BLOODSPORT. The Greatest Martial Arts Film of All Time?

Best Final Boss

Kids these days don’t know, as one might say, because probably no one born in the 90s or later will understand just how much of a villain Chong Li was for us, the kids of that era, representing South Korea in the tournament. Every time this antagonist appeared on screen, our hearts raced, and when he menacingly flexed his chest, our legs trembled. Chong Li tossed his opponents around like a demon, broke their bones, strangled them to death, and when he felt he was losing, he didn’t hesitate to throw blinding powder in Dux’s eyes. Even when he delivered the iconic line (borrowed from Bruce Lee) that bricks don’t hit back, he inspired fear and respect. For me, Chong Li remains the best, scariest, and most vivid antagonist in the history of martial arts cinema.

In terms of instilling fear and panic among his opponents and viewers, only Tong Po from Kickboxer (which came out a year later) comes close, smashing his bare leg against concrete pillars. The role of Chong Li, who showed no respect for Dux, was played by veteran martial arts actor Bolo Yeung, who by the time of Bloodsport had already appeared in nearly a hundred films. Born in China, Yeung was 42 when he took on the role, and he had previously suffered a beating from none other than Bruce Lee in Enter the Dragon (errata: the beating actually came from John Saxon while Bruce just watched – thanks to the readers for catching that). He portrayed the terrifying, merciless warrior in Bloodsport so convincingly that even today, when I see photos of a smiling Van Damme and Bolo Yeung posing together years later, I still wonder how these two sworn enemies can be in the same shot without tearing each other’s throats out.

Best Soundtrack

Alright, I’ll admit that, objectively speaking, the most famous soundtrack ever from a martial arts movie is probably the one from Mortal Kombat, though it owes much of its success to the epic main theme. Subjectively, however, I value Paul Hertzog’s composition for Bloodsport much more. It’s an excellent soundtrack, just as enjoyable with the movie as it is on its own. Hertzog, a very enigmatic musician, also created the soundtrack for Kickboxer a year later and Breathing Fire in 1991 (another martial arts film, this time starring Bolo Yeung), but he didn’t continue his career as a film composer. Allegedly, he left Hollywood due to creative differences, as the electronic music so characteristic of the 80s started to fall out of favor in the 90s. So what makes the Bloodsport soundtrack, Hertzog’s hallmark, so great and timeless?

The tracks perfectly reflect the drama and energy of each fight, adapting their tempo and intensity to the flow of the action. When Chong Li steps into the ring, the music becomes slower, heavier, and more aggressive, making us feel even more respect for this merciless beast. When lighter and more agile fighters dominate, the music speeds up significantly. And when Frank Dux fights, the score becomes livelier and more upbeat, emphasizing Dux’s physical prowess and speed, complementing his protagonist’s graceful fighting style. Hertzog’s compositions, along with three songs written specifically for the film, are the epitome of 80s music, full of electronic sounds skillfully intertwined with Far Eastern influences.

As Dominik Chomiczewski writes:

Hertzog’s score could be described—perhaps imprecisely—as a mix of synth-pop, rock-pop, and New Age, supported by essential orientalism. The first track, ‘Kumite,’ already gathers these elements, giving us a preview of the rest of the album. Subtle synthesizers accompany parts written for the guzheng, an 18- or 21-string instrument sometimes colloquially called a Chinese harp. These then give way to a ‘Moroder-esque’ rhythm that forms the basis of much of the action scenes’ scoring.

The full soundtrack is available on YouTube, and I highly recommend listening to it. For newcomers, it might be a fascinating musical discovery (as the music still sounds surprisingly modern despite being over 30 years old), and for old-timers like me, it’s a touching musical trip down memory lane.

Excellent Production Quality

In today’s cinema, it’s the norm for the camera to swoop between fighters, performing all sorts of fancy moves and capturing the action from angles we didn’t even know existed in geometry class. But in the 80s, not just martial arts films but all movies were shot in a more straightforward manner and edited just the same. Action cinema was revolutionized by James Cameron at the time, slicing through The Terminator with the precision of a chef cutting meat in a Chinese restaurant. Just take a look at how dynamically the scene at Tech Noir is edited, where Kyle Reese pumps a few rounds into the T-800 from a shotgun. Bloodsport was cut with similar flair (as were the fights in No Retreat, No Surrender two years earlier, showcasing Van Damme’s skills).

The elegant and well-thought-out cinematography, meticulously capturing every punch (combined with the excellent music), completes the spectacular image of a film that could claim the title of the most beautifully shot martial arts movie. Bloodsport also features a lot of slow-motion shots, always used in the right place and at the right time. The scene where the blinded Frank Dux screams his frustration to the world in slow motion because he can’t see Chong Li is a small masterpiece of cinematic expression, though some people mock this intense, screen-shattering moment. But unfairly so.

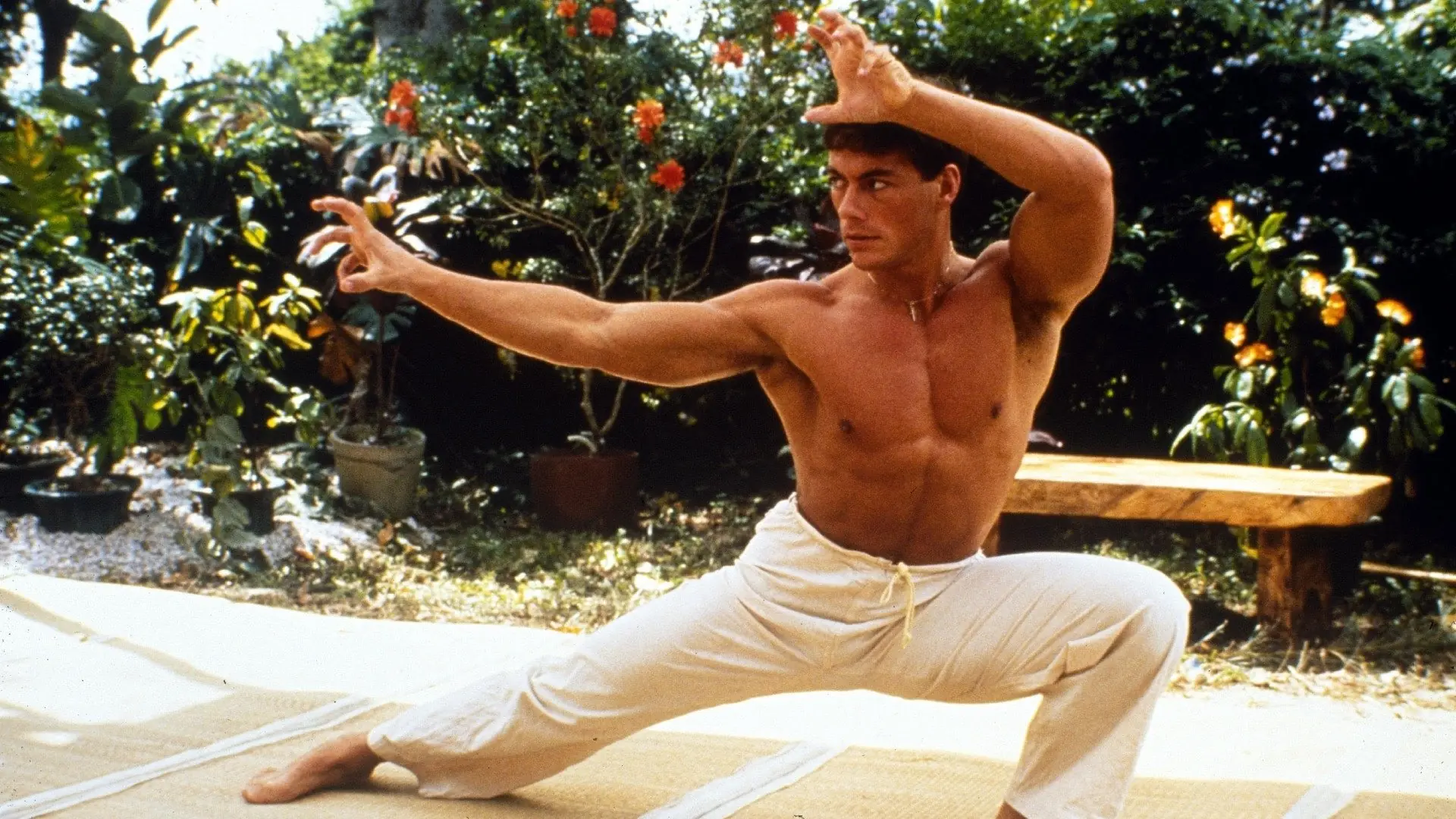

The Best Splits In The Business

Actually, I should say the only splits in the business, because I can’t recall any other actor who could boast such flexibility as Van Damme. Even Chuck Norris, who supposedly did every push-up ever, didn’t try to compete with Jean-Claude when it came to the splits. In Bloodsport, this remarkable ability of Van Damme’s is emphasized heavily (in no less than seven scenes), and its most spectacular version can be seen in the final fight. Of course, I’m talking about the painful slap with his airborne spinning kick—a spectacular 360-degree kick in full mid-air splits. Jean-Claude Van Damme is the only martial artist in the world who can pull this off, or at least the only one who does it on camera.

This airborne, full-spin split kick remains Van Damme’s signature move (brilliantly used in that Volvo ad a few years ago), featured in most of his films (Cyborg, Timecop), but best showcased in Bloodsport. In addition, the Belgian muscleman demonstrates a wide range of other skills during the fight scenes, performing everything with balletic grace and elegance, bringing to life his early dance training. It’s a shame Van Damme received a Golden Raspberry nomination for his debut in the leading role, because although his performance might not have been outstanding, he played the likable soldier-karateka quite well.

Bloodsport Vs. The Competition

We’ll skip over the pitiful inventions like the three lousy Bloodsport sequels (Bloodsport 2, Bloodsport III, Bloodsport: The Dark Kumite) and move on to more sensible titles. The closest competition for Newt Arnold’s cult classic is Kickboxer, released a year later, with a similar plot (minus the big tournament theme) and a similar crew on board. Once again, Jean-Claude Van Damme trains and seeks revenge, and once again, the villain is a serious badass – Tong Po (played by the same actor whose leg Chong Li broke in Bloodsport). There were generally fewer fight scenes in Kickboxer, but the final fight sequence, featuring fists wrapped in shards of glass, sent the emotions of kids at the time into overdrive. The movie also includes the famous scene of Van Damme drunkenly dancing (which some mocked – unfairly, in my opinion) and at one point motivated people to practice splits and martial arts in general. Kickboxer, known back then as Karate Tiger 3 (although no one had ever heard of Karate Tiger 2; Karate Tiger 1 was the VHS-era No Retreat, No Surrender), didn’t stand the test of time as well as the title I hold dear and remains somewhat in the shadow of its older brother.

Some might say that the crown of kickboxing cinema should go to Enter the Dragon, also based on a tournament-style script. But for me, Robert Clouse’s movie doesn’t have enough of Bruce Lee fighting, and there’s too much of a dramatic plot and… John Saxon, shoehorned into the script (because how could there be a Chinese lead in an American movie?), despite having zero martial arts skills. And I was never really a fan of the clawed villain – aside from the hand with blades, which left Bruce with those iconic cuts on his face and chest, he didn’t display any particularly impressive kung-fu on screen. In summary, what I love in Enter the Dragon is the underground fight scene where Bruce Lee takes on guards from all sides, but that’s not enough for me to consider Robert Clouse’s film a competitor to Bloodsport. Other Bruce Lee films might also seem pretty weak in terms of plot and boring between the fight scenes to today’s viewers. At least I fast-forward through the dialogue scenes because I want to watch the “meat,” the phenomenal fight scenes (which, to be clear, I’ll never deny) performed by Bruce Lee. I don’t have that problem with Bloodsport, which is enjoyable both as a whole and in parts.

Jean-Claude Van Damme himself tried to match the cult status of the 1988 film with the 1996 tournament film The Quest, based on another one of Frank Dux’s fabricated stories. All I can say about that movie is that it hasn’t aged a bit, because it was just as terrible on release day as it is today. As we slowly wrap up this uneven Bloodsport vs. The Rest of the World battle, we arrive at the already mentioned Mortal Kombat. Paul W.S. Anderson’s 1995 film is, first of all, too niche, catering to viewers familiar with the game; second, the actors’ preparation for the fight scenes (especially the actress playing Sonya Blade) leaves much to be desired; and third, the special effects in Mortal Kombat have aged as quickly as that German from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade after drinking the wrong Holy Grail water.

We also had The Karate Kid (I can’t stand that movie or the main character), which could clean the blood off the mat for Bloodsport, and Best of the Best was indeed an emotional drama but only a one-time watch, so Newt Arnold’s film didn’t need to worry. Today’s cinema, to put it very briefly, is all about the likes of Champions, Ong-Bak, The Raids, or The Night Comes for Us, among others. And while they are great to watch, and the actors’ skills are undeniably impressive, there’s too much sensationalism and violence for violence’s sake in these titles for them to become universal, timeless cinema that conveys something more than just a display of brute force charging through hordes of opponents armed with sticks and machetes.