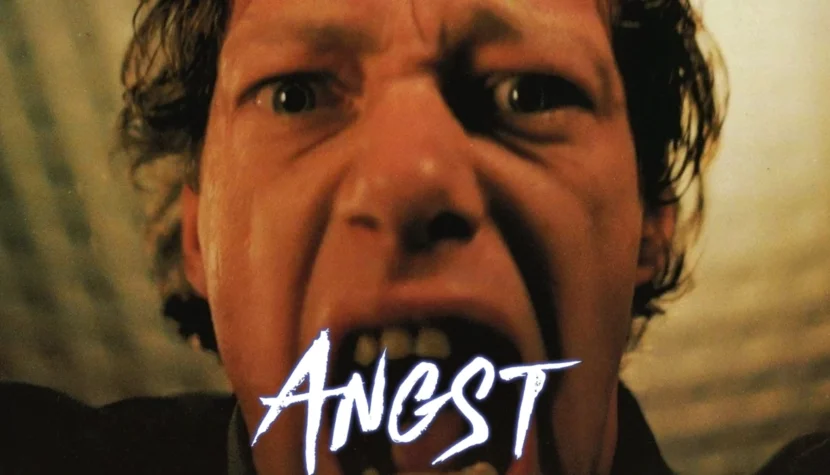

ANGST. A Psychopath Simulator of a Movie Explained

In the early decades of the genre’s existence, there was a prevailing belief that to fit within the confines of horror, a film had to contain supernatural elements – werewolves, vampires, monsters, ghosts, or other types of apparitions.

Later, with the popularization of films about serial killers, this type of restriction was gradually abandoned in favor of a simpler but much broader definition, according to which horror can be recognized by the director’s approach to the concept of fear. The most interesting and probably the most comprehensive classification was proposed by Stephen King in his book dedicated to horror, Danse Macabre. Angst

According to King, horror is a work that can operate on three levels. On the first and simplest level, it evokes disgust through macabre or repulsive characterization. On the second level, it frightens, but this fear fades after the viewing ends. On the third and most advanced level, requiring the greatest creative awareness from the director, it induces anxiety, a subtle, undefined feeling of terror or dread that is difficult to shake off even long after watching the film. If we accept the division developed by the author of The Shining, it can be argued that the highest level is reserved for outstanding, fully thought-out works, far from conventionality, addressing delicate and problematic themes. Reaching the third level means simultaneously breaking with the concept of “safe” fear, according to which we like to watch horror movies because we want to experience a controllable surge of adrenaline associated with a feeling of anxiety. A film at the highest level goes beyond cinema, remaining in the viewer’s mind and not letting itself be forgotten. Such is Angst.

Directed by Austrian filmmaker Gerald Kargl, Angst was a forgotten film for many years, omitted in various rankings and encyclopedias. The likely reason for this was its very limited distribution – the film was entirely financed by the director, who later had trouble finding a distributor (mainly due to the level of brutality), resulting in Angst being distributed almost exclusively on VHS tapes in the 1980s. The director recalled years later that to make his film, he took out loans that he had to repay for a very long time. Only in the twenty-first century, with the advent of the internet, was Angst rediscovered and immediately appreciated, mainly due to its original approach to the subject matter and its suffocating atmosphere.

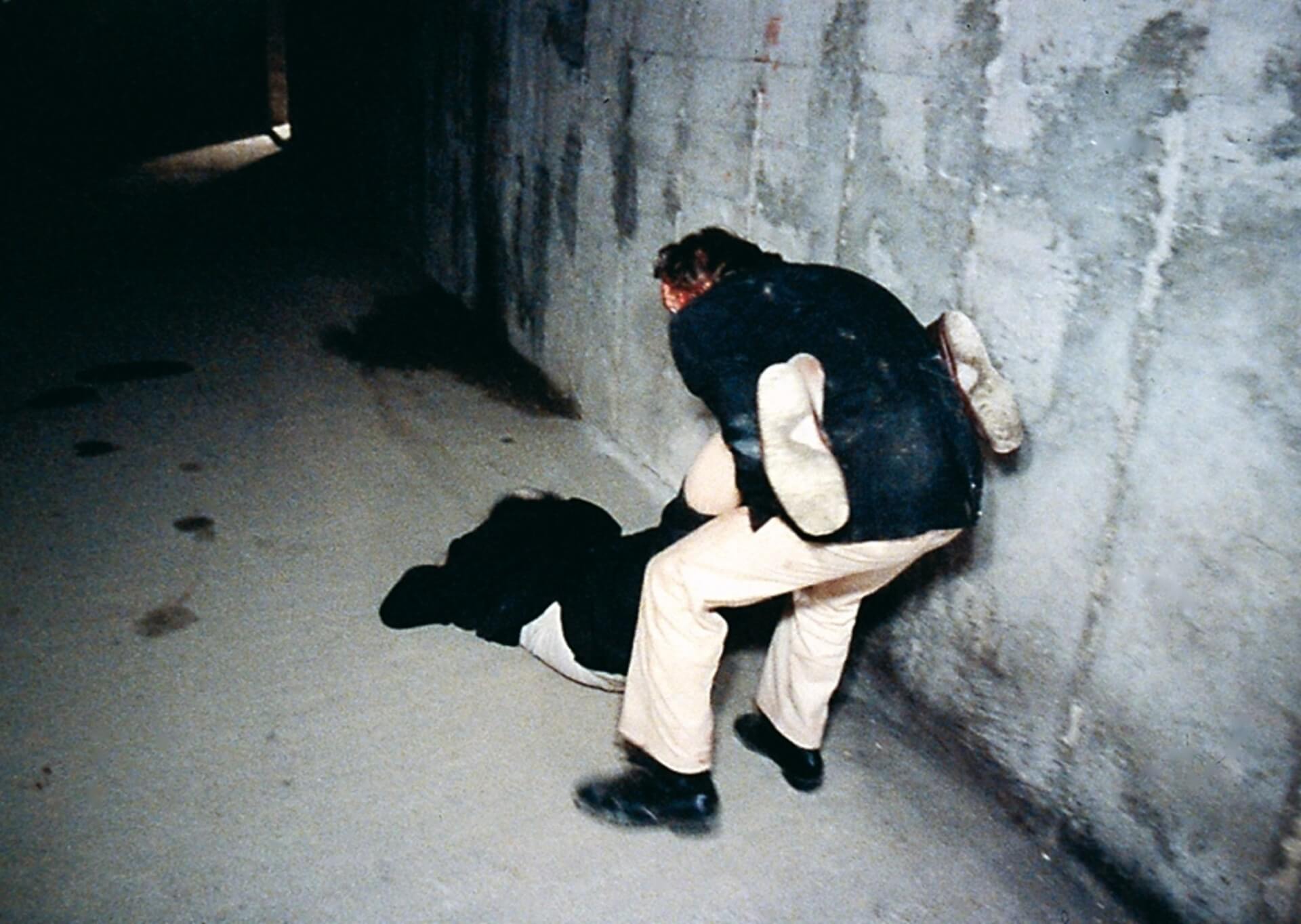

The main character of Angst is an unnamed murderer, imprisoned in an Austrian jail. We meet him at the moment he is released after serving a sentence for stabbing his own mother. From the beginning to the end of the film, the events are accompanied by an off-screen narration by the main character – he comments on his actions, talks about his past, childhood traumas, and his desires. After being released from prison, the murderer, played by Erwin Leder, immediately informs the viewer that he intends to kill again, that it is the only thought that echoes in his mind. This time, however, he plans not to get caught. After a failed attempt to kill a taxi driver, he flees to a randomly found villa, which he assumes is abandoned. To his surprise, he discovers that a three-member family lives there – a sickly, elderly woman, her daughter, and a disabled son permanently confined to a wheelchair. For the main character, this creates the perfect conditions to unleash his impulses – he rampages through the house in a murderous frenzy, killing all three, then packs the bodies into a car and escapes, planning to use his victims’ corpses in his future crimes. However, he gets into a minor car accident and is soon captured by the police in a roadside cafe’s parking lot. The film ends with a scene in which the main character opens the car’s trunk, proudly presenting his “work” to the police and cafe patrons, hoping to instill terror in them. The action takes place within one day.

The main character of Angst stands in contrast to the murderers typically portrayed in cinema. He is not interesting or attractive to the viewer, does not act according to a plan, and is not driven by a specific ideology. At first glance, he is an ordinary, unremarkable man, devoid of any distinctive characteristics. In psychology, such cases are referred to as disorganized serial killers because they are unable to predict their actions, making them very difficult to catch. A disorganized killer attacks by surprise, spontaneously, does not stalk his victims, does not devise a plan of action, almost always uses brute force, and is usually confused and scared during his arrest, rarely attempting to defend himself. Therefore, it is difficult to find logic in the actions of the main character of Angst – he simply gives in to his murderous fantasies, does not fully control his actions, acts under the influence of his desires, and often makes mistakes that an organized killer would not make.

However, depicting the actions of such a psychopath was not Gerald Kargl’s only goal. Angst is primarily a study of disease and addiction. The terrifying actions of Erwin Leder’s character are illustrated by a cold, almost emotionless commentary – the murderer talks about how his mother and stepfather abused him in childhood, his first attempts at crime, and the murderous fantasies that have accompanied him since childhood. Angst is the story of an antisocial, sick man whom no one ever tried to help. It is hard to blame him for his deeds because he commits them almost without awareness, in a murderous frenzy, without the desire for any material gain. The main character repeatedly states that he primarily wants to see fear in his victims’ eyes, that this is the only thing that can calm him and give him momentary happiness. He cannot escape the trap of perpetual feelings of wrong, built by the humiliations he suffered in childhood. Killing is his only way to free himself from the terrifying turmoil in his mind, but it is also a form of blind revenge: for his lost childhood, for the wrongs he suffered, for the lack of understanding. The calm and cold commentary contrasts here with the terrifying events depicted on screen.

Therefore, being in a penitentiary is not really a punishment for the main character – he lives in eternal isolation anyway, locked in his sick mind, with no chance of improvement. In prison, his murderous fantasies serve as a kind of valve (as he himself mentions), allowing him to survive the time without harming people in the real world. At the same time, he constantly lives in fear and an irrational need for revenge, which determines his later actions when he is free. The film’s title, which can be translated as “fear,” “anxiety,” “to cower,” is very telling – it signifies not only the fear felt by the main character’s victims but, above all, the continuous feeling of dread and terror in which the murderer himself lives. It is worth noting that he only attacks weak, defenseless people, and when he encounters a strong opponent, he immediately flees.

In the finale, the emotional and psychopathic actions of the main character are juxtaposed with the dry verdict of the jury, suggesting a sentence of life imprisonment because the murderer “was fully responsible for his actions.” The film’s message seems clear – such individuals should not simply be locked up, as it doesn’t help. They should primarily be treated.

The director does not employ any techniques to make the story more attractive – he does not build suspense, does not try to surprise the viewer, and does not use tricks typically employed in the broader genre of horror cinema. Both Gerald Kargl and cinematographer Zbigniew Rybczyński believe that introducing elements of entertainment into this type of cinema would be a manifestation of cynicism. Thus, watching the described film is by no means a pleasure, nor should it be. Thanks to the skillfully built atmosphere, the crimes committed by the main character become terrifyingly close, almost tangible. The director does not omit any details – all the murders are presented in a precise and fiercely realistic manner. Watching Angst feels like a nightmare that must be endured to the end.

From a formal perspective, every element of the film’s construction is subordinated to emphasizing the main character’s alienation while simultaneously bringing him closer to the viewer. Zbigniew Rybczyński often uses high-angle shots, where the camera follows the murderer from above. He also frequently employs close-ups, mostly showing what occupies the thoughts of Erwin Leder’s character at any given moment (for example, in the bar scene where two girls sitting at the counter are filmed as if from the point of view of the main character’s warped psyche, combining his murderous urges and sexual desire). The most interesting shots, however, are those filmed with a camera mounted on a rig around the killer’s head – the character remains in the center of the frame, while the camera moves freely around him. Combined with the off-screen narration, this creates an extraordinary effect, allowing the viewer to “enter” the mind of the character, making Angst a kind of “murderer simulator.”

The result is both overwhelming and repulsive – one could say that Gerald Kargl reverses the mechanism of identification with the protagonist. The director does not try to present the murderer in a way that would make the viewer want to identify with him; quite the opposite – at every turn, he emphasizes his repulsiveness, while forcing the viewer to inhabit the killer’s mind. The repulsive, disgusting protagonist in Angst serves as a guide through his own psyche – a persistent, unpleasant guide from whom one cannot escape, but with whom one has no desire to identify. These elements cause the viewer to feel disgust (even a simple act like eating sausage is filmed in a way that makes it seem repulsive) and a certain compulsion to see the world through the lens of a sick mind. This is best shown in the roadside bar scene, where the subjectivity of the narration reaches its peak—the main character “sizes up” the patrons in search of a potential victim, and the viewer is forced to do so along with him.

It is worth noting that Kargl never gives the viewer even a shred of hope – in one of the final shots, the camera performs a 360-degree rotation, symbolizing the vicious circle of crime and punishment in which the main character will remain for the rest of his life. This harrowing image is complemented by Klaus Schulze’s cold, electronic music, illustrating the film’s key scenes, as well as specific, unsettling background sounds (like dripping water at the beginning and during the end credits), which serve to intensify both the film’s atmosphere and its message.

Angst remains, even today, despite being more accessible, a little-known film, recognized mainly by horror fans and enthusiasts of the psychopathic murderer theme. Meanwhile, it is one of the most uncompromising, original, and striking works I have ever seen and one of the most evocative nihilistic horror films in the genre’s history. It is hard to find another film that approaches the subject matter in such a comprehensive manner (perhaps aside from Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, released a few years later) and does so without any concern for the viewer’s comfort – Kargl wants to terrify us, to instill unease, and he is not afraid to use every possible means to do so. Considering that film murderers are very often portrayed as fascinating and devilishly intelligent, it is worth looking at the almost exact reverse of that archetype – a seemingly ordinary man whose psychopathy we get to know “from the inside,” rather than through eccentric characterization. It is not a pleasant experience, but it brutally brings one down to earth.