ANDRZEJ WAJDA. The Complete Works of a Polish Master

He is a true veteran of contemporary cinema, acclaimed both in Poland and internationally. This recognition goes beyond the honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement, which was a mere formality. He is a director whose films are listed among the best in the history of cinema. Importantly, this acclaim comes not from popularity rankings, which follow different rules, but from voices such as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, who count Ashes and Diamonds among their favorite films (both of whom are also veterans, though they debuted several to many years later than Wajda).

Korczak (1990)

Starring: Wojciech Pszoniak, Ewa Dałkowska, Teresa Budzisz-Krzyżanowska, Marzena Trybała

Major Awards: Golden Ducks (nominations: Best Director of Award-Winning Films at Major International Festivals, Best Leading Actor, Best Historical-Costume Film of the Century of Polish Cinema)

Another film where Wajda collaborates with Wojciech Pszoniak. This time, the director tackles the nightmare of the Holocaust in Warsaw. Unfortunately, this production is not entirely successful. In retrospect, films like Schindler’s List, The Pianist, or In Darkness (Agnieszka Holland also wrote the screenplay for Korczak) are more mature artistic reflections on the Holocaust. They more fully capture this traumatic aspect of World War II. While Spielberg or Polanski’s films present a variety of perspectives, Wajda’s film delineates a clear black-and-white division between good and evil, with no shades of gray. Sometimes, Korczak’s care and concern for his wards are touching. However, the entire film does not sustain this continuous, unchanging tone. I am far from saying it is a bad film, but I expected more from Andrzej Wajda. A positive aspect is Wojciech Pszoniak’s performance. Dr. Korczak convinces with his commitment, determination, and uncompromising judgments, but I believe more could have been drawn from this character, and a better film could have been made about him. [Maciej Niedźwiedzki]

The Ring with a Crowned Eagle (1992)

Starring: Rafał Królikowski, Cezary Pazura, Adrianna Biedrzyńska, Piotr Bajor

Major Awards: None

The Ring with a Crowned Eagle was a nostalgic look back for Wajda, an attempt to close the chapter titled Polish Film School. World War II, young people wandering through the ruins of the Warsaw Uprising, and the rise of the communist regime – iconic themes in Polish cinema. Despite clear references to his earlier films (including the famous scene with burning glasses from Ashes and Diamonds) and the effort Wajda put into adapting Aleksander Ścibor-Rylski’s book, The Ring is not a successful film. At times, the master’s touch is felt, with visual suggestiveness (especially in the Uprising scenes) and apt metaphors, but overall, the film is “lukewarm,” and – as we know – one should be either cold or hot. The Ring with a Crowned Eagle works as a sentimental journey, but as a standalone spectacle, it falters, suffering from mediocrity. [Filip Jalowski]

Nastasja (1994)

Starring: Tamasaburo Bando, Toshiyuki Nagashima, Baucho Tsuji

Major Awards: None available

Primarily an extremely hard-to-find film – it is a Japanese production, an adaptation of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, with Japanese actors in the main roles. No rating, as none of the editorial staff has seen Nastasja.

Holy Week (1995)

Main Cast: Beata Fudalej, Wojciech Malajkat, Bożena Dykiel, Wojciech Pszoniak

Major Awards: Silver Bear (Andrzej Wajda, Outstanding Artistic Contribution)

Holy Week marks another return by Wajda to the literary works of Andrzejewski. The director had considered adapting the story as early as the 1960s, but its Jewish themes made the project unfeasible at the time. The adaptation rights changed hands multiple times before finally returning to Poland in the 1990s, allowing Wajda to pursue this long-delayed project. However, the final result leaves much to be desired. Wajda’s vision is starkly black-and-white, lacking the psychological complexity that the characters deserve. This approach is particularly jarring given the film’s themes, which should be rich with morally ambiguous issues. Ultimately, it stands as the weakest adaptation of Andrzejewski’s work by Wajda. [Filip Jalowski]

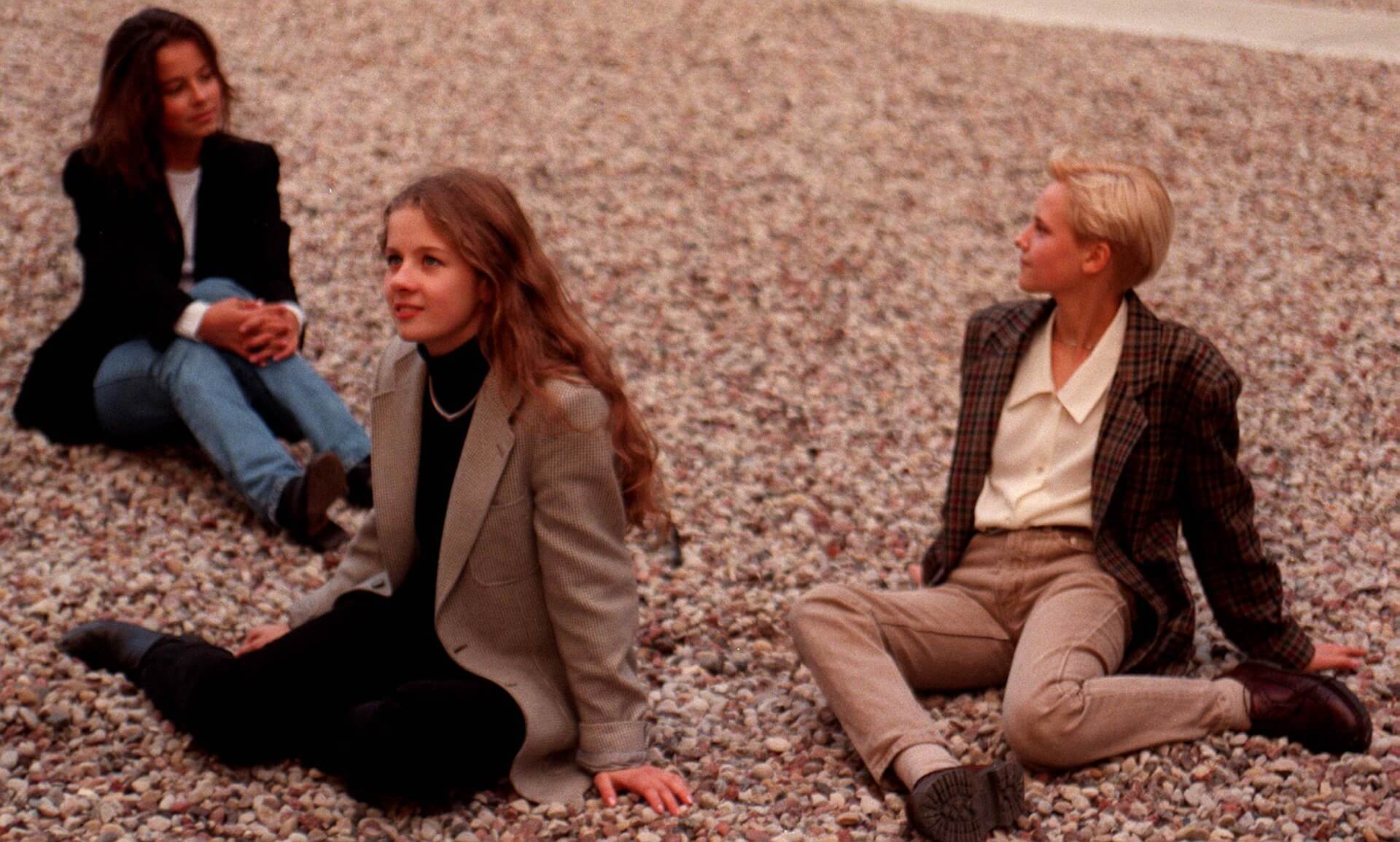

Miss Nobody (1996)

Main Cast: Anna Wielgucka, Anna Mucha, Anna Powierza, Stanisława Celińska, Jan Janga-Tomaszewski

Major Awards: Berlinale (Special Jury Mention for “Promising Role of a Young Actress” for Anna Wielgucka)

This is arguably the worst film in Andrzej Wajda’s entire filmography. The creator of Kanal aimed to appeal to a younger audience by adapting Tomasz Tryzna’s controversial yet critically acclaimed novel Miss Nobody, but the result is a neutered version of the original. It’s unclear what Wajda intended to achieve with this odd blend of coming-of-age story and psychological drama. I remember being terrified by this film as a child, especially the scene where the camera tracks a dirty and battered Marysia as it moves through a bus. However, watching it now, Miss Nobody strikes me as one of the most irritating Polish films of the 1990s. This film is grating and exhausting. The question remains, who is more to blame for this failure: Wajda, who struggled to adapt to a project so different from his previous work, or the weak script by Radosław Piwowarski? The film seems more suited to Piwowarski’s style, which includes similar atmospheric and unsettling elements. The rivalry and intrigue among the friends, with an innocent girl falling victim, is a strong premise. This theme remains relevant today, especially as a critique of a society increasingly made up of opportunists who always choose safe and convenient solutions, even at the expense of their ideals. Marysia (Anna Wielgucka) becomes a “nobody” by abandoning her family and religion, which were once her highest values. Despite being healthy, unlike her younger brother, she was essentially blind—unable to see that she was merely a pawn in a game, and that life is more complex than she imagined. The film’s redeeming qualities include the performances, which make it a pity that Anna Mucha and Anna Powierza wasted their talents on soap operas. Also noteworthy are Stanisława Celińska, Jan Janga-Tomaszewski, and Tadeusz Huk, who brings out the best even in a small role. [Krzysztof Połaski]

Pan Tadeusz (1999)

Main Cast: Michał Żebrowski, Bogusław Linda, Daniel Olbrychski, Alicja Bachleda-Curuś, Grażyna Szapołowska, Krzysztof Kolberger, Marek Kondrat, Andrzej Seweryn, Marian Kociniak

Major Awards: Eagle (Polish Film Award) – Awards for Best Cinematography, Set Design, Sound, Music, Editing, and for Grażyna Szapołowska’s Best Actress

It’s hard not to like this film and appreciate the meticulous care with which it was crafted. If we can momentarily set aside the mental burden of watching the adaptation of Poland’s most obligatory reading, the viewing experience can be immensely enjoyable. Firstly, the film is excellently acted in thirteen-syllable verse by a star-studded cast of Poland’s finest actors, who give their all knowing they are part of something exceptional. Secondly, it is beautifully made, with idyllic landscapes, a wonderfully nostalgic atmosphere, and an excellent accompanying score. In this regard, Pan Tadeusz is sheer delight. Admittedly, it is a summary in its purest form and was also created for commercial reasons, which continues to pay off to this day. Nevertheless, it is an original and remarkable piece of cinema. By the way, it was a huge box office hit, drawing 6 million viewers in Poland—just slightly less than Titanic and Avatar combined. [Rafał Oświeciński]

The Condemnation of Franciszek Kłos (2000)

Main Cast: Mirosław Baka, Maja Komorowska, Grażyna Błęcka-Kolska, Artur Żmijewski, Krzysztof Globisz, Paweł Królikowski, Andrzej Chyra

Major Awards: None

The beginning of 2000 was marked by an Oscar for Andrzej Wajda for his lifetime achievements in film, but soon after returning to Poland, the director began working on his next project. This was his only full-length television film, based on Stanisław Rembek’s 1947 novel The Condemnation of Franciszek Kłos. Often mistaken for a TV theater production, this film blurs the line between television movies and certain TV theater stagings. The plot focuses on Franciszek Kłos (an excellent Mirosław Baka), a Blue Police officer who serves the Third Reich faithfully. Kłos unhesitatingly kills conspirators, Jews, and even children. He is hated by Poles and still treated as a second-class citizen by the Germans—a loyal “dog.” In his mind, he is doing nothing wrong, just following orders, and after all, the Jews did betray Jesus, so how can the Catholic Church defend them? As he receives a death sentence from the underground court, Kłos becomes increasingly fearful for his life; the more he fears, the more he drinks, and in his drunken stupor, he becomes capable of anything—shooting at anything that moves and hacking doors with an axe. Mirosław Baka’s performance is the highlight of this film, reminiscent of his role in Kieslowski’s A Short Film About Killing, where he also played an anti-hero awaiting execution. However, this time Krzysztof Globisz won’t be his lawyer. The film contains very strong moments, such as when Kłos tells his family he wants to commit suicide but insists that his wife and children must die too, as they can’t live in such a cruel world, burdened by the father’s sins. Unfortunately, the biggest drawback of The Condemnation of Franciszek Kłos is its execution—it’s simply hard to watch. Handheld camera work fails miserably in the film’s most pathetic scene, a shootout between Poles and Germans. Kłos and an SS man (an over-the-top Artur Żmijewski), single-handedly driving away an AK unit, look not only bad and unrealistic but downright laughable. There are several more such absurdities in the script. Nevertheless, if we overlook the execution necessitated by the symbolic budget and script flaws, we get a suspenseful, interesting, and valuable film where Wajda examines different facets of patriotism, loyalty to one’s country, religion, and betrayal. [Krzysztof Połaski]

The Revenge (2002)

Main Cast: Andrzej Seweryn, Janusz Gajos, Roman Polański, Agata Buzek, Daniel Olbrychski, Rafał Królikowski

Major Awards: Numerous Eagle Award nominations, but no wins

This is a rather peculiar film in Andrzej Wajda’s body of work. As usual, the creator of Ashes and Diamonds reached for an important text of Polish literature, this time by Aleksander Fredro. In this respect, The Revenge fits perfectly into Wajda’s filmography. What distinguishes the 2002 film is its exceptionally theatrical style. The adaptation of Fredro’s play is strikingly close to the form of a television theater production, with rare stylized sets and costumes and theatrical acting, setting it apart from the rest of Wajda’s works. It’s certainly an aesthetic shock for viewers accustomed to the full-blooded, epic spectacles like The Promised Land, Danton, Man of Marble, or Man of Iron. Nonetheless, one can’t overlook the great enjoyment and engagement the actors brought to their roles. This intimate production allows for a focus on the nuances and details of character portrayals. Roman Polański returns to the screen in The Revenge, reminding everyone of his talent as an actor. [Maciej Niedźwiedzki]

Katyn (2007)

Starring: Jan Englert, Danuta Stenka, Artur Żmijewski, Maja Ostaszewska, Magdalena Cielecka, Andrzej Chyra, Paweł Małaszyński

Major Awards: Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film; Polish Film Award (Orzeł) – Winner for Best Film of 2007, Best Cinematography, Best Production Design, Best Costumes, Best Music, Best Sound, and Danuta Stenka for Best Supporting Actress

Katyń is not Saving Private Ryan. Nor is it Schindler’s List. The criticism that Wajda’s film faced often focused on its lack of universalism characteristic of popular cinema, the superficial nature of its characters, and the patriotic overtones that pervade the frames. However, Wajda aimed for something entirely different – he wanted to evoke the emotions, feelings, values, and needs of those who fought and died at that time. With God on their lips, with a memory of their Homeland, with clearly defined Honor. Typical romantic heroes resigned to their fate but simultaneously seeing the purpose of their death. If we adopt this perspective, Katyń can take on new hues. Also invaluable is the drastic change in the narrative’s tone in the final minutes – nostalgia turns into brutal realism. These are undoubtedly some of the most harrowing depictions of war in cinema history. [Rafał Oświeciński]

Sweet Rush (2009)

Starring: Krystyna Janda, Paweł Szajda, Jan Englert

Major Awards: Polish Film Awards (nominations: Best Leading Actress – Krystyna Janda, Best Music – Paweł Mykietyn), Berlinale (Alfred Bauer Prize, nomination: participation in the main competition), European Film Award (European Film Critics Award – Prix FIPRESCI)

Andrzej Wajda as a postmodernist. The director of The Promised Land accustomed his viewers to opulence (which he broke with in The Revenge) and classical narration. Sweet Rush is, in many respects, a unique film. For the first time, Wajda stops believing in the text he is adapting. This time, life surpasses art. It cannot convey certain states, emotions, and fears. From time to time, the camera leaves the action, slips out of the plot, and the actors stop acting. Therefore, we listen to Krystyna Janda’s monologue about her deceased husband or see the film crew with Wajda himself. This time, Iwaszkiewicz’s story is not enough. Wajda wants to say more, to explore the boundaries of cinema. Sweet Rush is more of a narrative experiment. Not everything in it succeeded. The viewer is often distracted by various digressions, breaking the bond of identification with the protagonist. Often, it feels like watching several edited films rather than one coherent and thought-out statement. [Maciej Niedźwiedzki]

Walesa: Man of Hope (2013)

Starring: Robert Więckiewicz, Agnieszka Grochowska, Dorota Wellman, Maria Rosaria Omaggio, Cezary Kosiński, Zbigniew Zamachowski

What does Walesa: Man of Hope retain from the demystifying ideas of Man of Marble and Man of Iron? In formal terms, it has its rebel – Wałęsa. But dramatically, the focus is more on episodes from Lech’s life than on slapping the old system. Of course, it’s hard to unmask what was officially unmasked 24 years ago, but purely in narrative terms, Wajda skims the surface, with no time for a cat-and-mouse game that, on an emotional level, I might have desired. Nevertheless, one can grumble, wish for less skimming of opposition topics, scoff at historical shallowness and episodic storytelling that builds Wałęsa’s greatness on the principle of “just because.” But the fact remains – it is a very enjoyable viewing with a truly PHENOMENAL Robert Więckiewicz. Every line he delivers, every expression, every gesture is priceless and must be appreciated. [Rafał Oświeciński]