Discussing urban legends with Joshua Zeman, director of CROPSEY

Which came first, the phoenix or the flame?

A circle has no beginning.

An urban legend. A story passed along verbally, getting more and more detailed, and having those details constantly altered while one thing remains unchanged – a message, often chilling to the bone, which sets fire to emotions, with a mandatory reference that it happened to my sister-in-law’s colleague or my cousin’s sister’s grandma.

We had a few of our own in Poland. The most famous one tells a story of a black Volga with curtains in its windows – allegedly it was seen cruising the streets and waiting for new innocent kids. Behind the wheel – insidious Germans dressed as priests and nuns. Sometimes the Security Service (SB). Sometimes Jews…

Related:

Cropsey

Water tattoos distributed in front of primary schools, filled with LSD. A row of dots as the answer to the secondary school final exam’s question: “What is risk?” Wisława Szymborska who failed to interpret her own poem. A “Mission to Mars” cardboard box with a student inside, launched through a dormitory’s window. A famous couple of drug addicts who roasted their baby in a microwave oven, a wedding outfit soaked with cadaveric poison. Some urban legends are absolutely ludicrous, while other show some level of probability. What is their role?

How are they created? Is there a kernel of truth in them? What came first: a legend or a fact? Or maybe an emotion, most often fear?

According to sociologists, urban legends are born in moments of crises or breakthroughs. They are a natural defense reaction of a society trying to tame what is unknown and unsure, or sometimes give a warning in a horror form which stimulates imagination. What influences the content of urban legends? What fuels them?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NYskVg6Ea9A

This question provided a common ground for me and Josh Zeman, the director behind two interesting documentary films taking up the topic of urban legends: “Cropsey” and “Killer Legends”. I have already mentioned “Cropsey” in my list of 12 noteworthy crime documentaries. Still, there is no harm in digging a little deeper, especially when the author of both scripts is at your disposal. We truly delved into the topic of urban legends. Ultimately, we came to certain conclusions and formulated a couple of theories – but how adequate are they?

“I feel that the genesis of urban legends is essentially intuitive. You will agree with me that we, as a species, are driven by fear. We’re not sure what can make us happy but we know precisely what chills our blood, don’t we? Our basic instinct tells us to survive, no matter what. We don’t enter a dark cave because inside we might face a bear. We don’t wander off a safe camp because there might be lions around. We may be over-dramatic when we wish to caution others. An urban legend evokes fear, but it also makes it visual. It is an integral part of the evolution of the species,” explains Josh.

Podobne wpisy

I am asking how it was in his case. Growing up in Poland, I was repeatedly warned about kidnappers’ black car, as well as drug dealers. Josh, a few years older than me, spent his childhood on Staten Island and used to be spooked by Cropsey. It was on a school camp when he heard about him for the first time. The story blended in with the neighborhood he grew up in: the forests which served as meeting places for the homeless, the abandoned mental asylum, the tuberculosis sanatorium, also falling to ruin. Kids used to scare one another like crazy with this image of an unstable patient who hunted for unwary youth venturing into unfriendly places. A dangerous and unpredictable psycho: Cropsey. A myth, a symbol, or maybe something more?

“We don’t have to fear bears or lions anymore. There are dangers of a different sort, though. You can see it by looking at the content of popular urban legends: organ theft, intentional infection, serial killers, sects. Everything that can hit our kids and, at the same time, menace the survival of the species. We feel permanently insecure about the future of our civilization.”

“But these concerns are well-grounded,” I remark. “There are murderers, there are sects, as well as much more mundane dangers. It’s difficult to detract teenagers, bubbling up with hormones, from a little hanky-panky in a love lane – and each city has one – but it’s easy to scare them with a vision of a killer with a hook instead of a hand. The symbol makes more impact than the story itself. A slayer with a hook is a more frightening possibility than the Son of Sam, yet David Berkowitz hunted couples in love for real, and he also killed them for real, while a psycho with a hook is a local legend. The Son of Sam was captured, thus made harmless, but the Hook will live forever. It’s not even about warning somebody that if you go on a pleasurable date, you may be attacked by a masked avenger. It’s about making you NOT go on such a date, just like that. Because careless sex may result in unintended pregnancy. Because a nice guy from your neighborhood may not take “no” for an answer. Because your loved ones can’t protect you from everything that scares them, but they truly want to save you from pain and disappointment.”

“This mechanism would be quite clear,” retorts Josh, “if it wasn’t for a tiny detail. We just looooove to be afraid. Nothing gives more thrill than a scary story. And it’s a short way from fear to sex. Taking a girl to a haunted house and scaring her to death with some ghost story makes for a surefire method of getting her into your manly loving arms.”

What a chauvinist, son of a gun! But what can I do – he’s right. Urban legend is unquestionably a double-edged sword. But then again, what happens when there’s some truth in it? Cropsey is a symbol, of course, a universal one that could easily appear in any country, in any culture. For instance, Leszek Pękalski, a disturbed man from Poland, was quite successful in hunting naïve female hitchhikers and unaccompanied women in dark walkways. What’s worse – he’s about to be on the loose again in a year. That’s our own private Cropsey.

According to Josh, on Staten Island one of many faces Cropsey had was Andre Rand.

Josh and his co-director Barbara did not manage to reach out to Rand who is currently in prison. He is serving his sentence for kidnapping, as it was impossible to connect him with any murders. Nevertheless, it is not just a local story but a sad truth that during his time on Staten Island many children went missing. Starting with Alice Pereira in 1972 and ending with Jennifer Schweiger in 1987 – children were vanishing, as if they had really been kidnapped by a nameless boogeyman. Suddenly, Cropsey turned out to be real, while Rand’s archival photos whipped up mass hysteria – with his fishy eyes and foam coming from his mouth he epitomized the notion of a madman.

“Urban legend springs from uncertainty,” says Josh. “Something may have not happened but it well may have. Rand’s case fuelled the Cropsey legend, it added the element of probability, even if the legend itself was a combination of various stories strengthened throughout years. Campers murdered in their tents. Mental patients on the loose. Devil worshippers performing dark rituals in forests.”

“We filter urban legend through our own beliefs and fears. Because it’s impossible to easily determine who’s guilty and why. For some people Cropsey will function as a warning for society with deeply biased attitude towards the mentally ill. For others, especially parents, a warning of a pedophile offering candies. Religious fanatics will in turn look for connections with the devil,” says Joshua. “Being a director, that’s what I find most fascinating.”

The people whom he and Barbara met while shooting “Cropsey” inspired Joshua to investigate the matter further. Roaming the ruins of the Staten Island hospital’s flank, they kept bumping into groups of teenagers fascinated with the story and eager to share all rumors they heard… from an eyewitness, of course. I guess it’s unnecessary to mention that each of those teens said something different.

Killer Legends

In the next project, “Killer Legends,” Joshua and Rachel Mills went a bit further and worked with some of the most popular urban legends in the USA. They asked what came first – the egg or the chicken? The phoenix or the flame? The legend or its factual foundation? They were soon to find out that a circle truly has no beginning. How many times have you seen in films the same old story of a murderer with a hook instead of a hand, who awaits a couple in love in a parked car. Sometimes it’s a couple on a date, the girl hears a suspicious sound and sends the guy to check what it was. Sometimes it’s newly-weds on their honeymoon, spooking each other with stories of a boogeyman, then the wife wakes up in the morning to a screeching sound resembling a hook scratching on a car body… What it really is, though, is the screeching wedding ring on the inert hand of her murdered husband, whose body was hanged on a tree just above the car. And sometimes it’s teenagers dispersing in panic into a forest, while the called police finds a hook stuck in a car’s door. Versions are aplenty, but they all have one thing in common – isolation, a couple having sex, punished for their need for privacy, and the elusiveness of the faceless killer.

A story as old as lovers in secluded lanes. Nevertheless, is it reflected in reality? Joshua took his camera and travelled to Texarkana, to look closely at the Phantom story, by no means legendary and 100% real, although it has become a myth since the time of the actual events. Today it’s difficult to clearly separate facts from fiction. The legend became larger than life, while life gave rise to another legend. The circle keeps turning. The homicidal fugitive from Texarkana didn’t have a hook, but he did have a gun and he used its barrel to rape one of his victims. According to a sociologist Joshua had a chance to speak to, a gun as a brutal extension of a hand works as an equivalent of a hook from the urban legend.

The masked Phantom Killer who keeps slipping away. The Zodiac Killer, also masked and elusive. More of a symbol than anything else. A symbol created rather deliberately. Doesn’t the Zodiac Killer story make for a great urban legend? And what about the so-called Tylenol Murders? Somebody added potassium cyanide to some random batch of a popular painkiller which resulted in seven deaths. May sound as a legend but it did happen.

“That’s why you can neither deny nor confirm an urban legend. There are more things possible than we can imagine. That’s where the power of such stories come from,” says Joshua.

“With your American obsession with Halloween, creating a Halloween legend was just a matter of time,” I said, referring to the second story included in the film, the one about Candyman. “But again, there are two sides to it,” retorts Joshua. “Maybe even more than two. Look – we’re dealing here with a situation when a legend is supposed to warn kids about strangers offering treats; with a real incident when a little boy dies after eating a poisoned candy and his father is charged for this crime; and with a whole nation blaming this father (who pleaded “Not Guilty” until his very last moment when he was executed) that – this will be interesting – he ruined Halloween for everybody because people won’t feel safe anymore. One swallow doesn’t make a summer, though, and one such case doesn’t make a common trend. But it can lay the groundwork for manipulation and that’s another face to urban legend we have to deal with. There’s no easy way here.”

“Nothing gives me greater pleasure than debunking the allegedly true basis of an urban legend. Because, in fact, many of them were created in order to control us, arouse in us fear of what is foreign and obscure. Like immigrants, homosexuals, or Jews. This is manipulation, so effective in its ways that it poses a substantial obstacle in our own search for the truth.”

“There’s nothing strange in it,” I remark, and we both settle on one thing: the truth can be ugly, it can be tough, it can be difficult to accept and embrace, it may require a complicated intellectual analysis. But a legend? Well…

“Plain, lightweight and witty. Reducing a complicated process of intellectualization to a simple and easily definable category,” says Josh while nodding his head.

And what about the story of a babysitter harassed on the phone by an intrusive stranger and then informed by the police that the hoaxer is hiding somewhere inside the house? There were murders like that. It doesn’t mean, though, that working as a babysitter puts you necessarily in danger, as if that was a high-risk profession. Rather the contrary. Almost each teenage girl in the USA babysat somebody’s kid at least once in her youth. A single tragic accident – although sad and upsetting – remains just an isolated case. So what makes a basis for the legend itself? Again, it’s a warning about being irresponsible and carefree. “Have you checked the children?” – asks an anonymous voice on the other end of a telephone line. Ergo: you have responsibilities, a task to fulfill, bear it in mind before you let your boyfriend in through the back door, or start gabbing on the phone with your bestie for hours. The legend shouldn’t be understood literally, it doesn’t mean there’s a global threat for all babysitters who automatically become objects of interest for killers. It should be understood symbolically, even if there’s a reported case of a babysitter who got killed.

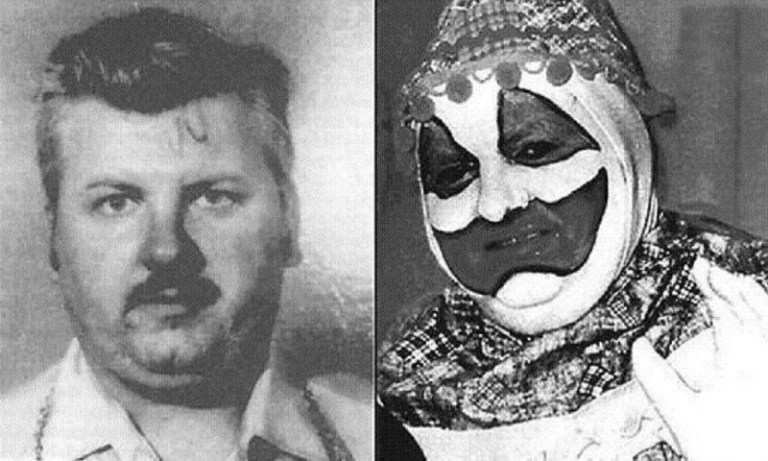

Symbols are more expressive than facts. While everyone in Chicago knows who John Wayne Gacy was and what was his modus operandi, it doesn’t mean the same story repeated, let’s say, in China, would have the same poignancy. And that’s where this tendency to make it more realistic come from.

“If you want to scare to death somebody from Russia, the Gacy story won’t work. So you say: this happened to somebody I know. And that’s how your story makes more impact,” says Josh.

But who needs Gacy? If you want to scare me stiff, just mention a clown. They freak me out, what can I do? Probably because of “It” and Pennywise, but Josh, a few years older than I am, owes his phobia to “Poltergeist.” Nevertheless, we agreed that for us there’s nothing mythically hilarious about clowns. How can you deal with a clown anyway? They are principally devious. You cannot know what’s behind that painted, impersonal smile. It can be anything but still a clown pretends to be so cheerful, easy-going and funny. You just don’t know how to approach it.

There’s one more aspect of our fear of clowns expressed in the form of an urban legend – we have probably managed to get used to this ambiguity, haven’t we? I’m talking about our fear of insincerity. We all put on masks so we automatically assume that this must be the case with the people we meet. We are afraid of being manipulated, and, as a result, making a fool out of ourselves and getting hurt. At the beginning all seems so cool and joyful but in the end the best we can hope for is laughter through tears. The killer clown legend doesn’t have to warn about Gacy. It can simply draw our attention to the fact that carelessness should be alarming.

Josh, now busy splitting his attention between a project on “the loneliest whale in the world” and the Long Island serial killer case, tries to sum it all up by defining himself.

“I like to scare people. But I also wish they asked themselves what terrifies them and why. It’s not about this one-second fear when somebody suddenly jumps at us from behind a tree. I want to know why people are scared of clowns, why so many of them are eager to believe that there’s someone ready to poison sweets for their kids. I’m fascinated with the secrets of narration and its never-ending evolution. Narration understood as storytelling, some sort of continuity, when a book inspires a film, and a legends inspires a book. The foundation of such narration seems very simple, yet it is in fact surprisingly complex. And, interestingly enough, even if we conduct a meticulous analysis of it – it will still have the power to spook us.”

Translation: Katarzyna Kuźma