SPIRITED AWAY. Stunning anime masterpiece

Let’s start with Karol Irzykowski. Yes, Irzykowski, even though we are about to embark on a journey to Japan in the early 21st century. One of the most important Polish pioneers in the field of film studies already in the 1920s saw the potential for the slowly developing medium to become art. According to Irzykowski, the greatest artistic value, however, was attributed to one specific type of film – animations. Animated films were supposed to be a way for artists to create freely, unrestricted by the constraints of reality, and although he considered abstract works the pinnacle of cinema as an art form, it is worth risking the statement that Spirited Away, in some respects, could have piqued his interest. Perhaps even admiration – because if Hayao Miyazaki’s masterpiece is not a perfect example of the total creative power of the medium of film, then perhaps nothing is.

How it all came to be

Let’s now move to Japan at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, specifically to a mountain cabin where the nearly sixty-year-old Hayao Miyazaki spends time with his family and a few ten-year-old daughters of his friends. The girls are around ten years old and will soon enter the most turbulent period of their lives, and the already esteemed Japanese director realizes that he has not created anything that would interest them. He believes that his previous works, including My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), and Princess Mononoke (1997), are not what ten-year-old girls would enjoy. So, Miyazaki decides to create something that will captivate them and, as inspiration, turns to the manga that his wards are reading. He is not thrilled with what he sees – the childish stories focusing on first loves and secret crushes on boys are not what Hayao would like to serve to growing girls. He would prefer to create a credible female protagonist who could become a role model for them – so he begins to dig into the almost infinite depths of his imagination, drawing inspiration from memories, folklore, and literature. This is how Chihiro is born.

Miyazaki began working on Spirited Away, utilizing financial support from the American studio Walt Disney Pictures, the rapidly evolving 3D animation technology, dedicated Ghibli staff, and his own creativity. His goal wasn’t just to make another movie but to create a work that would appeal to young audiences, inspire them, and meet their cinematic (and more) needs. Several improvements were needed for the main character’s design to make her likable yet believable, as well as shortening the initially over three-hour-long running time. Spirited Away premiered in Japan on July 20, 2001, and in the United States nearly a year and a half later. In Miyazaki’s home country, it immediately became a massive financial and artistic success, while in foreign markets, the film’s popularity exploded, especially after the 75th Academy Awards ceremony, during which it won the Best Animated Feature Oscar. Today, more then 20 years after its official premiere, Spirited Away is widely regarded as Miyazaki’s greatest achievement in his entire career and one of the best animated films in the history of world cinema.

Related:

Chihiro and Alice

Who is the titular Chihiro/Sen? She is a ten-year-old girl who, along with her parents, moves to a new town. This is not an exciting prospect for her – all she has left from her old acquaintances is a bouquet of flowers and a farewell note, and the prospect of moving raises many doubts. During the journey to their new home, Chihiro’s father accidentally turns onto a forest road, leading the family to a mysterious gate. After passing through it, they find themselves in an abandoned town. The enticing smells of delicious dishes left unattended in one of the local eateries lure Chihiro’s parents, who begin to greedily consume everything in sight and, to Chihiro’s horror, transform into two enormous pigs. The area fills with various kami, Japanese spirits, and Chihiro eventually ends up in a huge bathhouse for spirits, becoming entangled in a series of events where the stakes are the salvation of her parents and herself.

Many texts about Spirited Away make an understandably obvious comparison to Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, so let’s start there because it’s hard not to see the similarities. Both Chihiro and Alice are young girls who find themselves in an incredible world where the laws of logic and physics operate on completely different principles. The journey ends in a profound inner transformation for both heroines. However, there are several differences in Chihiro’s path compared to Alice’s. At the beginning of Spirited Away, Chihiro feels lost, depressed, and uncertain in her new environment, far from her previous, familiar life. She clings to her mother every step of the way, nearly hanging on her shoulder as they pass through the mysterious gate. The same applies to her relationship with Haku, a boy she meets on the other side of the magical bridge leading to the divine bathhouse. Haku saves the girl, but she soon has to reach her destination by herself, and as she approaches a rather dangerous staircase, she almost crawls down the steps, genuinely terrified.

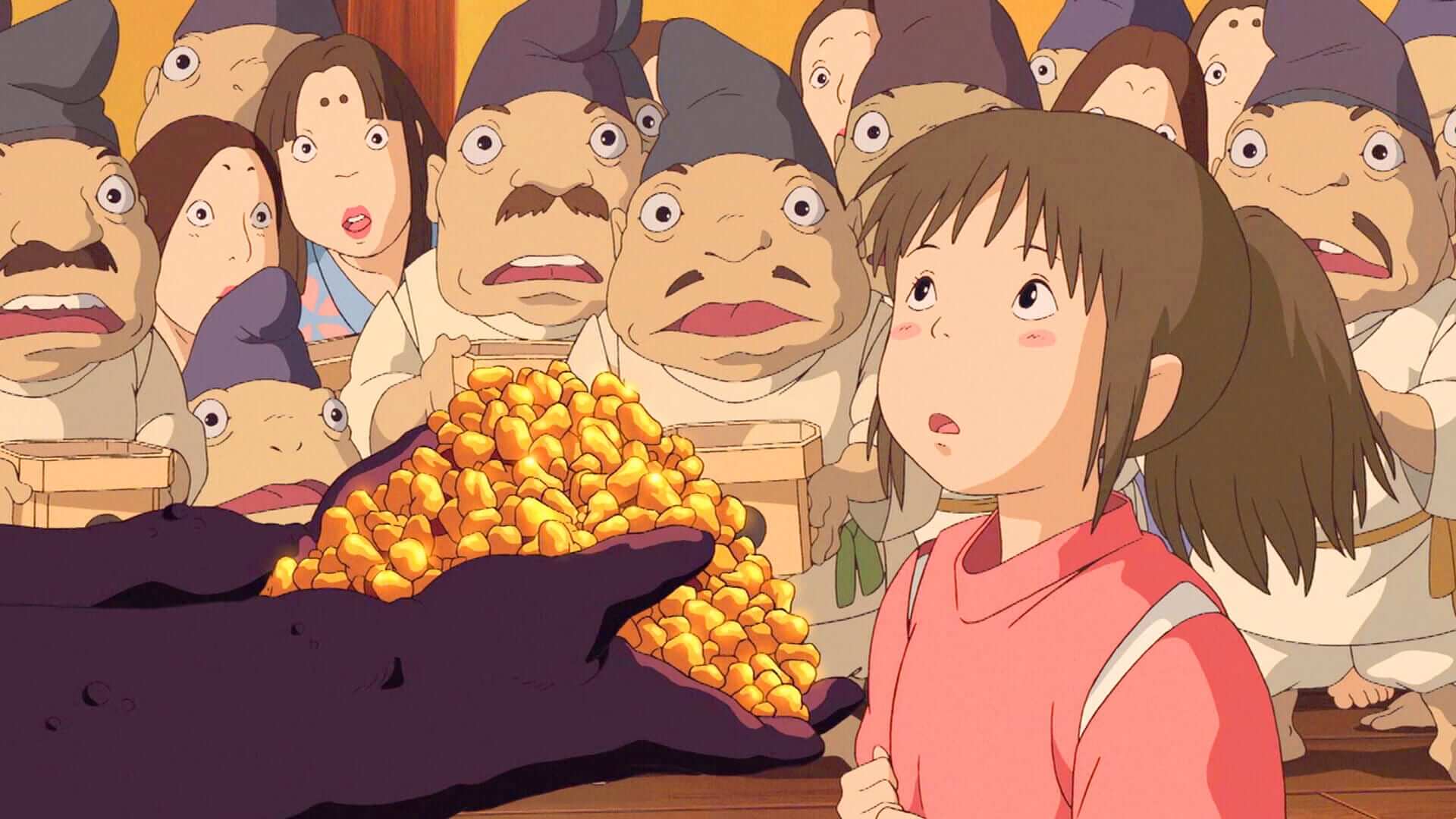

However, as time goes on, the shaken Chihiro begins to change, out of necessity, she starts taking life into her own hands, independently. After getting a job at the bathhouse, the protagonist initially clearly lags behind her colleagues in terms of cleaning up the facility. She’s slower, clumsier, and less resourceful. But the longer she has to rely solely on herself, the more confident she becomes. She not only works faster but also takes initiative and responsibility for herself and others. Ultimately, Chihiro resolves a serious crisis caused by the appearance of the foul-smelling, sludge-covered deity. She is the one who saves everyone from being devoured by No-Face, and she’s the one who starts making decisions about the course of often dangerous events. Chihiro ceases to be a fearful ten-year-old girl hiding behind her mother’s skirt – she becomes an independent, responsible, and growing young woman who won’t be frightened by sticking her hand into the sharp-toothed mouth of an injured dragon, not to mention moving to a new home.

Coming of age story

So, Spirited Away is a coming-of-age film, as Anglo-Saxons and the rest of the film world like to call it, but it’s very specific, filled to the brim with wonders that only an outstanding artist like Hayao Miyazaki can conjure. His film is just bursting with life and unbridled creativity in every minute, drawing deeply from Japanese folklore and culture. Humanoid frogs in bathrobes working as servants in the bathhouse are just the tip of the iceberg that you simply have to see with your own eyes. Tiny creatures covered in soot carrying coal to the boiler room, three hopping, green-faced heads with mustaches, a gigantic baby, a parade of various kami in different shapes, sizes, and colors, the shape-shifting witch Yubaba ruling over the entire bathhouse—these are just a few of the fantastic creations brought to life by Miyazaki. Sometimes, it’s hard to pinpoint the exact element of native folklore that the director is drawing from, but Spirited Away overflows with layers of meanings, symbols, and references that are clear only to the Japanese or those well-versed in their culture. However, the strength of the film lies in the fact that even without knowing all these references, a viewer from any corner of the globe can easily understand the story and get lost in this enchanting, colorful world, where discovering each new wonder is thrilling in practically every scene.

Following this narrative and audiovisual mishmash is made even more enjoyable because Miyazaki ensured that his characters are not only intriguing and different from everything we know but also likable and at the same time ambiguous. Almost every character initially seems full of flaws, irritating, or curt, but over time, it becomes clear that they are all just authentic (which might sound especially paradoxical in the context of such a film). Authentic because they are neither entirely good nor entirely bad, neither overly strong nor too weak. They just don’t always make the right decisions. Even the theoretical villains are not entirely evil and sometimes simply arouse genuine sympathy and attachment. While accompanying Chihiro on her journey, we observe a whole palette of colorful (both literally and figuratively) individuals, and at the same time, we wholeheartedly cheer for this endearing, slightly awkward but incredibly determined ten-year-old in her daring endeavors.

Miyazaki keeps viewers engaged throughout the two-hour duration of Spirited Away, offering no moments of respite in the company of anything familiar, fully understandable, or ordinary. Here, every scene, every sequence unveils new elements of this incredibly complex yet fascinating world – the rules that govern it, the characters who inhabit it, and the relationships between events. What’s characteristic of Miyazaki’s work and so captivating when you closely examine Spirited Away is the completeness of this reality. Miyazaki allows you to look where you wouldn’t normally look and discover genuine life – and it’s not just about the phenomenal attention to detail in the set design. For example, when Chihiro is riding a train – theoretically at the center of the viewer’s attention – the tiny characters accompanying her are busy with their own affairs, getting excited about the scenery outside. And when Chihiro’s foot gets in the way of the little coal-carrying creatures, you can see their irritation when they can’t bypass the girl. This space within the frame, which most filmmakers are reluctant to occupy, always shows Miyazaki’s love for the worlds he creates; he wants them to be simply alive.

Consumerism

And if a story with a moral, combined with an incredible world, unforgettable characters, and a powerful dose of artistic expression weren’t enough, Miyazaki adds additional layers of meaning to Spirited Away, which are discovered with each subsequent viewing of this masterpiece. Because it’s not just a coming-of-age story, about maturing into a new life situation and learning responsibility for oneself and others. This film is also a clear critique – not the first in Miyazaki’s career – of consumer society blindly fixated on capitalism, obsessed with money, and disconnected from spirituality or tradition. Chihiro’s parents turn into two greedy pigs after voraciously devouring excessive amounts of food not meant for them – her father justifies his gluttony by saying that when the restaurant owner returns, he’ll have cash and credit cards ready. This is perhaps the most vivid metaphor for rampant consumerism, but not the only one.

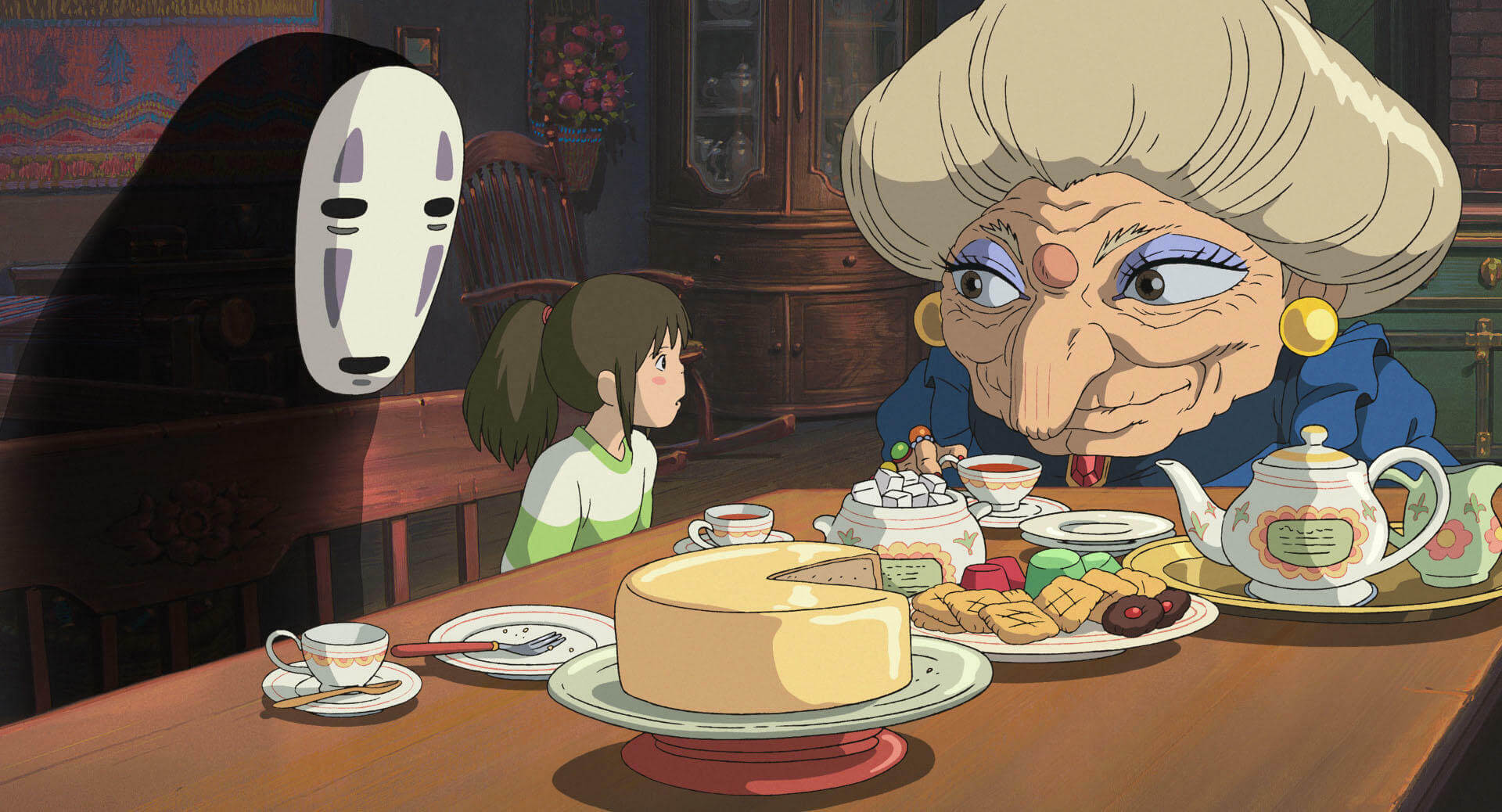

Evidence is also provided by the appearance of the No-Face in the bathhouse. Although it was clear from the beginning how important profits were to the ruler of the bathhouse, Yubaba, and her subordinates, even at the expense of the well-being of the lowest-ranking workers in the capitalist hierarchy. However, the arrival of the mysterious No-Face highlights their greed for money. When it turns out that the No-Face can create pure gold out of thin air, it becomes an undisputed VIP. The bathhouse staff throws parades in his honor, begging shamelessly for even a tiny gold nugget. The price for greed, however, is high. The No-Face devours the greedy servants one after another, and its anger destroys everything in its path, including almost all of the bathhouse’s food supply.

The No-Face is also an interesting example of how a negative environment can have a destructive influence on an individual. Although at one point it devours the bathhouse’s servants alive and becomes a huge threat, it is not inherently evil. It is a faceless entity, devoid of characteristics, easily influenced by its surroundings and imitating others. When it sees that money or simply possessing certain things is necessary for gaining benefits, it does the same thing – on an extreme scale. Chihiro’s words are significant: “He is only bad in the bathhouse.” When the No-Face is fed by Chihiro with a cleansing dumpling and then goes to the house of Zeniba, Yubaba’s benevolent twin sister, it begins to engage in useful tasks, teaching patience and humility through handicrafts.

Metaphor

The magical but chaotic world that Chihiro enters can also be interpreted as another metaphor, one that recurs in Miyazaki’s works both before and after this film. It’s a metaphor for Japan, a nation that has forgotten its roots, replaced by a pursuit of modernity, greed, and an obsession with Western trends. The bathhouse, although designed in a traditional Japanese style and ostensibly meant for the care of legendary deities, is, in reality, a place solely focused on profits. The rooms and clothing of the bathhouse’s ruler, Yubaba, are maintained in a distinctly Western aesthetic. Yubaba also takes away Chihiro’s real name, and the girl must ensure not to forget it; otherwise, she would become a rootless and identity-less part of the consumerist machinery.

However, it’s not a matter of clinging to the past while rejecting the present. Ultimately, Chihiro feels most comfortable in her contemporary times and way of thinking. The magical world itself is not without flaws. Miyazaki seems to be conveying the importance of coexistence, something vital to his ancestors but lost to younger generations. Chihiro establishes, or rather renews, a connection with tradition, accepting it and bringing order to chaos, but in the end, she returns to the contemporary world where forgotten kami shrines are scattered on the roadside, and parents travel in German Audis. Chihiro, however, is transformed, symbolized by the sparkling hair tie she received as a farewell gift from her magical friends from another world.

Ecology

Chihiro also lives in a world where concern for the natural environment is increasingly losing its significance. In Miyazaki’s works, ecology always holds a particularly important place, and although it is not as prominent in Spirited Away as in his most environmentally conscious films like Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) or Princess Mononoke, it has a significant influence on Chihiro’s restoration of order in the bathhouse. Miyazaki introduces environmental themes primarily through two characters.

The first character is a deity who arrives at the bathhouse in the form of a foul-smelling, sludge-covered monster. The appearance of this creature, which dirties everything around it, poses a significant problem for Yubaba and the other employees. However, it is Chihiro who realizes that something is amiss. Moments later, she extracts a bicycle and a slew of other items, including home appliances, scrap, and fishing accessories, from the slippery body of the creature. In essence, it’s all the things that people mindlessly discarded into the water—because the Stink Spirit turns out to be the River Spirit, brought to a pitiable state by humans. Only Chihiro, wanting to help rather than profit from it, is able to free the spirit.

The second character in Spirited Away who relates to environmental issues is Haku, a young man who is Yubaba’s right-hand man but is, in reality, her prisoner. Later in the film, Chihiro realizes that she had encountered the mysterious boy before—as a small child, she had fallen into a river, but the river safely deposited her on the shore. That river was, in fact, Haku, another river deity who, due to Yubaba, has forgotten his identity and become her captive. When you add Chihiro’s statement that the river in her world has been drained and turned into a housing development, the interpretation of the relationship between the captive Haku and the greedy Yubaba becomes quite apparent.

Is that all Spirited Away has to offer? Absolutely not, as each subsequent viewing allows for the discovery of new meanings, different for each viewer. Some may see, for example, a metaphor for the sexual exploitation of minors, while others analyze the symbolic significance of the Japanese restaurant names passed by Chihiro and her parents at the beginning of the film. What is certain is that Spirited Away is a showcase of true cinematic artistry, unrestricted by either imagination or production constraints. It is filmmaking in its purest form, captivating both connoisseurs and regular viewers. Moving, filled with ambiguous, likable, unforgettable characters, visually stunning, symbolically multi-dimensional, and narratively impeccable – simply excellent in every detail.