CONSPIRACY THRILLER. Political movies, from which you will get PARANOIA

The world of politics symbolizes power, influence, privilege, but also the hostility of the gray citizen, to whom politics, and especially its highest levels, are associated with corruption, swindle and vacuousness. Representatives of the government have an impact on what life is like for the common man, so it is not difficult to believe that there is more behind their activities than what we hear in the media. In the history of the world, many improbable situations have happened, where not all the pieces fit together, so conspiracy hypotheses are formed to explain certain things. But conspiracy theories are also stories that go against what is considered to be the common truth. These are not always things related to politics, for example, there is a theory that William Shakespeare was just a figurehead, and the works he signed actually have multiple authors.

7. Death of a Corrupt Man (1977), dir. by Georges Lautner

French conspiracy thrillers are material for a separate chapter. In addition to the works of Costa-Gavras, who works in France (Z, State of Siege), the leading entries of the genre include: Nada (1974) by Claude Chabrol, The French Detective (1975) by Pierre Granier-Deferre, Judge Fayard Called the Sheriff (1977) by Yves Boisset, I… For Icarus (1979) by Henri Verneuil, Three Men to Kill (1980) by Jacques Deray, and to some extent The Professional (1981) by Georges Lautner.

The title death of a corrupt man is the beginning of a series of mysterious events, the centerpiece of which is a diary with a record of shady deals. Politicians, businessmen, industrialists, financiers can lose their reputations after the contents of the notebook are revealed. The main character is Xavier Maréchal (Alain Delon), who is an incorruptible and violence-avoiding man. When his buddy is murdered, Maréchal undertakes his own investigation to find the killer. A specialist in entertainment cinema (and the director of the psychological drama The Road to Salina), Lautner’s film is a work that skillfully combines an ambitious look at corruption and depravity with passionate thriller cinema with an obligatory car-stunt scene supervised by Rémy Julienne. The film is based on a novel by Jean Laborde (also known as Raf Vallet), author of Adieu poulet! (aka The French Detective), which was made into an excellent film starring Lino Ventura and Patrick Dewaere.

When a number of conspiracy thrillers were made in France, the office of president was occupied by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (who died on December 2, 2020 from complications after COVID-19). During his term (1974-1981), the last death sentences were carried out in the country. One of the well-known actors supporting the president was Alain Delon, who was the producer of Death of a Corrupt Man, a film showing Paris as a hotbed of corruption and lawlessness, as the stables of Augeas in need of cleansing, though it seems impossible. After the 1973 oil crisis, unemployment rose, conflicts escalated, violence intensified. Solid reforms and decisive action are needed. The cinematography by Henri Decaë (Elevator to the Gallows, Purple Noon, Le Samouraï) is kept in austere tones, the aura of pervasive cynicism is overwhelming. Philippe Sarde’s music, which includes a saxophone solo performed by American jazzman Stan Getz, also maintains the right atmosphere for the story. Even Michel Audiard, a master of witty dialogue, had to restrain his humor and go for seriousness. Although the film was a box office success, thanks in part to a great cast (in addition to Delon: Ornella Muti, Stéphane Audran, Mireille Darc, Maurice Ronet, Michel Aumont and – last but not least – Klaus Kinski), the filmmakers may have felt disappointed, as a much higher financial result was achieved by Belmondo with his comedy Animal.

8. I... For Icarus (1979), dir. by Henri Verneuil

From today’s perspective, films from the 1970s whose intrigue refers to the Kennedy assassination may seem late and outdated. But to tell a story about a political conspiracy wisely, avoiding cliché, it’s worth waiting at least a decade after the unexplained events. The first major feature film on a political assassination in Dallas was made in 1973 (Executive Action, directed by David Miller), and the most artistically mature wasn’t made until 1991 (JFK, dir. by Oliver Stone). Interestingly, there was even a spaghetti western inspired by this assassination – The Price of Power (1969, dir. by Tonino Valerii). Its plot is set at the time of the assassination of President James Garfield (1881), but the location of the event and the circumstances surrounding it have been altered in such a way that they are clearly associated with JFK. The French also picked up the theme, but didn’t do so explicitly, taking full advantage of the possibilities of literary fiction and setting the action in a fictional country. This country doesn’t exist, but the problems that haunt it are as authentic as possible. The president is assassinated, and the results of the official investigation are hastily announced, just to close the case. Prosecutor Henri Volney (Yves Montand) springs into action, intent on uncovering the truth.

For Henri Verneuil, director of excellent crime movies (Any Number Can Win, The Sicilian Clan, The Burglars, The Night Caller), a project called I… For Icarus was by design a more ambitious production. Based on meticulously built tension and an atmosphere of constant danger, the film is aimed at an intelligent viewer looking for not only action, but also reflection in cinema. Reflection on the questionable power structure, the ineptitude of the security system, the dark human nature and the psychological aspects of crime. The director proved to be a keen observer of everyday life, and his film contains a brilliant commentary on the importance of truth and justice in the modern world. A great punchline is the finale that explains the meaning of the title. And, as always, a good commentary is provided by Ennio Morricone with his music (this is Verneuil’s sixth and last film with a Morricone soundtrack).

The key to interpreting the film may be the psychological experiment conducted by Stanley Milgram in the early 1960s, which occupies an important place in the script. The study was to see how a person acts when he has a “manager” over him, someone who controls him and encourages him to use violence. When a man is given a task by someone, then it’s easier for him to do it, because he feels impunity, he can always then blame it on his superior. This is how people acted in war, but also in peacetime this method proves to be effective, and it’s very possible that it also worked in the case of Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby, and maybe even members of the Warren Commission.

9. Murder by Decree (1979), dir. by Bob Clark

A lot of conspiracy theories arose around the murders of Jack the Ripper. One of them was debunked rather quickly, but nevertheless inspired filmmakers. In the early 1970s, a certain Joseph Gorman (also known as Joseph Sickert) claimed to be the illegitimate son of Alice Margaret Crook and famed painter William Sickert (who was portrayed as Jack the Ripper in Patricia Cornwell’s book Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed, published in 2002). Gorman said he had heard stories from his father about the British royal family’s connection to the Whitechapel murders in 1888. Reportedly, his grandmother, Annie Crook, secretly married Albert Victor, grandson of Queen Victoria, and then gave birth to a child, Alice (Gorman’s mother), who was the rightful heir to the English throne. To hide this fact, the royal family, with the help of the court physician Sir William Gull, got rid of witnesses, while Annie Crook, the prince’s secret wife, was placed in an insane asylum.

This version of the Ripper murders was popularized by writers Elwyn Jones and John Lloyd, who co-wrote the 6-part series Jack the Ripper (1973) about the investigation led by fictional detectives Charles Barlow and John Watt. They later wrote a book about it, The Ripper File (1975). British journalist Stephen Knight, in turn, based on this theory and adding his own investigative results to it, wrote Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution (1976). Historians and criminologists vehemently rejected this version of events, and even Gorman himself admitted that he had made it all up. But the theory survived in pop culture, and based on it American director and producer Bob Clark, along with British screenwriter John Hopkins, created the dark retro thriller Murder by Decree. As in A Study in Terror (1965, dir. by James Hill), they linked Sherlock Holmes to the Jack the Ripper case, but used as a solution a recent conspiracy theory linked not only to the English royal family, but also to Freemasonry. Detective Sherlock Holmes (Christopher Plummer) and Dr. Watson (James Mason), characters invented by Arthur C. Doyle, tread on slippery ground, as authentic characters stand in their way: the commissioner of the London police, Sir Charles Warren (Anthony Quayle), the British prime minister, the Marquis of Salisbury (John Gielgud) and the aforementioned Annie Elizabeth Crook (Geneviève Bujold).

Bob Clark’s British-Canadian production is distinguished from other screen adaptations of Holmes’ adventures by its greater emotionality. In Plummer’s interpretation, the detective is characterized by empathy, does not treat the case as routine, but gets heavily involved and feels remorse for not protecting one of the victims, Mary Kelly (Susan Clark). His final tirade in front of the three members of the Masonic lodge is an excellent culmination of the story, accusing the politicians of a conspiracy of silence, but also accusing himself of not acting effectively enough. Watson, in turn, isn’t the same as in others interpretations. James Mason reportedly agreed to play the role only on the condition that Dr. Watson be treated with more respect than usual.

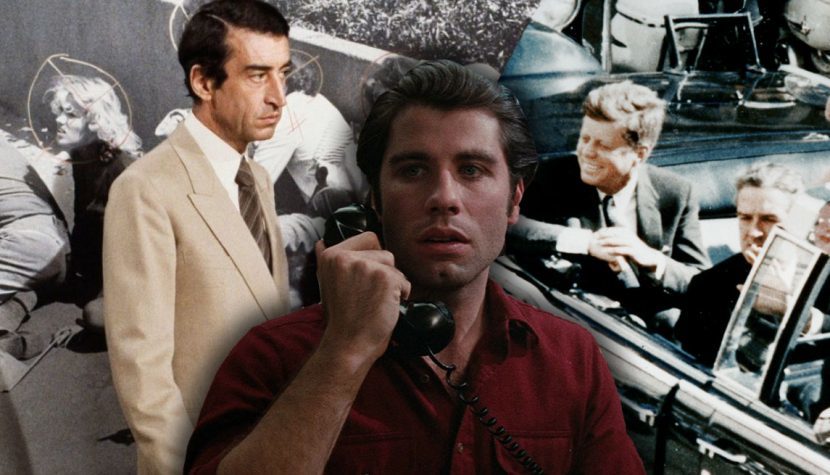

10. Blow Out (1981), dir. by Brian De Palma

Original title of the film brings to mind Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966). This is certainly not an accidental resemblance. The protagonist of that film is a photographer who, in the course of doing his job, captured something he shouldn’t have. He became an unwitting witness to a crime. Brian De Palma in his film presented a similar hero, also somewhat inspired by the authentic figure of Abraham Zapruder, who filmed the assassination of President Kennedy.

The director, who is a fan of Alfred Hitchcock, began his film with a scene that can be described as a parody of the shower scene from Psycho (1960). Tension is brilliantly built up to a certain point, only to be spoiled when the heroine screams. This blooper is, of course, intentional, as an important motif turns out to be the search for the perfect scream. It is for this purpose that sound engineer Jack Terry (John Travolta) goes into the open air to record something. And he witnesses a car accident, the victim of which is the governor and also a presidential candidate. The hero manages to save a girl named Sally (Nancy Allen), whom the politician was presumably driving home after spending the night with her. Sensitive to sounds, Jack heard the gun shot before the accident and the sound recording he made confirms it. The problem is that a certain group of people are keen to have the politician’s death considered an accident rather than an assassination attempt. Jack and Sally are targeted by a mysterious murderer (John Lithgow), who, to confuse the police, kills several random people.

In addition to his directorial craftsmanship, De Palma also showed literary talent, creating an original and precise intrigue, ambiguous enough to provoke thought. The film is largely a story about people tormented by guilt, trying to change their attitude so as not to repeat the mistakes of the past. Jack is remorseful about a former police action when the microphone he installed malfunctioned, contributing to a tragedy. Years later, he got bogged down in low-budget horror films, but unlike the makers of tape-produced slashers, he has no intention of working sloppy, he takes his work very seriously. Sally, too, is trying to undergo a transformation – she was previously an accomplice of a blackmailer, but the accident in which she almost died is for her, as it were, the beginning of a new life and a chance to improve. With this film, the director pays homage not only to his favorite classics (mostly with voyeuristic themes – Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Antonioni’s Blowup, Coppola’s The Conversation), but also to the underappreciated workers of the film industry, the sound engineers. It’s hard not to appreciate the stylish visuals, for which outstanding cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (Oscar for Close Encounters of the Third Kind) was responsible. Long after the screening, the beautiful music of Pino Donaggio stays in the mind – presented in the finale, it can cause an explosion of emotions.