DEATH BECOMES HER Deciphered. Darkly Grotesque Fairy Tale

Where is my wife?

Your wife is dead. She’s in the morgue.

The morgue?! She’ll be furious!

After his success with the Back to the Future trilogy and the live-action-animation crime spoof Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Robert Zemeckis was hailed as the perfect provider of family entertainment, much like his mentor, Steven Spielberg. So it was quite a surprise for his fans when, in 1992, Zemeckis released Death Becomes Her, a black comedy laced with a touch of macabre humor.

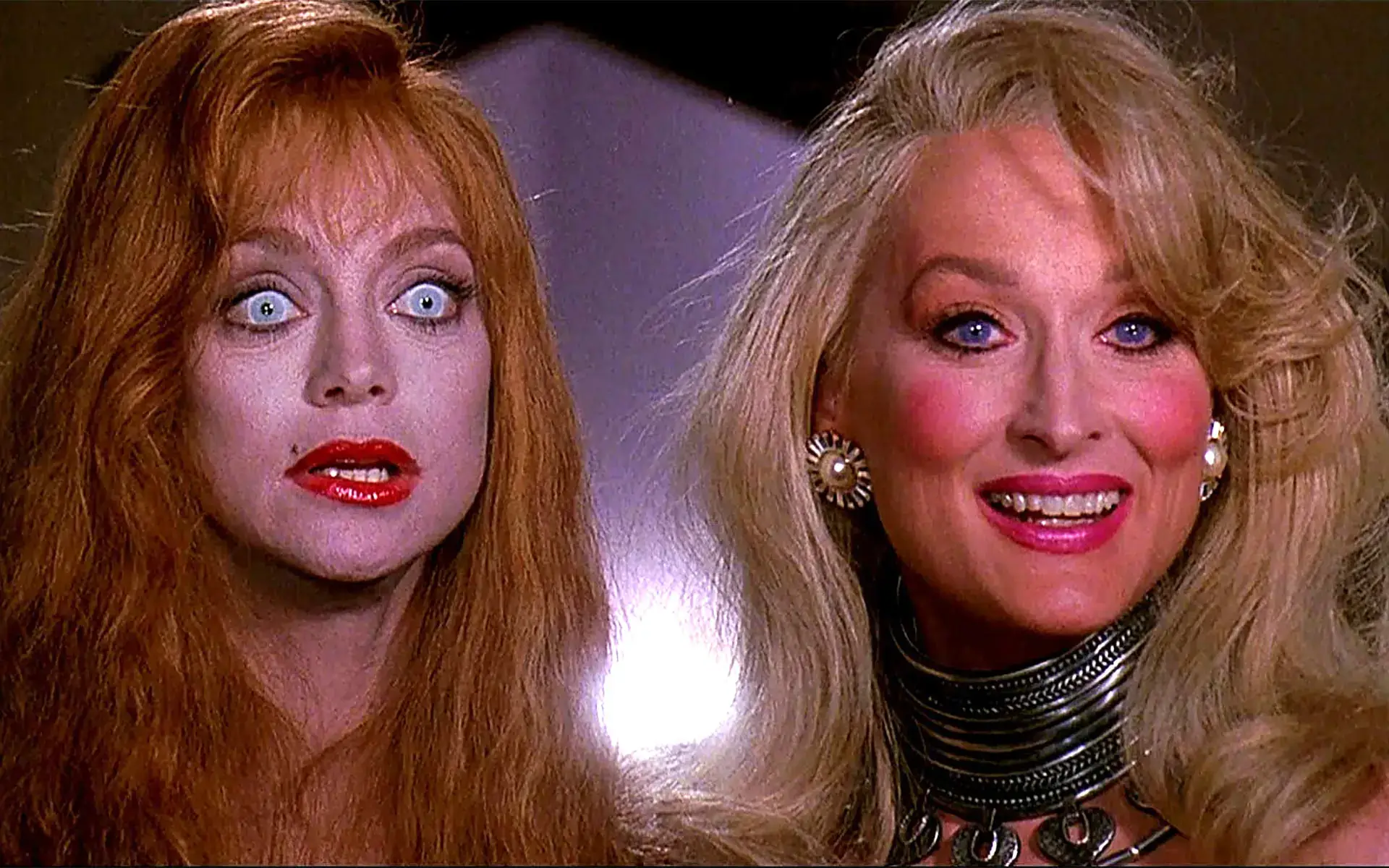

Broadway, 1978. Madeline Ashton (Meryl Streep), the star of the pitiful musical Songbird, feels the relentless march of time weighing on her. Her salvation comes in the form of an acquaintance with Dr. Ernest Menville (Bruce Willis), the fiancé of her friend Helen Sharp (Goldie Hawn). Dr. Menville is a renowned plastic surgeon. This seemingly innocent friendship ends with Madeline marrying the doctor. Heartbroken, Helen plunges into seven years of despair, overeating, and obsessive dreams of ridding herself of her former friend within the walls of a mental institution. Seven more years pass. Madeline Ashton leads a pathetic (if luxurious) life as a faded star, while cheating on her husband at every turn. Poor Ernest, too, has hit rock bottom, abandoning his lucrative practice to make a less-than-prestigious living by painting corpses for funerals.

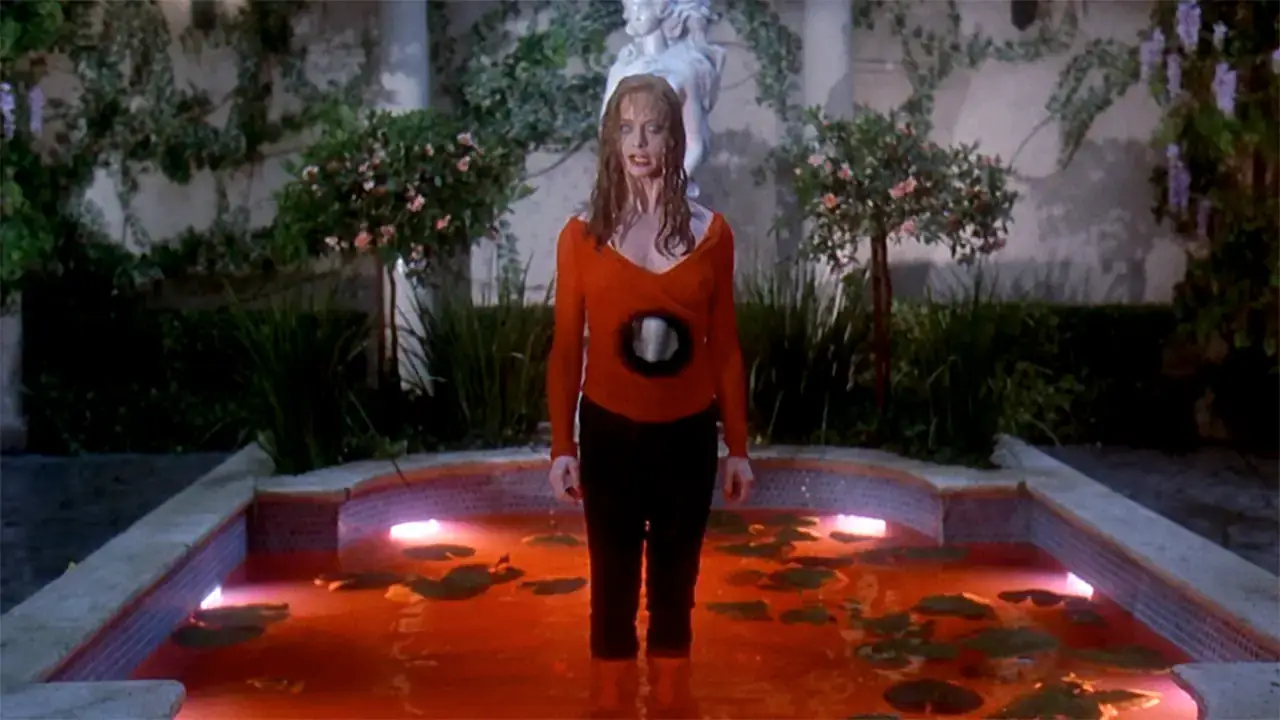

They both eventually encounter a transformed Helen, who, slim and beautiful, is now socially flourishing. Devastated, Madeline, willing to try anything to save her deteriorating looks, ends up at the mansion of the mysterious Lisle Von Rhoman (Isabella Rossellini). From her, Madeline receives a miraculous potion promising eternal youth and beauty. Meanwhile, Helen, still bitter over her past hurts, convinces Ernest to get rid of his wife. A transformed, radiant Madeline eventually mocks her husband’s lack of talent, prompting Ernest to snap and push her down the stairs. Diagnosis: instant death. A panicked Ernest calls Helen, but in the meantime, Madeline—twisted and broken like dry wood—stands up with her head rotated 180 degrees, accusing her husband of his actions.

No one expected a film like this from Zemeckis.

This time, the director used his impeccable technique and sharp storytelling skills to create a biting satire on the upper class, which is plagued by a craze for plastic surgery. The whimsical optimism of Marty McFly’s adventures has been replaced by a cynical dissection of the minds of former Hollywood stars caught in a mutual admiration society. One of the main goals of literature and science fiction is to present contemporary problems in a way no other genre can. By introducing a supernatural element to society’s relentless pursuit of youth and beauty at any cost, Zemeckis created an extremely vivid effect that drifts mercilessly toward absurdity. How to portray the end of a starlet’s legend, mocking her soap-opera style? Just give her hope in the form of a magical elixir that offers an extreme body-lift. Fear not—the starlet will leap at the chance, no matter the consequences. Then, it’s just a matter of sitting back and laughing as we watch her slow downfall.

The miraculous potion offers life at any cost—even beyond death, as the bodies begin to decay. Not even Ernest’s corpse-painting skills can save them, as Madeline’s and Helen’s dead bodies keep moving, unable to comprehend that their time is over. This dark subject is wrapped in a very funny, brilliantly shot, and well-acted package. This effect is amplified by the casting of Isabella Rossellini as the seductive witch. Although she was not exactly young at the time (she was 40 during filming), her timeless beauty and grace almost automatically suggest the surreal possibility that she, too, might have benefited from the potion her character offers.

The all-star cast of Death Becomes Her was assembled against all odds.

Bruce Willis, in the role of Dr. Ernest Menville, gives one of his absolute best performances. Previously known for action-hero roles, Willis plays a timid, henpecked husband with finesse and boldness, trying to find real purpose amidst the pathetic glitz of high society. Meryl Streep, who was mostly known for her serious, Oscar-worthy dramatic roles (which she continues to excel in to this day), suddenly appears in a $55-million Hollywood blockbuster loaded with digital effects. Meanwhile, Goldie Hawn, who built her popular image playing sweet, witty blondes, is transformed by Zemeckis into a fiery, vengeful redhead with a piercing gaze, voracious libido, and murderous tendencies. All three actors play against type, and they do it wonderfully. Their performances, which drive the film, are not overshadowed by the technical mastery or the sensational visual effects.

A few words on the effects. The early 1990s marked the dawn of a new era—computer-generated visual effects. Until then, cinematic wonders had relied on optics, mechanics, and photochemical processes. Robert Zemeckis, one of the first directors in cinematic history, was quick to embrace digital manipulation, which became a powerful tool in the creation of his future films. Death Becomes Her is a remarkable showcase of technology that, thanks to epic films like MCU and X-Men, is now standard fare for today’s moviegoers who marvel at special effects. In 1992, however (just one year after Terminator 2 and one year before Jurassic Park), this radical approach to digital animation and the digital retouching of conventional effects (blue screen, models, puppets) was a total novelty, deservedly winning an Oscar for Ken Ralston’s team.

is a mix of the typical image of Hollywood luxury, horror elements, and occasionally even expressionistic lighting and wide-angle shots that distort reality. Even the hospital, the only somewhat “normal” setting, is presented as a nightmarish place.

Robert Zemeckis and his longtime cinematographer, Dean Cundey, skillfully used in-frame editing and filled the scenery with mirrors. Filming among mirrors without capturing the crew’s reflections is notoriously challenging. Mirrors appear in almost every scene of the film.

Each of the three main characters’ faces is shown in reflection several times. In the mirror, Madeline sees both her ugliness and her new self. Helen practices her devious tricks in front of a mirror. The fire from the fireplace is reflected in Ernest’s glasses. In the German Expressionist style, continued by directors like Tim Burton in Batman, the mirror symbolizes purity. Even when the worst villain looks in a mirror, it only reflects an unsullied image of the person, devoid of flaws and wickedness. Zemeckis subverts this mirror metaphor with full irony. Madeline and Helen see their true faces in the mirror, revealing physical flaws (for Madeline) and rehearsing cunning schemes (for Helen).

The original ending, in which Ernest Menville escapes to Europe with a bartender played by Tracey Ullman, was cut. Along with that scene, Zemeckis removed several others, which he felt slowed the film’s pace.

Robert Zemeckis never made another film quite as outrageous and cynical as this grotesque.

In the following years, he returned to epic stories about ordinary people doing great things (Forrest Gump), extraordinary individuals facing jealousy and searching for love (Contact), and deeply moving portrayals of solitude (Cast Away). Zemeckis has always said that his films are about people and aren’t just excuses for technical showmanship. Death Becomes Her fulfills this creative goal, but there’s no denying that this time, instead of interacting with people, we’re dealing with grotesque human marionettes, treated by the creators with merciless, mocking irony.

An excellent film by a remarkable director.