Masterpiece or harmful trash? What’s up with “Emilia Pérez”?

Let’s go back in time by nine months. It’s mid-May 2024. On the French Riviera, the annual Cannes Film Festival is coming to an end. One of the most enthusiastically received films is the latest work by Jacques Audiard, a favorite of the French public—Emilia Pérez. This wild musical about transition, set in the world of Mexican drug cartels, is competing in the main competition, and behind the scenes, it’s being touted as a frontrunner for the Palme d’Or. Ultimately, however, the festival’s top prize goes to Sean Baker, the director of Anora. But Emilia Pérez does not go home empty-handed—Audiard’s film receives the Jury Prize and the Best Actress Award, shared by Zoe Saldaña, Karla Sofía Gascón, Adriana Paz, and Selena Gomez.

Even during the Cannes festival, a bidding war erupts over the distribution rights to the musical, eventually won by Netflix. When the film hits American theaters in November—followed shortly by its release on the streaming platform—an event occurs that no one in their right mind could have predicted: Emilia Pérez, hailed as a postmodern masterpiece in Europe, is met in the United States with overwhelmingly negative reviews and audience hostility. At present, its user rating on Rotten Tomatoes stands at a staggering 17 percent. Why?

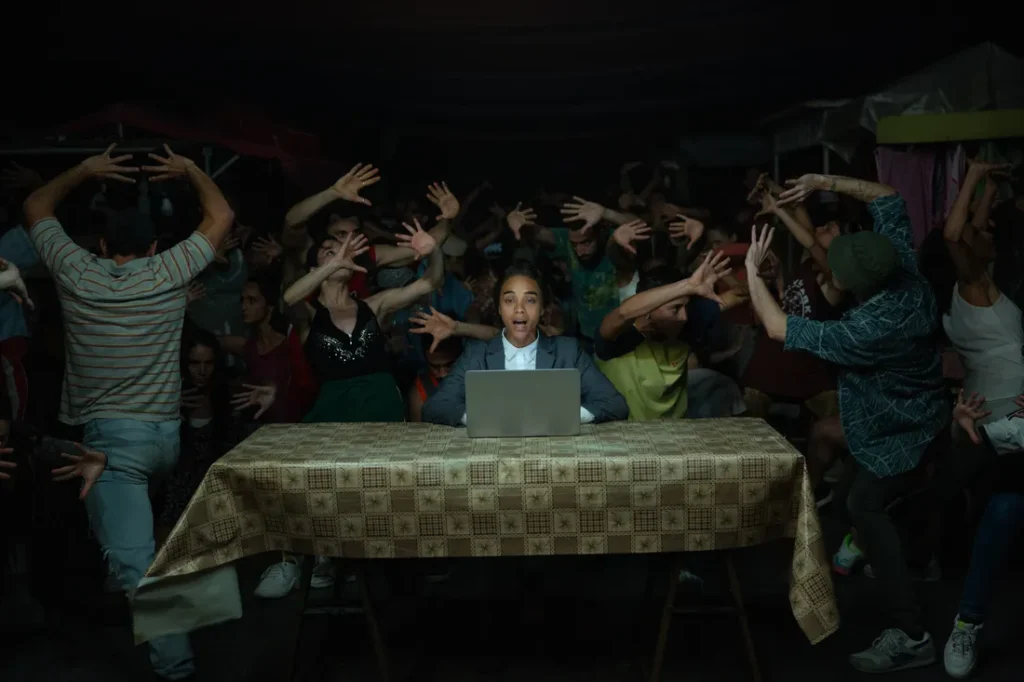

In an increasingly polarized U.S., Audiard’s film is being attacked from both sides. Some see it as the epitome of “utter woke nonsense,” while others criticize it for its false progressiveness. As one might expect, the arguments of the latter group are far more interesting—and certainly more reasonable. To understand them, all you need to do is watch one of the countless loud YouTube videos with clickbait titles and exaggerated thumbnails, such as “The Biggest Villain of This Year’s Oscars,” “Everything Wrong with Modern Hollywood,” or “The Worst Film with 13 Oscar Nominations.” The same accusations appear in all of them: stereotypical portrayals of Mexico, harmful representation of transgender people, an unlikable protagonist, and bad songs (with the delightfully kitschy La Vaginoplastica leading the way).

There’s no arguing with the facts: Audiard has made a film set in Mexico, but in Europe. Although he initially planned to shoot on location, he ultimately opted—purely for logistical reasons—to use the Studio de Bry near Paris. He worked primarily with his trusted French crew, and for the main roles, he cast not native Mexicans, but a Spaniard (Gascón) and two Americans—one of Dominican descent (Saldaña, who speaks Spanish fluently) and the other of Mexican descent (Gomez, whose Spanish skills are reportedly quite poor). In short, authenticity was not a priority. On top of that, he touched a nerve with Mexican audiences by centering his film on the subject of drug wars—a still unresolved and highly controversial issue that modern pop culture frequently exploits.

As for the criticism regarding the transition storyline, the arguments echo a similar theme: Audiard, as a cisgender, heterosexual man, is accused of speaking on subjects he has no real understanding of. That the transformation of Manitas into Emilia is magical and unrealistic. That, along with her body, the character’s entire personality changes—from a ruthless cartel boss to a benevolent philanthropist—thus undermining the very nature of gender transition. Fueling this type of criticism are Audiard’s own remarks, in which he candidly admits that before making Emilia Pérez, he felt no need to deeply research either Mexican history or the experiences of transgender individuals. “I already knew everything I needed to make the film,” he stated with disarming honesty in one interview.

Allow me to play, for a moment, the role of Rita Moreno’s character, portrayed by Saldaña in the film—a female counterpart to the devil’s advocate. Because as ignorant, Eurocentric, and frankly unfortunate as Audiard’s statement may sound, I actually believe he has a point: making Emilia Pérez truly didn’t require him to have expert knowledge of either Mexican history or the transition process. For one very simple reason—the film never claims to be a serious commentary on either of these topics. Both are sacrificed at the altar of audiovisual spectacle—a lavish, genre-blending hybrid where, alongside musical and gangster film elements, the key word in any discussion about Emilia Pérez should be: telenovela.

Exaggerated, shamelessly kitschy, and emotionally extreme—the telenovela became deeply embedded in the minds of Polish audiences in the mid-1980s when the country unexpectedly experienced a boom thanks to Isaura: The Slave Girl. Legend has it that during its broadcast, the streets of Polish cities would empty as everyone gathered around their TV sets to follow the fate of their favorite characters. Although this hit show originated in Brazil, today, Mexico is the leading exporter of such productions. As the demand for telenovelas grew, their traditional themes—taboo love, family conflicts—began incorporating what we might call social issues. Class divisions, corruption, immigration, and drug trafficking all made their way onto screens—though always treated primarily as dramatic plot hooks to keep viewers engaged. Suffice it to say that one of the most popular Spanish-language telenovelas in recent years has been Queen of the South—a story about a woman who, seeking revenge for her husband’s murder, establishes her own drug cartel. And after the massive success of its first season, who do you think acquired the rights to distribute the series? What a surprise—Netflix.

I bring all this up because Emilia Pérez fully embraces this specific convention. The entire melodramatic storyline feels as if it was lifted straight from a nonexistent Latin American telenovela—a drug lord fakes his own death to undergo transition and sever ties with his family, but after the operation, he begins to miss them. So, he brings them to him and plays Aunt Emilia for them every day. Does it sound absurd and unrealistic? Good—it should sound that way. That’s why I find analyses pointing out the film’s implausibilities (such as the one by the YouTuber Bez schematu) amusing. If someone expected Audiard’s musical to be a work of gritty social realism, they were simply looking in the wrong place. The Dardenne brothers live two streets over.

The telenovela aesthetic also embraces broad stylization (which is characteristic of musicals as well), and Emilia Pérez follows suit. The setting, which has caused the film so many enemies, is deliberately stylized. As Katarzyna Czajka-Kominiarczuk noted in a discussion with Łukasz Stelmach, this is not a film about Mexico but a film about a vision of Mexico—a telenovela vision, exaggerated, steeped in stereotypes that are commonly perpetuated in productions like Queen of the South. Emilia Pérez repeats them too, but its genre at least partially justifies this choice.

The transition storyline is also highly stylized—on the surface, it feels more like a spiritual transformation than a physical one, akin to the biblical story of Saul’s conversion. The deadly gangster undergoes gender correction and becomes the complete opposite of his former self—a modern-day saint, helping families find loved ones kidnapped and murdered by cartels. But is that really the case?

One of the main accusations leveled against Emilia Pérez—as pointed out by Bez schematu—is the protagonist’s unlikability, evident in her controlling behavior, deceit, and manipulations even after her “transformation.” But in criticizing the character’s construction, the reviewer unknowingly highlights one of the film’s greatest strengths: Emilia Pérez is psychologically complex. Yes, she changes her actions, dedicating herself to helping those she once harmed. But at the same time, she wounds her loved ones, driven by pure self-interest. In the end, Emilia fails spectacularly. Her misguided choices deprive her own children of both a father and a mother.

Finally, let’s talk about the music. American commentators love to trash the songs: weird, clunky, embarrassing, absurd. But Emilia Pérez is not a traditional musical—it doesn’t stem from Broadway tradition but from European art cinema, like the colorful musicals of Jacques Demy.

If the bizarre reception of Emilia Pérez proves anything, it’s the power of broader discourse (in this case, American) to shape individual perceptions of cultural texts.