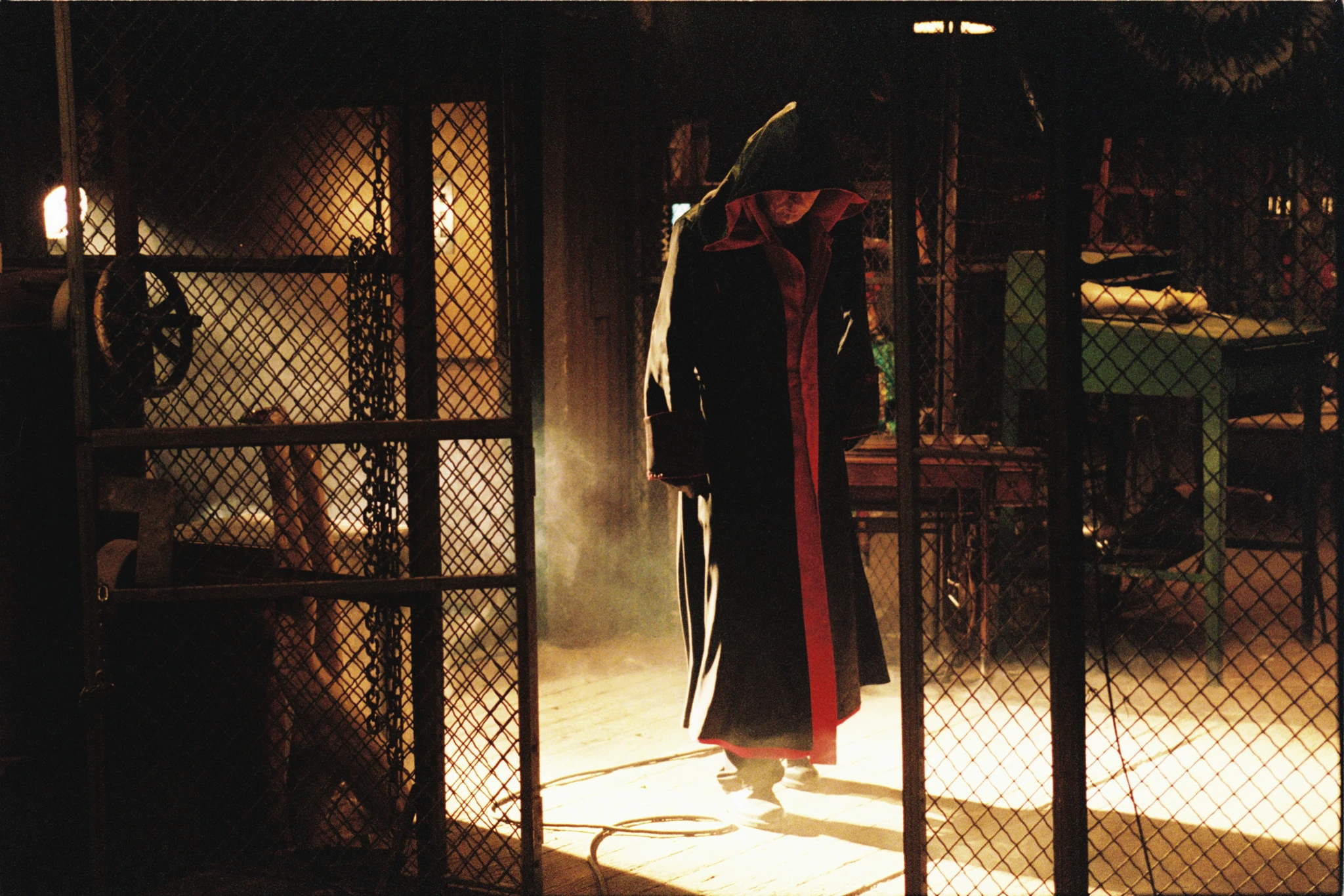

Apart from the traps, another signature element of John Kramer’s modus operandi are the tapes on which he records instructions for his victims. The altered voice, more than an attempt to conceal his identity, serves as a symbolic detachment of Jigsaw from the events. He is an observer and, to some extent, the judge of the outcome, but does not take part in the actual mechanism. First, doing so would distort the purpose of the game. Second, Kramer is keen on not defining himself as a “murderer.” As a messenger and representative, he also uses a puppet, known among fans as “Billy the Puppet.”

The third signature element is the pig mask, worn by Jigsaw and his apprentices during abductions. Kramer began his mission in the Chinese Year of the Pig, which inspired the idea, and the somewhat grotesque appearance of the mask symbolizes decay and disease, both in the world around him and literally in John’s brain. Marking those who failed with a piece of cut skin shaped like a puzzle piece — hence the media nickname — in Kramer’s eyes signifies that the subject is “missing something,” specifically, the will to survive.

John’s philosophy seems incredibly meticulous and well thought out. He himself is an extremely diligent, organized person, focused on the details. He has enough composure and mental resilience to remain still on the floor for hours, playing the role of a corpse — an undeniable feat, even when accounting for the heart-slowing injection and muscle-relaxing drug, which adds to the accomplishment. Kramer is also a highly strategic planner with a backup plan in mind, aided by his ability to accurately judge human character. Charismatic and convincing enough to win the loyalty of successive apprentices, he is aware of their flaws. However, when emotions come into play, as seen with Amanda Young, he struggles to apply his calculated, cold approach, offering his partners — unlike his “objects” — more than one chance to redeem themselves. John also enjoys speaking in symbols, taking pleasure in finding metaphors for his victims’ addictions and character flaws and transforming them into the blueprints for his games.

In the original version of the script for Saw III, there was a scene in which John — realizing on his deathbed that his work had been corrupted, that he would go down in history as a murderer instead of a champion of life and a teacher — breaks down and begins to cry. He realizes he has become someone he never intended to be. While emotionally justifiable — after all, Kramer’s entire concept of victory over disease and death was based on the idea of successors continuing his work — this scene would have been illogical upon closer examination. Why?

Here we come to the greatest manipulation John was able to carry out. He convinced everyone that he separates himself from the actions committed by his victims. At every turn, he emphasizes that not only does he not condone murder, but he also despises murderers. Yet, it is clear that he believes taking someone’s life is entirely justified in the name of survival. Only in this way can Amanda triumph in her test. Ultimately, he also forgives Detective Hoffman, who killed the man responsible for his sister’s death, inspired by Jigsaw’s toys, but by designing a trap that was impossible to escape. John is angry, scolds Hoffman, but in the end, what does he do? He recruits him and places him in the role of his successor. While this is somewhat understandable in the case of Dr. Lawrence Gordon, who found a way to survive without carrying out the murderous scenario — thus becoming Jigsaw’s greatest victory — Hoffman’s selection seems somewhat questionable.

It is likely that John, dazed by the message of his own manifesto, does not fully realize how much the loss of control over his own body and, more generally, over his life, affects him. He seeks a substitute — in the meticulous planning of his games, in his obsessive attachment to rules. However, much like Harold Shipman, at some point he crosses the line between what he declares and what he experiences. John’s victims become an extension of himself. That’s why he wants them to have a chance to survive, why he desires them to fight, because through their struggle, he feels that he himself has not yet lost. He fights through them, feels through them, and most importantly, wins through them. And yes, he wishes them victory — that’s why he is so moved by the fact that Amanda’s traps cannot be disarmed — because, in doing so, she proves to him that survival is possible, achievable even under pressure, even in the worst possible circumstances.

For a moment, he deceives death, which acts like a painkiller. For a brief moment, he again has power and holds all the strings in his hands. The lesson he gives his victims — the lesson of respecting life as their greatest possession — is, in reality, a smokescreen. John is interested only in the moment of struggle and transition, but not in the consequences. He doesn’t give any thought to the quality of the saved life in relation to the price that must be paid for it: the nightmares, the guilt, the recurring physical pain. For John, only he himself matters and the illusion he creates with every winning game.

John Kramer maintains a similarly instrumental relationship with his apprentices. They are needed as extensions of his work, as a means of preserving his immortality. Where it suits him, he turns a blind eye to the rules. Where it benefits him, he invokes their inviolability. He manipulates people like puppets, and to him, they are just another “Billy the Puppet.” His knowledge of psychology ensures the success of this manipulation. He knows exactly which strings to pull to push Detective Eric Matthews to the brink of his endurance. And the fact that, technically speaking, he is still adhering to the true version of events, means nothing. It’s just another trick John uses to justify his actions in his own eyes.

At this late stage of his life, he is not in the best condition. He suffers, is physically frail, and loses strength with each passing day. Therefore, he maximizes his comfort where he can — in the psychological realm. In this regard, he remains strong. Let’s be honest, did Jigsaw really want Jeff to succeed in his test of forgiveness? That smile of John’s at the very end is proof that, perhaps, not so much. Because, in the end, he was once again the master of the game, correctly predicting its conclusion.

As a final curiosity: Matthew Tingling, inspired by a scene from Saw IV, methodically and gradually severed the spinal cord of his roommate, intending to force him to give up his credit card number. He needed money for drugs. One could say that this is a kind of irony. And it would certainly be from Amanda’s perspective.